The Architecture of Steve Wadzinski

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

It strikes you immediately.

It’s a long, narrow window, no more than a few inches wide on the long west side of the structure. If it were simply turned 90 degrees it could slip by almost unnoticed. Sure, it might register as a bit peculiar, but it’s not the window itself that steals your eyes; it’s the placement. It hovers just a few troubling inches off the concrete floor of the bronze garage, stretching six feet along the bottom of the corrugated metal exterior.

“Doesn’t it make you wonder?” asked Michelle Wadzinski when I questioned her on the purpose of the peculiar window stashed in its odd home by her architect husband, Steve Wadzinski.

“Well, yes,” I replied.

“That’s why it’s there,” she said.

Wonder. It’s what you do when you examine the buildings Steve Wadzinski constructed in Door County. You wonder why windows are where they are. What a room was meant for or where a ladder is leading you. And you wonder what this stunning, futuristic building is doing here at all.

But if you’re willing to take a step back and wipe clean your indoctrinated imagery of what a home should look and feel like, you reconsider what you’re viewing. And you begin to wonder whether you should toss everything you thought you knew about what fits the character of Door County out the window.

Defying Convention

Door County buildings may be some of the most critically judged in the country. Each business, each home, each woodshed in the back forty must fit into what is often called the “unique character and style” of the peninsula.

Whether there is such a thing is a matter of great debate, but nonetheless the phrase has been written into ordinance in some cases; in others it’s simply written into the minds of those of us who live here. Such limitations often serve to limit our designers and architects to the bland, the cheap, or even – despite our best intentions – to the environmentally destructive.

But some innovators have managed to maneuver around these preconceptions of what Door County living should be and build homes that challenge our image of what belongs here. Three of these homes stand tucked along lightly-traveled roads in Ellison Bay and Baileys Harbor, the work of the late Steve Wadzinski, an architect whose homes embodied the soul of a man who refused to allow his life and mind to be constrained by the boundaries of conventional wisdom.

Zomo

It looks cold as you approach, the green corrugated metal box in the foreground rising high before you looking like an industrial park building that got lost on its way back to the neighborhood. To the novice appraiser, the home Wadzinski dubbed Zomo hardly looks like fine design.

Tucked into the trees, just a couple dozen paces off the road, windows in shapes you haven’t seen since your high school geometry class hang uncomfortably in walls of green corrugated steel. They appear to be placed at random, some large, some tiny, and some like they have absolutely no business being there at all. It reminds you a bit of a young boy’s fort, made from the scraps of wood, cloth and metal Dad discarded or scoured from a dumpster in a treasure hunt.

But it’s all an illusion. What looks entirely accidental is in reality meticulously planned. It’s just that when Steve Wadzinski designed his homes he wasn’t as concerned with the view of those passing by as he was with those peering out.

Henry Grabowski, a friend of Wadzinski since the two attended architecture school together at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee in the early 1970s, explained his objective. “He liked to frame views of the outside from the inside,” Grabowski explained. “He was trying to bring the exterior into the interior.”

So a window wasn’t always placed to look right from the outside, but to shed light on a room from a specific angle or to direct your eyes down a wooded path. Or at the landing of a stairwell, situated to give the impression that one could walk out into the heart of the trees. Dave Damkoehler, another longtime friend of Wadzinski’s, spoke to the influence of those curious placements.

“His window placements had a kind of powerful tension about them,” Damkoehler said. “Windows were used with incredible care. They don’t line up with anything. They’re somewhere in between randomness and logic. He had this refined sense of placement and scale.”

Damkoehler is the Ben and Joyce Rosenburg Professor of Communication and the Arts at the University of Wisconsin-Green Bay. He hired Wadzinski to teach painting and drawing at the university almost two decades ago, when Wadzinski had collected Masters degrees in Architecture, Fine Arts, and Education from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.

Damkoehler would become a friend and mentor of Steve’s, with whom he shared a mutual appreciation of art and architecture in addition to a passion for motorcycles. “I sort of looked over his shoulder for a very long time,” Damkoehler explained. “I saw Steve as a kind of kindred spirit. He was a man attuned to a high degree of individuality.”

Wadzinski had a delicate presence about him, and an initial encounter would leave you knocked a little off balance. He didn’t greet you in the same manner or talk in the same rhythm as everyone else. In a conversation with him you got the sense he was starting from an entirely different perspective, a different base of knowledge than you were privy to.

“He challenged everyone else’s conventions,” Grabowski said. “He lived in a heightened state and urged people to actively participate in life and nature. A few minutes of conversation with Steve would take you off center and awaken you from your sleep, largely because he never took what was presented to him at face value.”

