The Rise and Fall of the Ahnapee & Western Railway

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

For most people today, the initials A&W bring to mind a frosty mug of root beer, but for nearly a century folks in northeast Wisconsin knew it as shorthand for the Ahnapee & Western Railway.

Mark Mathu grew up in New Franken, Wisconsin, about 35 miles south of Sturgeon Bay in Brown County, where the tracks of the A&W line were a fixture. Local kids walked the tracks to school each day, and they’d place pennies on the tracks, hoping the train would flatten them into massive, thin pancakes when it went by.

“We did it all the time,” he remembers fondly, “but we never did find a penny after it went by.”

Long before Mathu and his childhood friends knew it as part of small-town Wisconsin life, Casco founding father Edward Decker saw building a railroad as a risk worth taking. According to Stan Mailer’s book Green Bay & Western, Decker – who owned 10,000 acres in and around Casco as well as The Enterprise, a Kewaunee newspaper – sought to build it to enhance his business interests.

He advanced most of the funds to get it started, and more was raised through several different bonding issues ultimately totaling $671,000 (over $16 million in today’s dollars).

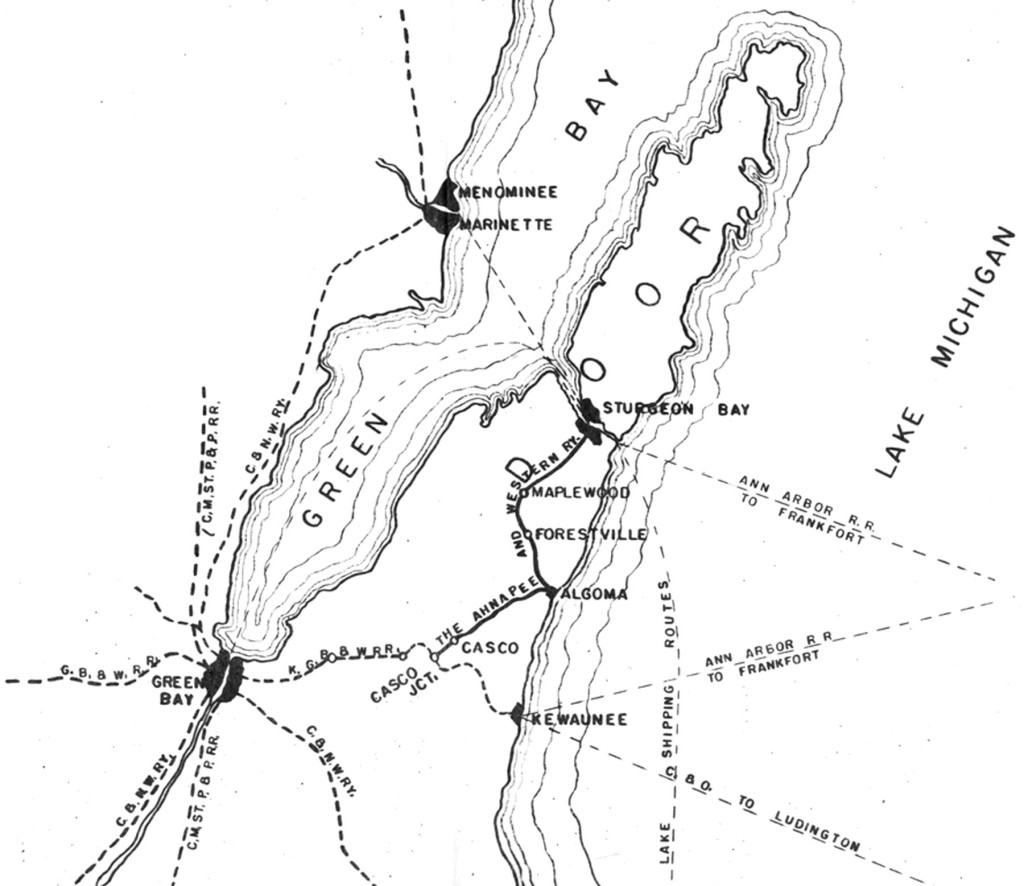

The A&W was incorporated on August 18, 1890 as a short line, connecting to the Kewaunee, Green Bay & Western Railroad (GB&W) at Casco Junction. By 1892, track had been laid to Ahnapee (renamed Algoma in 1897), and two years later it reached Sturgeon Bay. The line’s 34.5-mile run also included stops in Rio Creek, Forestville, Maplewood and Sawyer.

Mathu is now a civil engineer living in Whitefish Bay, Wisconsin, where he works for HNTB engineers, devoting most of his time to designing bridges around the country. About 10 years ago his mind wandered toward the idea of building a model train in his basement, and he began researching, soon realizing that the A&W of his youth was one of the most unique in the country.

He started a website, www.greenbayroute.com, devoted to the GB&W and began getting emails and phone calls from others with information and stories to share about the line. Now he serves as secretary of the Green Bay & Western Historical Society. While his initial interest in the railroad was sparked by nostalgia, it’s clear when he talks that he is equally fascinated by the entrepreneurial spirit and engineering feats of its founding.

