Ten Key Questions for Candidates in 2018 State Elections: Part 5, Fiscal Health

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

On Nov. 6, voters will select Wisconsin’s governor, all 99 members of the state Assembly, and 17 of the 33 members of the state Senate. To help voters sort through the noise, we have identified 10 questions that candidates should be addressing regarding six key issues facing the state: transportation, economy and workforce, education, state-local relations, taxes, and Wisconsin’s fiscal health.

STATE FISCAL HEALTH

In terms of its fiscal health, Wisconsin’s condition can be divided into short- and long-term prospects.

As defined in research by the Mercatus Center at George Mason University, short-term health refers to the state’s ability to pay its bills as they come due, such as within the first 60 days of the fiscal year. These measures typically reflect the state’s bank accounts, liquid investments, and accounts receivable.

Wisconsin’s short-term health has improved since 2002-09. During that period, the state depleted its unemployment compensation (UC) reserves and struggled with declining income and sales tax collections due to the 2001 downturn and, later, the Great Recession. While the state has rebuilt its UC fund and income and sales tax collections have largely recovered, it still ranks 38th among states for short-term financial stability.

Wisconsin’s short-term health has improved since 2002-09. During that period, the state depleted its unemployment compensation (UC) reserves and struggled with declining income and sales tax collections due to the 2001 downturn and, later, the Great Recession. While the state has rebuilt its UC fund and income and sales tax collections have largely recovered, it still ranks 38th among states for short-term financial stability.

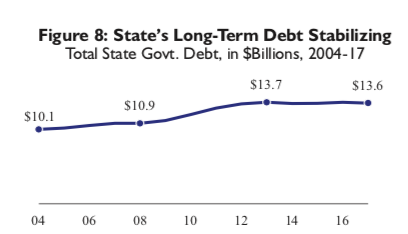

Long-term health considers the state’s debt load and other outstanding obligations. These can be measured in terms of per capita obligations, liabilities relative to assets, and net assets to total assets. Our February report noted that Wisconsin ranks 27th nationally on combined measures of long-term fiscal health.

Overall, the state has stabilized its use of long-term borrowing, particularly for transportation projects, which had been increasing an average of 3.5 percent annually from 2004 to 2013.

Wisconsin has traditionally avoided one potential threat to long-term financial stability: unfunded pension and post-retirement employee benefit liabilities. Unlike other states, Wisconsin’s pension system is fully funded, as are its obligations for post-retirement health care benefits for employees.

Wisconsin has also taken steps to improve its “rainy day fund” and other budget reserves to safeguard against economic downturns.

Between 2002 and 2011, the state typically had a combination of ending balances and rainy day funds of less than one percent of spending; in fact, it rated the second worst prepared state for the 2007-09 recession, behind only Arkansas.

Between 2002 and 2011, the state typically had a combination of ending balances and rainy day funds of less than one percent of spending; in fact, it rated the second worst prepared state for the 2007-09 recession, behind only Arkansas.

The state ended 2017 with a positive general fund balance of $579 million, plus an additional $283 million in the rainy day fund, for a total reserve of $862 million, or roughly 5 percent of general fund spending.

Although that figure represents a substantial increase over past levels, 35 states had larger savings in 2017 than Wisconsin; nationwide, states had a median reserve of 8.9 percent, according to a survey by the National Association of State Budget Officers.

By the end of the 2019 fiscal year, however, Wisconsin’s general fund balance is projected to decline to $181.6 million. Combined with an anticipated rainy day fund of $350 million, that would leave the state’s total reserves at about $531.6 million, or roughly 3 percent of general fund spending.

Question for candidates:

10) Although Wisconsin’s fund balance has improved in recent years, its reserves to weather financial downturns still remain behind many other states, a situation that leaves it vulnerable to higher-than-predicted costs or lower-than-expected revenue. What, if anything, would you do to even out this boom-or-bust budgeting cycle and build up the state’s reserves?