Some people use a lot of words to make a point, feeling a need to fill the empty spaces in conversation with noise, regardless of purpose. Wadzinski was the sort who could sit quietly for long stretches, absorbing the conversation, then one-up everyone with a single phrase or idea.

His designs come out of the same process. In the vein of the classic modernist school of architecture, he sought to minimize unnecessary ornament and angles. Yet he found ways to inject style and originality through the careful use of windows, doors, materials and light.

“Steve built like he lived,” Grabowski recalled of his friend. “He was frugal, spiritual. Not a window or door was put in for a frivolous reason. He used low-cost, maintenance-free materials. The corrugated metal he used is not much to speak of on its own, but he would mold them and cut windows into them to make it something more.”

The green and blue exterior walls of Zomo were chosen because they reflected the colors of the natural environment in which it sits. The stunning copper of the barn he called Rex II near Kangaroo Lake in Baileys Harbor was chosen because of the way the sun drapes over the landscape at different parts of the day.

“His whole lifestyle was about integrating nature and the outdoors with life,” Grabowski said. “He always said Door County was like his cathedral. The aesthetics of Door County, the sunsets, orchards, trees and water really inspired him.”

A home is at its most basic a shelter, and Wadzinski strove to create shelter while doing as little as possible to divide the living areas from the natural environment around him. He was attracted to Door County for its natural environment, and didn’t want to design his homes to eliminate it.

Both his Ellison Bay and Baileys Harbor homes feature large, open rooms with few interior walls. Spaces are bathed in natural light from an array of carefully-placed windows and skylights that soften any sense of confinement.

Once inside, the cold, industrial feel of Zomo’s exterior gives way to a warm, bright, wood-toned interior. The living quarters are on the second floor, a touch that gives even more power to those painstakingly placed windows which open to the upper reaches of the surrounding trees instead of to a driveway or landscaping.

His struggle to not separate home from nature extended to the most mundane aspects. The first-floor decks of his Ellison Bay home have no railings, giving them the feel of a pier extending into the water. Wadzinski’s builder and friend, Michael Thiem, explained his reluctance to add them. “Steve said it was such a nice place to sit and just let your legs dangle off the edge,” Thiem recalled. “He didn’t want to lose that.”

In Green Bay he once constructed a warehouse loft home in an industrial park. Surrounded by manufacturing centers, plants and automotive repair businesses, Wadzinski sought a way to weave the building into nature. He constructed a loft, reached via a ladder, that took you about eight feet off the floor where he placed his bed. To the side of the platform he placed three windows to frame the tops of a row of trees growing along the side of the building. Once again, the windows appear random, but they were there so that when you lay down to sleep and woke up, you would be looking not at an industrial park or a constricting wall, but into the trees.

At Zomo he took the concept a step further by installing an outdoor shower. “We never used the indoor shower, we always showered outside” Michelle said. “We encouraged guests to as well. There is nothing better than getting up in the morning, going outside and watching the sun come up while you’re taking a shower.”

His homes were built to leave small footprints on the environment as well. Noticeably absent from his work is the elaborate landscaping that accompanies so many other large homes. Wadzinski saw it as an unnecessary accessory, “like putting something where it doesn’t belong,” his wife said.

“He treaded lightly on property, no lawns or bushes,” Grabowski said. There are no long, paved driveways or parking areas. “Instead, he planted only pines and other indigenous plants.”

And he reached into the commercial realm to steal elements of efficiency and sustainability. “He borrowed from the commercial world and brought those ideas into the residential realm because he knew you wanted low-energy, low-maintenance buildings,” Grabowski said.

To this end he used thick, super-insulated walls to cut down on heating needs. The strategic placement of windows brings in natural light and vented windows and fans create natural ventilation. The interiors are indirectly lit, using the ceiling as a light fixture by shooting light off of it.

The metal façades of his creations require minimal maintenance, and the surrounding property needs no fertilizer, lawn-mowing, or weed control. The concrete floors keep the buildings cool in the summer. None of these aspects are based in high-cost, advanced technology ideas, but save thousands of dollars in energy bills and usage, as well as labor and upkeep.

His designs were often difficult to swallow, even for those working with him. Michael Thiem collaborated on many projects, including Zomo, Rex, and Rex II, with Wadzinski as his builder. Building permits were often a struggle, and even Thiem had his moments of contention. “Some of his design ideas clashed with normal conventions, and even grinded with me,” he said. “Some looked straight out of the Jetsons.”

Michelle estimates that Wadzinski left a library of over 500 plans and sketches behind. His most daring ideas were never built, including one in the shape of a sort of giant sofa, another like the crown of a ship, and other plans for his parents and friends shot down for their radical design.

But Wadzinski knew what he was after and was exacting in every detail of his projects. “We once picked through an entire pile of lumber to find a particular piece of wood,” Thiem recalled. “If it took that, he would do it. But he wouldn’t want to do it twice. And he expected that of all the people working for him. He expected their best work, and if he didn’t get it, he made them do it over.”

