The Man Behind the Jacobsen Museum

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

ens Jacobsen was only 14 when Washington Island became his new home in the summer of 1881. Born on Als Island in Denmark, his parents decided to move the family to America so that their children would not be forced to serve in the Prussian Army. Jens was bilingual in Danish and German when he moved to the island and quickly began to learn English by splitting his time between school and working at Freyburg’s Mill packing shingles. When Jens became a United States citizen, he snow-shoed his way down to Sturgeon Bay to get his papers. Curiosity about the history of his adopted homeland sent him looking for fossils as well as arrowheads from the Potawatomi Indians who were the last tribe to inhabit the island before the settlers came. He started collecting in his earlier years and began amassing a sizable collection. Jens considered an Indian map stone which detailed the mainland, Washington Island and Little Lake to be his greatest find.

at Freyburg’s Mill packing shingles. When Jens became a United States citizen, he snow-shoed his way down to Sturgeon Bay to get his papers. Curiosity about the history of his adopted homeland sent him looking for fossils as well as arrowheads from the Potawatomi Indians who were the last tribe to inhabit the island before the settlers came. He started collecting in his earlier years and began amassing a sizable collection. Jens considered an Indian map stone which detailed the mainland, Washington Island and Little Lake to be his greatest find.

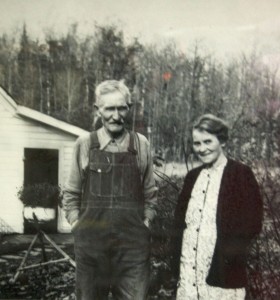

While relics of the past always held great interest for him, they were more of a hobby during his younger years. In 1895, Jens married Olive Garrett and together they had four children, three sons and a daughter. Their marriage was short lived as Olive died in 1909. It was important to Jens that the family not break apart any further after losing Olive and he raised the children on his own, never to marry again. The Jacobsens lived on a farm near the center of the island. During his career as a farmer, he was also a lighthouse keeper, a local politician, and an insurance agent.

A skillful carpenter as well, Jens began building on his property on Little Lake. He constructed 14 cabins all in the Danish style of keeping the logs vertical versus horizontal. He also built all of the furniture for the cabins. In 1931, he opened the Jacobsen Museum to showcase his lifelong collection of native artifacts. The concept of opening a museum was laughable to some. Jens politely ignored those saying that no one would ever come and pressed on. His instinct was correct; people did want to come. Drawn in by the quiet beauty of Little Lake, the scenic grouping of the cabins, and Jens’ natural story telling  abilities, sightseers began enjoying what is now the oldest museum in the county. Jens was honored by the Wisconsin Historical Society and the National Geographic Society for his historical discoveries. Before long, Jens was as well known with visitors as he was with islanders. He is also credited with beginning the cottage rental industry on the island.

abilities, sightseers began enjoying what is now the oldest museum in the county. Jens was honored by the Wisconsin Historical Society and the National Geographic Society for his historical discoveries. Before long, Jens was as well known with visitors as he was with islanders. He is also credited with beginning the cottage rental industry on the island.

Two of Jens’ grandsons, brothers Harold Sunstrom (Sister Bay) and Russell Sunstrom (Fish Creek), remember going to the cottages in the summer as little boys in the late ‘30s. They took some time on a Sunday afternoon to remember their grandfather. Little details were recalled fondly, such as Jens always carrying peppermint candies and lemon drops in his pockets for his grandkids and his never seeming to need a flashlight when walking in the woods at night. “He often referred to himself as the most photographed man of Washington Island,” Russell relates as he and Harold share a laugh. Harold remembers the working side of their grandfather, saying, “Well, I suppose he held every possible job on the island because he had to. Farming was tough.” Hardworking by all accounts, Jens also had a great imagination and a creative side. He wrote poetry, was a skilled artist, and created a lot of scrollwork carvings which are featured in the museum today. Harold seems to have inherited more than a few traits from his grandfather as he, too, farms and creates beautiful Danish scrollwork carvings.

“Uncle Bill would meet us at the ferry with his Model A Ford and take us to Little Lake as Grandpa did  not drive,” Russell reminisced. “The museum was up on a hill from the lake with his summer home in the middle. By the lake, he had a dock with rowboats and around the boats water lilies were in bloom.” Their other uncle, Ralph, ran the museum after Jens passed away in 1952 at the age of 85. By 1964, Ralph was unable to run the museum any longer which is when it was donated to Washington Island by the Jacobsen family. Since then, it has been carefully maintained by curators such as Carmen Klingenberg Lucke (1968 – 1988), Jeannie Hutchins (1997 – 2007) and Sandy Green (2007 – present).

not drive,” Russell reminisced. “The museum was up on a hill from the lake with his summer home in the middle. By the lake, he had a dock with rowboats and around the boats water lilies were in bloom.” Their other uncle, Ralph, ran the museum after Jens passed away in 1952 at the age of 85. By 1964, Ralph was unable to run the museum any longer which is when it was donated to Washington Island by the Jacobsen family. Since then, it has been carefully maintained by curators such as Carmen Klingenberg Lucke (1968 – 1988), Jeannie Hutchins (1997 – 2007) and Sandy Green (2007 – present).

Upon entering the museum, visitors can see Jens’ cherished Native American artifacts and tribal maps, and then segue into the mid–19th and early 20th centuries. In the size of a two-room cabin, the Jacobsen museum houses the stories of so many. From little snippets like Carl Koyen’s property tax bill of 1897 in which he paid $8.90 for 80 acres, to personal tales like that of island resident and polio victim Violet Llewellyn, whose special hand-held controls enabled her to drive a taxi for 39 years. Her specially-designed exercise bike, invented by an ingenious islander, is on display. There is a traditional Chinese wedding dress that was brought to the museum in 1964 by Far East missionary Carrie Anderson as well as World War II photos, shipwreck lists, Jens’ scroll saw, and a Homesteaders Land Grant signed by Ulysses S. Grant on June 30, 1875. The variety of the collectibles is as broad as Jens’ interests and talents. Also notable are the larger pieces outside of the museum such as an old time rock crusher, a rudder from the steamer Louisiana which was grounded in Washington Harbor in November, 1913, and an anchor that was recovered near Plum Island.

There will be some who breeze through the museum stopping briefly to note what an old-fashioned dentist chair looks like and then continue on, but the more observant will take the time to note what a historical treasure the Jacobsen museum is. They will imagine the fear and excitement of arriving in a foreign country where the language was so different; they will wonder what it must have felt like to have electricity for the first time in 1945; they will picture themselves getting the news that a loved one’s boat was lost in the unforgiving waters of Death’s Door; they will compare the size of their houses now to that of the tiny cottage; and they will ponder how long the museum will exist after they leave, hoping the answer is decades. All at once, the Jacobsen Museum is a personal account of an immigrant’s life and the collective biography of the people who have passed through the island.