“It really is amazing that they built it,” he says. “With shipping going on both sides of the peninsula it really was a gutsy move at the time.”

Door County was the last county in Wisconsin to get rail service, as there was little interest in running a line to a dead end. The builders had to run the line through the swamps south of Sturgeon Bay, move materials to remote areas, and engineer their way around creeks and over Sturgeon Bay.

“To get all the ties, to move earth to make a railroad up there, it was an impressive feat back then,” Mathu says. “And consider what it must have taken just to raise the capital in 1890, with the Panic of 1893 right around the corner. That was the worst economic collapse until the Great Depression.”

To reach Sturgeon Bay’s east side, where the shipyards and eventually a bus depot were located, the railroad had to cross the ship canal. In 1887, John Leathem, Tom Smith and Rufus Kellogg built a bridge, consisting of a wooden plank road on a timber pile trestle across the bay. It featured a center pivoting truss bridge to allow for boat passage through the canal, and they received a 25-year charter to operate it.

In 1891, the A&W received grants totaling $76,000 from the city and county to construct a line to Sturgeon Bay, and the rail crossing was completed in 1894 by attaching tracks to the toll bridge. For decades, the bridge carried both automobiles and trains.

At the end of the charter in 1911, the bridge reverted to municipal ownership; the City of Sturgeon Bay then operated it using tolls – 75 cents for threshing outfits, 25 cents for team and rider and 5 cents per head for foot passengers. After the new highway bridge on Michigan Street in Sturgeon Bay opened in 1931, the city sold the old swing bridge back to the A&W for $1.

By the turn of the century Decker was in dire financial straits, as an investment in the Jackson National Bank of Chicago had failed terribly, taking with it the Decker empire. In 1906, the line was sold to the GB&W, but Decker never recovered, dying nearly destitute in 1914.

The railroad he founded, however, was doing much better than him. The early years of the 20th century were a busy time for the A&W. In 1906, the Forestville Station shipped 199 carloads of hay, 42 of grain, 39 of peas, 27 of sugar beets, 25 of stock, two of posts, two of wood, one of junk, one of household goods and 389,171 pounds of LCL (less than carload lots) of cargo.

Andy Laurent, vice president of the Green Bay & Western Historical Society, grew up visiting grandparents in Casco and Rosiere and is a serious student of A&W history now working on a book about the line. Laurent, who resides in South Bend, Indiana, writes on www.greenbayroute.com that on a given day in the 1930s, the 17 freight cars on the A&W train, originating from 10 different railways, carried a variety of loads including: liquid propane for Wulf Propane in Sturgeon Bay; a load of sawdust for Plumber Woodworking in Algoma (manufacturers of Badger Brand toilet seats); 50-pound blocks of salt for the Door County Cooperative; and an empty insulated boxcar for Badger Foods (formerly Reynolds Brothers Canning) in Sawyer.

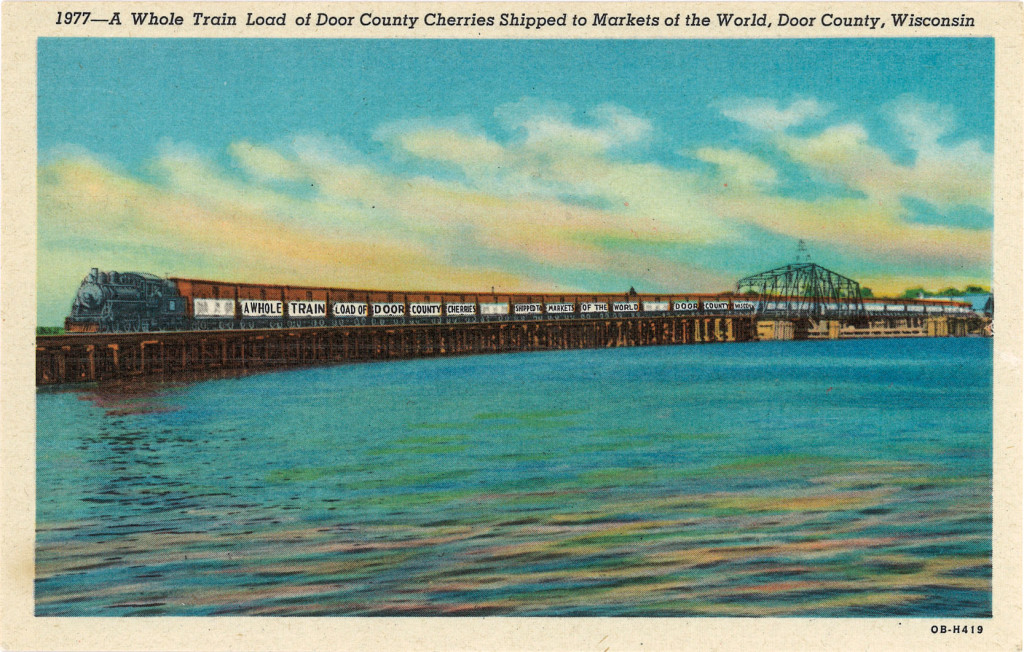

The railroad gave options to Northeast Wisconsin businesses that previously had to depend on shipping by water. For example, the Van Camp Condensery in Sawyer developed into a major economic influence in the community. By the late 1920s, it was not unusual to see a train leave the Sawyer side of the bay at least once a week pulling 20 cars full of cartons of condensed milk.

