Taking on TB: Jillian Landeck in Tajikistan

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

“A lot of the interviews, especially with stigmatized women, were really tear-filled,” Jillian Landeck recalled. “It was hard, emotional work.”

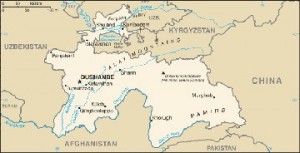

Landeck, a second year student at the University of Wisconsin – Madison School of Medicine, spent six weeks in Tajikistan (tuh-GEE-kuh-stan) earlier this summer with classmate Erin Peck serving with the US Agency for International Development (USAID) as short-term consultants. Their task was to create and conduct a survey that would help determine the quality of health care received by patients with multi-drug resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB).

Jillian Landeck’s travels to study drug resistant strains of tuberculosis took her to Iskanderkul, a glacial lake in central Tajikistan.

Funded by a grant from Zorba Paster (of National Public Radio’s On Your Health), the two women traveled from mid-May to July 1 throughout Tajikistan – the poorest of the former Soviet Union countries – interviewing 50 patients and 15 healthcare providers. The purpose of the survey was to determine the effectiveness of the healthcare project that had begun in 2009.

While tuberculosis, a bacterial disease that usually affects the lungs, has largely been eradicated in the United States, the World Health Organization estimates that as much as a third of the world’s population are carriers for the disease. During the past 10 to 15 years, multi-drug resistant strains of TB have emerged. While classic tuberculosis requires a six-month course of treatment with antibiotics, MDR-TB requires a two-year regimen.

Because tuberculosis pathogens are airborne, healthy people in the country tend to avoid those who are ill. From her interviews, she got a clearer picture of how the stigma attached to a disease impacts people’s personal lives and relationships.

“The most compelling evidence came from talking to patients, especially in smaller villages,” Landeck said. She found the plight of married women with the disease especially poignant.

“Women don’t have many rights, even though they are the heads of their households,” she said. “Marriages are often arranged, and [the women] work incredibly hard. We talked to several women who had been diagnosed and abandoned by their families,” a situation devastating both emotionally and economically.

In addition to the discrimination faced by those affected by tuberculosis, the questions on the survey that addressed accessing and complying with treatment revealed that people also suffered from a lack of understanding about the disease itself. Especially serious, she noted, are the geographic and economic barriers to treatment.

“Transportation was a major issue,” she said, “as people had to walk miles to a clinic.”

Because the course of treatment extends over a two-year period, patients sometimes feel that they cannot afford to continue it. “One-half of all working age Tajik males migrate to Russia and Kazakhstan to find work,” Landeck said. “Once they quit treatment they are at risk for developing drug-resistant TB.”

At times the experience was frustrating for her. “What can I do, a second year medical student?” she thought, well aware of her limited skills and resources. But she found working with the people a rewarding experience.

The country, which borders Afghanistan to the south and China to the east, is mountainous with only 6 percent of the land arable, and the population faces problems with food, drinking water, healthcare, education, and infrastructure.

Jillian Landeck (foreground) and other members of the survey team conducted a number of interviews throughout the country of Tajikistan at rural clinics similar to this one.

“But I found the people to be extremely gracious,” she said. When she’d travel to a remote area, they “always greeted me with smiles, laughter, and enthusiasm. When we’d sit down to interview them, other family members would bring food and tea, bake bread, sometimes slaughter a goat or sheep – you knew they brought almost all of their food to share. It was so humbling.”

She enjoyed going to a place where few Americans have traveled and found it a beautiful part of the world, with mountains and glacial lakes. “I felt very safe,” she said, laughing that she sometimes felt safer in Dushanbe (the capital city) than she sometimes has in Madison.

Landeck hopes to begin her residency as a primary care physician in 2014, and would like to have a practice in a small town, much like her hometown of Sister Bay. She enjoys working directly with patients (she has had experience in free clinics), but she also enjoys travel (her studies have also taken her to Peru, Chile, Ghana, and Indonesia).

Now home from Tajikistan, Landeck is serving a clinical preceptorship with Dr. Phil Arnold at North Shore Medical Clinic in Fish Creek before she returns to UW – Madison this fall to continue her studies.

Ways to Get Involved

Project Hope (www.projecthope.org) and the International Organization for Migration (www.iom.int) offer opportunities for concerned individuals to aid MDR-TB in Tajikistan.