The Girl Who Knew Jens Jensen

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

Her parents christened her Malin, a popular name in Sweden, meaning true and trustworthy. When she started kindergarten, school officials changed it to Marlene. But it really didn’t matter, because from the time she was a wee girl, she has been called Tudy, the nickname her father gave her.

Her parents were Henny and Titus Ekman, immigrants from far northern Sweden. They were part of the “Evanston Swedes,” a close-knit group who loved to fish and loved Door County because it reminded them of home.

Tudy was introduced to art in kindergarten and attended school in Evanston through sixth grade. She was fortunate to spend those early years in a district with a visionary superintendent who was one of the driving forces behind the artistic enrichment of the schools in the early 20th century. It was a wonderful place for a child who realized early that art was her destiny.

The year 1943 brought big changes. Titus Ekman was a machinist, and friends who had moved to Door County told him about opportunities in the Sturgeon Bay shipyards, booming with wartime business. The family bought the building south of Baileys Harbor on Highway 57 that had been The Old Heidleberg.

“There was no electricity, no running water, no bathroom,” Tudy recalls. “There was a hand pump in the kitchen that worked sometimes. It was total culture shock.”

The two-room school in Baileys Harbor was an even greater culture shock.

“There was no art, no music, no creative writing,” she says. “I was a girl in love with horses, who had no horse. But I loved to draw them. I took a drawing to school one day and kept it under the lid of my desk until I dared to show it to Lee Tishler, who sat next to me. He was the only other person who seemed to me to be an ‘art type.’ The teacher, Ernald Viste, noticed and became enraged. He jumped up from his desk and rushed right at me. ‘We can’t have a mule like that around here,’ he shouted. He threw the picture back in my desk and slammed the lid down. That showed me how important art was anywhere in the town. It just didn’t exist.”

High school was no better – a far cry from the opportunities Gibraltar offers today.

“The building was grim,” Tudy says. “The only new facility was the gym and, of course, there were no sports for girls. And again no arts program of any kind. Some of the country kids were good writers, but that skill was considered of no value. I felt so bad for them.”

Tudy has long believed that she has guardian angels, and she’s sure they were looking out for her at that point in her life. During her freshman year at Gibraltar, Jens Jensen began offering winter classes at The Clearing. Somehow, Olivia Traven, one of the founders of The Ridges, knew of Tudy’s artistic talent and arranged for her to attend. One day a week for two years, she left school and rode to The Clearing with a group from Fish Creek.

Folks from Baileys Harbor brought her home.

“Going through the snow banks on that crazy road to The Clearing to get to and from art classes, I knew this was meant to be,” she says. “I was the little farm girl among all those adults. There were wonderful conversations coming and going. I can’t tell you how exciting it was. The whole group of people was amazing, and I was smart enough to listen.

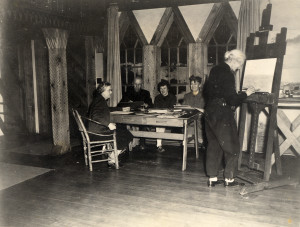

“It wasn’t like we sat down and had a class at The Clearing. It was more of a free-for-all. Very informal. You started a project and got some instruction, mostly from one another. Jens Jensen was a big storyteller, and he always had a rapt audience. He was a true philosopher, and he was interested in everything. I remember sitting there and listening to him talk about Mahatma Gandhi. Gerhard Miller was part of the group. He and Jensen together were unbelievable. Emma Toft was a fellow student. I’ve kept those memories my whole life.

“Jensen instantly judged people – whether he liked you or not, whether you ‘had it’ or didn’t have it. When I first appeared in his class, he asked if I had work ‘from when I was young.’ I told him I did, and he said, ‘Bring it in.’ I did, and apparently he was satisfied, because I was allowed to continue. Gerhard taught painting, and I must say of all the instructors I’ve had in my life, he was one of the best. Jensen taught woodcarving.

“After a while, I told him I’d like to try carving. He said, ‘Have Frank Oldenburg make you a stool.’ I came back with a little pine stool with a round top two inches thick. Frank gave me a few hints. Jensen said nothing and paid no attention to what I was attempting to do. Then one day he finally looked at my carving and said, ‘Yes, I can tell you have it in your hands.’ I knew he wasn’t going to mess with me unless he thought I had possibilities.

“I learned so much from my three tutors there. From Jens, the gift of philosophy and devotion to the land. From Gerhard, astute observation of nature, capturing its beauty, power and energy. And from Emma, a way of life, conserving and protecting nature. I spent a lot of time with her at Toft Point and got to know her pet crow, Rufus, and the orphan fawns she raised in her house.”

When Tudy graduated from Gibraltar in 1950, Jensen gave her a copy of his new book, The Clearing: “A Way of Life.” On the flyleaf, he inscribed, “Dear Friend, I hope you will ascend in your chosen field.”

Tudy worked her way through the School of the Art Institute of Chicago with a goal of working in advertising, and graduated with honors. Her first jobs were with the Chicago Tribune and the Schlitz Brewing Company. There was little time for art during the 15 to 20 years she was married and raising her children in Winnetka, but excellent adult classes in the school district got her involved again as a freelance illustrator, full-time graphic designer, art director and book designer.

In 1983, Tudy returned to Baileys Harbor.

“It was a new life,” she says. “I changed my name back to Malin and moved into the tiny two-story log cabin on Frogtown Road that my father had owned. There was no central heat, but I could once again do my drawing on my mother’s old table, where I’d started.”

She’s since filled the historic little house with antiques and her paintings, and the second floor, with lots of north windows, has become her studio.

From here Tudy has sent out a steady stream of work to more than 20 big-name national clients. She has exhibited at prestigious galleries all over the country. Her painting of Emma Toft was chosen by Northeast Wisconsin School Improvement Services (NEWIST/CESA 7) to advertise and introduce the documentary Emma Toft: One with Nature. The original hangs in the permanent collection of the Miller Art Museum, where Tudy is a board member. In 2000, she did a one-person show there that covered 150 feet of wall space. For nine years she taught workshops in beginning drawing for adults at Peninsula School of Art.

Her work has been reviewed in national magazines and major newspapers in the U.S and abroad, and she has been interviewed on TV and radio here and in Canada.

“I have a full, uncomplicated life,” she says. “This is such a splendid area to live in. I’m not exactly making a living, but I get by. I’m doing fine. I don’t need anything.”

Jens Jensen would surely agree that the girl he took under his wing 70 years ago has, indeed, “ascended in her chosen field.”