The railway has since been converted into the Ahnapee State Trail, a multi-use path between Door County and Kewaunee County. photo courtesy of Friends of Ahnapee Trail.

John Thenell of Sturgeon Bay, whose father managed Martin Orchards – then the largest in the world – from 1938 to 1952, remembers when that orchard alone was producing 250,000 pounds of cherries a day, and the A&W left Sturgeon Bay with whole trains full of cherries.

The A&W also provided passenger service to the tourists who flocked to the peninsula. In 1914, the Door County Special from Green Bay to Sturgeon Bay was added, attracting passengers who connected to the GB&W from Chicago and Milwaukee and providing competition for the steamship lines that brought vacationers to Door County shores.

Tourists could travel north from Sturgeon Bay via Yellow Car & Transit Company’s “Buick Special” service, which ran to Ephraim twice a day. For $3 extra they could get to the U.S. mail boat landing in Ellison Bay.

In an interview for the book A History of Kangaroo Lake, the late Jim Finley recalled the first trip he and his dad made to Door County in 1915, taking the Northwestern train from Chicago through Green Bay and transferring to the A&W at Casco Junction for the rest of the trip. Art Wilson and Frank Kellogg met them in Sturgeon Bay in a 1914 Ford touring car to take them the rest of the way.

By 1917, Charlie Panter, owner of the popular Panter’s Hotel in Baileys Harbor, acquired vehicles to meet the trains in Sturgeon Bay, and into the 1960s bus lines would provide service to Northern Door.

Regular passenger service came to an end in 1937. The Depression played a role, as did improved roads that made bus and auto traffic more attractive options. In the waning days of World War II, however, passenger service returned briefly to bring German POWs to work in the Door County fruit harvest.

A Slow Decline

Without passenger service the A&W survived because it had predominantly focused on transporting goods, but by the 1940s it was struggling. As it began to lose money the parent railroad, the GB&W, wanted to sell or abandon it. Local businessmen led by Vernon Bushman of Bushman Dock & Terminal Company fought to keep it alive, and in 1947 it again became an independent line.

Business continued to drop off during the next decade, and in the 1960s service was reduced to three days a week. The railroad was threatening to abandon service to the east side of the city because of the deteriorating condition of the bridge. The city and the railroad tried to get funding for a replacement railroad/highway bridge but were unsuccessful, and it was sold back to the city for $1 in 1966.

Then Sturgeon Bay’s major shipper, Evangeline Milk, went out of business. In May 1968 the Sturgeon Bay bridge was condemned, and the A&W abandoned its line north of Algoma later that month. The last train to run in Door County left from Sturgeon Bay on September 4, 1969, its cargo an old diesel engine. Door County had been the last county in Wisconsin to receive railroad service, and now it was the first to lose it.

Mathu remembers that during this era, the heart of his childhood in the ‘60s and ‘70s, the railroad didn’t seem stable. “At the time it seemed they were talking about it closing forever,” he says, though he never thought it would. For years Algoma Hardwoods (later the Champion Mill) was the only regular customer.

“It seemed that the fortunes of Algoma Hardwoods went hand-in-hand with the railroad,” Mathu says. “It started in the 1890s as Ahnapee Seating & Veneer Company, about the same time as the railroad. The company [its name changed several times over the years] was sold to Champion in the late 1960s, and they kept the line going from Casco to Algoma for a few years.”

Service now dropped down to two cars a day. On New Year’s Eve, 1970, the line was sold to McCloud River Railroad, a division of U.S. Plywood-Champion Papers, which now owned the Champion Mill.

In 1977, Itel bought the McCloud River Railroad and a year later acquired the GB&W, making the 13.75-mile A&W line a GB&W branch once again.

When the Kewaunee River Bridge was washed out in 1986, it was deemed unworthy of repair, and just a few years shy of its 100th birthday, the life of the A&W railroad came to an end, making its final run on March 25, 1986.

For Mathu, Laurent, and many others who grew up with the train as part of their day-to-day lives, looking back at the era of the railroad summons nostalgia and a touch of sadness.

“I took it for granted that it would always be there,” Mathu says. “I thought it was eternal, but I guess it just wasn’t meant to be.”

Information for this article was garnered from the exhaustive website devoted to Northeast Wisconsin rail history, www.greenbayroute.com, as well as Stan Mailer’s astoundingly detailed book, Green Bay & Western, available from Hundman Publishers.