The Accidental Poet: A Q&A with Hal Prize poetry judge Mark Wunderlich

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

Though Mark Wunderlich calls the East Coast home, his poetry often conjures images of the Midwest he grew up in: the farms, the snow, the neighbors and the many other people and places that we who call it home are very familiar with. Within this setting, he tackles questions about life and death, the human condition, and God. He writes about the discoveries he makes tearing up a house, about a bat being a bat, about selling his family farm. His work is eloquent, humorous, haunting and captivating.

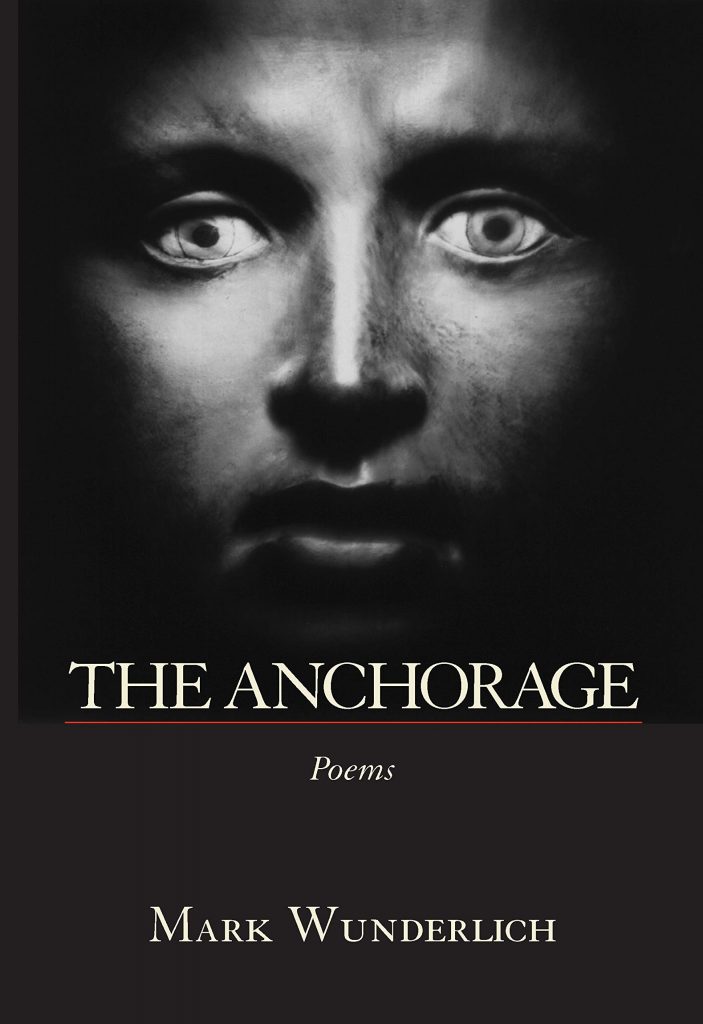

Wunderlich’s first book, The Anchorage, published in 1999, earned the Lambda Literary Award, and since then, he has received many prizes, fellowships and residencies. This past January, he published his fourth book of poetry, God of Nothingness. Wunderlich is an educator, reviewer, speaker and this year’s Hal Prize poetry judge.

We corresponded about his accidental path to poetry, the refuge he finds in a good poem and why publishing isn’t necessarily the great reward of writing that it appears to be.

Sally Collins (SC): You were born and raised in the Midwest, which appears often in your poetry: the nature, small farms and towns, and traditional Christian values that pervade this part of the country. I wonder whether poetry was an encouraged pursuit or something you felt pulled toward on your own?

Mark Wunderlich (MW): Your question is interesting to me, as it suggests that there might be people out there encouraging their children to pursue a life in poetry, which is hard for me to imagine, but anything is possible!

I was most definitely not encouraged to pursue writing as a vocation or a calling, but I wasn’t openly discouraged either. I don’t think it ever occurred to anyone that such a thing might be possible, or even remotely desirable. I don’t remember my family showing too much interest in how I would make a living, or make my way in the world, or what my larger ambitions might be, though I think they assumed – at best – I might be a veterinarian, but it was more likely that I’d end up as a farmer. They only wanted that I find a way to take care of myself, that I achieve independence, that I find my way in the world without too much involvement on their part.

I knew from a young age that I was interested in art and literature, but the place I’m from is notable as a part of the world in which art and culture has largely passed over.

I came to poetry on my own when I went to college, but my path there was indirect and accidental. I studied Germanic languages in college, attended an immersion program, wrote critical essays on literature and film in German, and I thought my life might be spent in Europe working for a government agency, or translating, as these were the only jobs I could see or imagine for myself.

At the university I attended, the military and U.S. intelligence organizations used to recruit language students – particularly those who spoke Russian and German – and I thought for some time that I might become, essentially, a spy.