Gone too soon

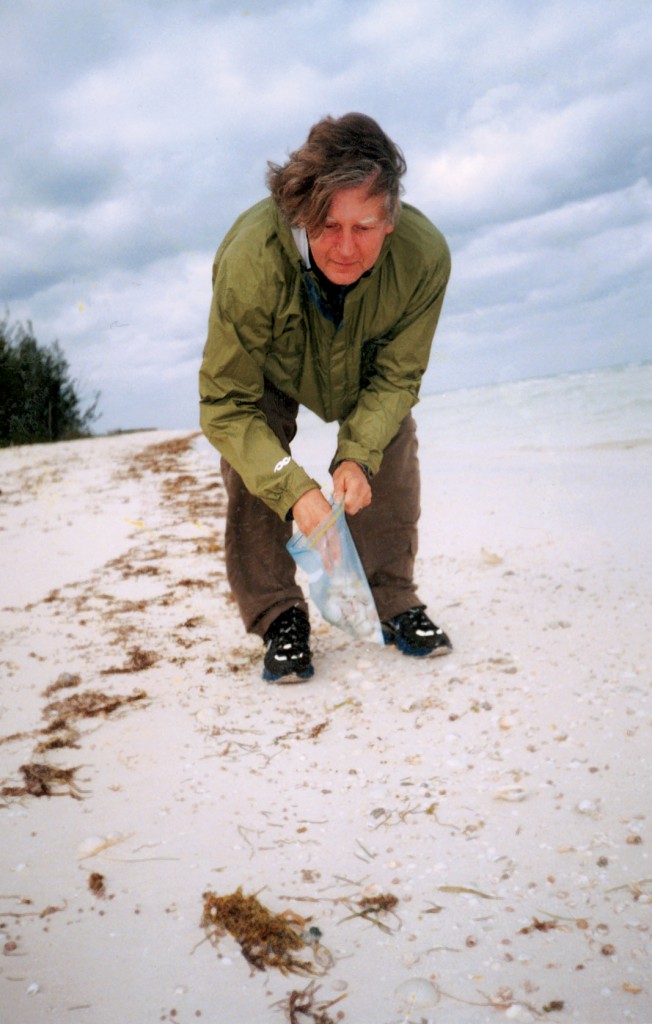

Wadzinski loved to ride his motorcycles, particularly his Ducatis. He skied competitively in his youth, and he told Damkoehler that riding a bike was the closest thing he’d found to skiing. “It was the feeling of your body moving through space, almost like a human insect or a bird.”

He reveled in the danger of it, but he was experienced, trained to race, and dedicated to safety. He always wore full leathers, a helmet, and took all the precautions.

“He would never even drive a car without a sunroof,” Michelle said. “I think he felt like the ceiling was coming down on him.”

On August 3, 2006 a signature, sun-swept Door County morning, Steve talked to Michelle on the phone and went for a ride. It was a route he knew well, one he took often on the way home from Leroy’s Water Street Coffee in Ephraim back to Rex I.

But there is a bend at the corner of Maple Grove and Gibraltar Roads that makes it difficult for drivers turning north on Maple Grove to see clearly. Some residents had been clamoring for a four-way stop for years, to no avail. The driver turning north didn’t see Wadzinski until it was too late, and no amount of skill or protection could save him from the impact.

After eight days in a coma, Wadzinski was taken off life support and passed away at the age of 53. He left behind a wife, two step children – Alex and Kelsey – whose lives he had helped construct for eleven years, the daughter he and Michelle shared – Eva, over whom he had doted in a manner his friends never imagined. “No one ever thought he could become a family man,” Michelle remembered, her eyes watering. “But he adored her. She was his diamond, an angel. He was an amazing father. I don’t think it ever occurred to him the love he could have for a child.” After Eva’s birth Steve’s signature became – StEva.

He also left behind two brothers and three sisters, and a long list of friends and acquaintances in diverse fields and endeavors who now share a common lament – they wish they’d known him better. But as Thiem explained, his diversity of interests made that impossible. “He just had so many things he wanted to do,” he said. “He couldn’t really take the time to reach out and get to know more people.”

Those who knew him well lost a profound influence. “I owe a debt of gratitude to him for raising my own consciousness to the things that are more dear in life,” Grabowski said. “He just got it.”

There are initial plans for a memorial to Wadzinski at Zomo. Nothing extravagant, just a pole extending into the sky where his urn will rest off to the side of the house, swaying slightly, sitting with the treetops, flying with the birds.

Until then, his homes stand as fitting memorials, places where one can get a sense of the man who built them, if only you allow yourself to wonder.