“The Paris Wife”

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

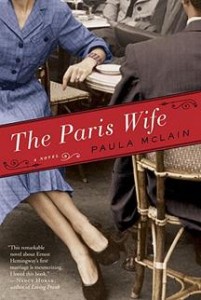

The Paris Wife

By Paula McClain

Ballantine Books, 2011

Released February 22

Ernest Hemingway was a man’s man, glorying in those things male: fishing, hunting, fighting bulls, going to war, and enjoying fleeting love. Feminists often dismiss him as a male chauvinist and close the book. But many of us with comparatively drab lives fantasize about grace under pressure, running with the bulls, and life on the Left Bank in Paris. Paula McLain’s novel The Paris Wife should please both groups.

The Paris wife is Hadley Richardson, the first of four women Hemingway would marry. And while the famous author called many places home, this story deals primarily with his life as an ex-pat in France and the people that he met; Ezra Pound, Gertrude Stein, Alice B. Toklas, F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald are the most famous among his friends.

While “people who actually lived appear in this book as fictional characters,” McLain noted, “it was important for me to render the particulars of their lives as accurately as possible, and to follow the very well documented historical record.”

Readers of Hemingway will enjoy the opportunity to revisit some of the scenes that appear in his work, in particular those familiar from A Moveable Feast and The Sun Also Rises. Ah, the elation of freedom and adventure, but oh, the depression from a life of dissipation. Fictional characters, like their real-life counterparts, drink too much, smoke incessantly, and prove habitually unfaithful in love.

As a writer of historical fiction McLain has done her homework, an achievement that contributes to the success of the history but lessens the impact of the narration. Ernest Hemingway, the iconic American author, is humanized as we follow the struggles of a young writer attempting to make a name. We share the trials of young love and marriage and fatherhood. And we shudder as we observe the consequences of a series of bad choices that the published author makes while ascending to fame.

Hadley Hemingway, the Paris wife, narrates the story, and while ostensibly hers is the tale told, in reality she becomes the prism through which the reader examines Ernest Hemingway: her observations bring the subject into a sharper focus.

“At home, we were both sick,” the narrator recalled, “one after another, in the chamber pot. The dance hall was still roaring with drunks when we went to bed; the accordion had risen to a fever pitch. We nuzzled forehead to forehead, damp and nauseous, keeping our eyes open so the world wouldn’t spin too wildly. And just as we were falling asleep, I said, ‘We’ll remember this. Someday we’ll say this accordion was the sound of our first year in Paris.’”

But while the book satisfies the reader’s curiosity regarding thoughts, feelings, and motives of Hemingway (both factual and imagined), the story ultimately is diminished by the authenticity of the narration. Anyone with a basic understanding of the Hemingway biography will not be turning to the end to learn the conclusion. And like an audience attending a Shakespearean tragedy, the reader feels a pervasive sense of grim inevitability as the pages turn.

The result is a work of fiction that is certainly interesting (at times, highly so), but seldom compelling. This is not a page-turner, but rather a work that satisfies curiosity, like snooping through boxes of old letters or paging through vintage photograph albums, letting imagination (this time the author’s) fill in the gaps.

And the portrait of Hemingway that emerges is one of a man who may have admired those exhibiting grace under pressure, but at the same time, seldom doing so in his own flawed life. Hemingway the hunter, the warrior, the lover, was ultimately far more like The Sun Also Rises character Jake Barnes than Pedro Romero, the bullfighter who faced charging beasts without flinching, without artifice, and with the grace of a dancer. Barnes, on the other hand, was an imperfect protagonist, damaged both psychically and physically by war, unable to find success in work or in love, instead seeking solace in drink and wilderness and thoughts of what might have been.

But while Hemingway’s life ended in a self-inflicted tragedy, The Paris Wife achieves the resolution of modern times. Hadley does not fade away, the wronged wife destroyed by betrayal, but moves on, as did Hemingway. For this is modern life, the essence of Hemingway’s work and of McLain’s fictionalized biography.