Then I found myself in a poetry workshop quite by accident – and I felt my world shift. Thereafter, I began to read and write poetry with focused energy and attention, and here I am today.

SC: In an essay titled “Why I Write,” you wrote, “When I discovered poems and began to write them, it became clear to me that poems were objects, but ones with a minimal physical form; that they gave pleasure but they also irritated.” I love that. Can you expound upon the pleasure and irritation poetry brings?

MW: Very often the first poems we read are written for children, or are presented to children as sufficiently rudimentary that they might grasp them instinctually. Many of these poems rhyme or are metrical, and those patterns give us pleasure. Rhymes are, after all, quite comical and suggest relations between like-sounding words that lie somewhere beyond meaning and in the realm of the absurd, but there is something magical about this as well.

Everyone knows that charms and spells have to rhyme, and we learn that those memorable language patterns have a kind of power – at least in our imaginations. It’s fun to read poems like these (I’m thinking here of Lewis Carroll, perhaps), but those same poems are also often goofy, absurd, even nonsensical, and that which is nonsensical can also be irritating.

I remember being very young and reading from a bowdlerized version of Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and I was drawn to the man with a donkey’s head, and the existence of feuding fairy royalty, but I also didn’t really get what was happening or why, and this irritated me. How could this story be both completely magical and also so boring?

At this point in my life, I find reading to be one of the most reliable pleasures I experience, and I go back to favorite poems the way one visits an old friend. The poems I love are like rooms I can enter and move around in, full of the familiar furniture I have come to expect. These same poems also act as places I carry inside me, occupy, live in.

My favorite poems are those that retain mystery, that crack open an aspect of human experience whose bottom cannot be plumbed. These are the poems we reread, those that are ageless – eternal even – that transcend time, that open and open the world and expand our understanding of our human condition.

SC: I read that you are not a prolific writer – which is comforting as a writer who also works in fits and starts – so what is your process? How do you know when a poem is finished?

MW: I am actually a fairly disciplined writer, and I write every day. I don’t write poems every day, but I write something, and it’s usually first thing in the morning, before I attend to the day’s urgent responsibilities, whatever they may be. I have learned that by blocking out the first morning hours for my own work, I can face whatever else comes with a sense of early accomplishment. Having my own creative work be first is the best guarantee I have for contentment, for a sense of well-being and satisfaction. In this way, I am a very prolific writer.

What I don’t do much of is publish – or rather, I have never wanted to write something just to have it in print. I am not a great finisher of things, and I have loads of unfinished essays, poems, stories, translations and various other texts languishing with my best intentions still pinned to them.

Publication is such a mixed bag anyway. It’s not the great reward people mistake it for, but an entry into a conversation that will now go on with or without you, and the reward isn’t adulation, but participation.

The second part of your question is one that is asked often, but which will have to remain an unsolvable puzzle. One doesn’t really know when a poem is finished. I stop working on a poem when I feel I have cut away the fat, when the poem shows me something I didn’t know existed before I wrote it, or when I get bored with it, or when I think it’s not going to work, and then I put it on a heap to be salvaged for parts at some later date.

SC: Writing poetry is just a bit of what you do. You teach and have taught poetry at the undergrad and graduate level for many years. What joy do you derive from teaching? What do you hope students gain from your courses?

MW: Teaching has been my vocation for almost 30 years now. With undergraduates, I love helping them read a difficult text which they then begin to understand and appreciate, or even love. Seeing my students go on to write books and to take things they learned in my classroom and pass them on to others is another great joy.

I want my students to learn how to read with sensitivity and to achieve depth of understanding for nuance, for the many mysteries and beauties of the English language. I want them to love poems the way I love poems, and if they want to write them, I want them to be able to do that confidently and skillfully.

I want to show people how literature – reading it, writing it, teaching and talking about it – how this can give a life meaning, how it can make the lives of others comprehensible, how it can become the center of something important and vital, how it makes us less lonely, perhaps even more empathic.

I have also been the student of some truly extraordinary teachers, and I try to transmit the best of what I learned from them to my own students, and in this way, I get to be a conduit to a tradition of learning that goes back generations.

SC: Speaking of students of poetry, do you have any advice for those who are considering submitting their work to this year’s contest?

MW: The thing I most hope for when I read a poem is to be surprised, and to have my attention rewarded by something I didn’t expect to find. I want to hear the uniqueness of individual experience, to get a sense of someone’s interior life, and to see the intersection of that inner life with language.

I read widely, and there’s not a single kind of poem or voice I’m looking for per se. I would urge those reading this who are considering entering to not assume I might like one kind of poem and not another kind. Also, entering a contest can be a good way of getting yourself to finish something, to take a risk and to seek an audience. So be brave, and let me see what you have!