The Costs of CAFOs

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

S&S Agriculture Enterprises LLC is the only licensed CAFO in Door County. Photo by Len Villano.

Wisconsin farmers have learned to do more with less.

From 1960 to 2004, the state’s agricultural output grew by an average of 0.72 percent each year, while land inputs dropped by 0.68 percent and labor input dropped by almost 3 percent, according to the USDA.

And while agricultural efficiency is good for keeping cheap food on the shelves, it comes at a cost to the health of local environments and people.

“There’s a growing concern in Door County that we’re going to have an influx of CAFOs,” said Jerry Viste, executive director of the Door County Environmental Council (DCEC).

That’s why DCEC invited author David Kirby to speak about Animal Factory, his book about industrial farming on Aug. 22 at the Baileys Harbor Town Hall.

CAFOs, or Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations, are farms with over 1,000 animal units – which equates to 700 milking cows, 2,500 adult pigs or 200,000 meat chickens. They’re under special regulation by the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (DNR) because of the potential threats to water quality that arise when so much animal waste is generated in one spot.

Duescher’s Legendairy Farms is one of 15 permitted CAFOs located in Kewaunee County. Photo by Len Villano.

Animal waste creates environmental and human health concerns because it can contain germs like E. coli, which can make people sick. Antibiotics fed to livestock also end up in that waste, which leads to the spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria in the environment.

There’s only one registered CAFO in Door County, located on Old Elm Road in Sturgeon Bay. The owner of the operation was not available for comment.

But in Kewaunee County there are 15.

“It’s just a matter of time before they start moving up this way,” Viste said.

In one sense, they already are. The state requires CAFOs to spread their manure over a regulated amount of land so it’s less concentrated. Three CAFOs in Kewaunee County bring their manure to Door County to spread it on rented or owned land.

The environmental and health concerns Kirby addressed at his presentation are unique to large farm operations. Although smaller farms spread manure on their crops, it’s a different spread.

“This isn’t your grandfather’s manure,” said Lynn Utesch.

Lynn and his wife Nancy own a small farm in Kewaunee County near many CAFO operations. They work with Kewaunee Cares, a group advocating for responsible environmental stewardship in Kewaunee County.

On CAFOs, manure is collected into storage facilities along with the chemicals used to clean equipment, surface runoff from the surrounding area and copper sulfate, a heavy metal used to clean cows’ hooves. It’s stored as a liquid, so no oxygen can get into the mix.

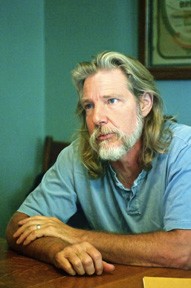

Lynn Utesch and his wife Nancy operate a small farm in Kewaunee County, where they are virtually surrounded by CAFOs. Photo by Len Villano.

The bacteria that break down manure exposed to the air are different than those in airless environments, like a lagoon. The bacteria in lagoons are smellier, Kirby said.

The Door County Soil and Water Conservation Department (SWCD) gets complaints about sound and odor emitted when large operations spread manure, said Dale Konkol, SWCD conservationist.

Permitted CAFO operators can’t spread manure on frozen or snow-covered ground, and they have to report their inspection records to the DNR.

“You do have more manure, so if there is something like a storage facility that were to fail it’s not like 100,000 gallons – it’s over 1 million gallons that could potentially spill,” said Thomas Bauman, DNR engineer. “There’s the potential for significant impact if those materials aren’t handled properly.”

If CAFOs don’t follow regulation after repeated warnings, the DNR can take them to the Department of Justice (DOJ).

Lynn said the DNR took a Kewaunee County CAFO operation to the DOJ after failures to comply with water quality regulations.

“We end up with issues,” Bauman said. “There are operations that have issues, there’s no doubt about that.”

At his presentation, Kirby pointed to costs of CAFOs beyond noise, stench and potential threats to water quality. He said the large concentration of waste leads to a buildup of methane – a potent greenhouse gas emitted from animal waste – and antibiotic resistant bacteria in the environment, or even in the food products.

“When you put too many animals in one place, diseases can spread, they can mutate,” Kirby said.

David Kirby, author of the best-selling book Animal Factory, presented at the Door County Environmental Council’s annual meeting about the far-reaching fallout of CAFOs. Photo by Alaneo Gloor.

While he understands the desire to produce and buy cheap meat from large farms and CAFOs, Kirby said it shouldn’t be the only option for consumers. Somehow, he said, we need to find a way to encourage small or medium animal producers to get in the market and stay there.

“We need to give [people] more options, we need to give them education,” Kirby said.

Giving smaller municipalities the option to prohibit CAFOs from operating in their communities is one way to deal with the issue, Kirby said. That way it’s up to the locals to decide what happens near their property.

Residents in Kewaunee County are starting to speak up against CAFO practices, Nancy and Lynn said. Families living near expanding operations are concerned with the dust blown onto their property, the stench of liquid manure, the runoff of waste and chemicals into their groundwater and the value of their property.

Others are concerned about roads worn down by trucks, mud and manure.

“There is a larger group of people becoming water monitors and becoming proactive,” Nancy said.