The Risky Careers of Christmas Schooner Captains

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

When the late summer storms on the Great Lakes began to stir, and the gales of November rattled the very souls of the schooners, the lake captains saw their transport business diminish. But there came a realization of a new seasonal run — Christmas trees! Christmas trees for those cities and communities where pine forests were too far away to conveniently acquire a tannenbaum. In the local vernacular the captains of the schooners were “hustling Christmas trees.”

The list is long, and many of the voyages lucrative, for the Christmas tree ships that sailed Lake Michigan. It was a long and harrowing era of schooners and scows; most that were involved with the tree-trade were built between 1848 and 1913, with the majority being of 1860-1870 vintages. They were launched from the shipyard cities like Cleveland and Conneaut, Detroit and South Haven, Manitowoc and Sheboygan.

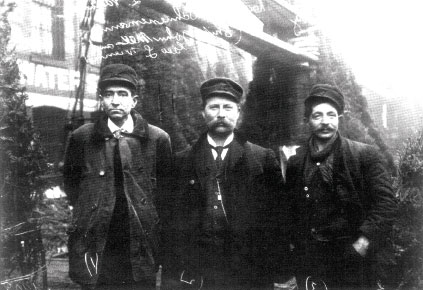

Fathers and sons and brothers, and even once a wife, captained the schooners and scows. Names like Arthur E. Dow, Herman and August Schuenemann, John P. Clark, William Armstrong, William H. McDonald, Hans Hansen, David Dall, Ole Olson, just to name a few, appear again and again as captains of ships hauling Christmas trees as their end-of-year cargoes. These men earned reputations for their seamanship or sometimes lack of it; they were known for their exuberance and bravery. Captain William Armstrong of Ahnapee was as well known for his bar fighting as he was for his sailing abilities. These were tough guys, as evidenced by Captain August Brann’s experience: a December 6, 1901 Sturgeon Bay Advocate report said that from the deck of the Nancy Dell, which lay beached off Indiana’s Dune Park, after sailing from Baileys Harbor, “Capt. Brann stood watch until his beard was frozen to his clothing and only when he was certain his schooner was anchored safely did he retire from his post.”

The ships carried all kinds of cargoes from Christmas trees to farm produce to timber to manufactured goods. The captains and companies would take consignments of Christmas trees to Chicago or Milwaukee — to hundreds of towns, sometimes even as far as St. Louis.

As early as 1872 the Milwaukee Sentinel noted that trees were a “drug on the market at 25 cents.” During a two-day period in December of 1888 seven train-car loads and one schooner full of Christmas trees (12,000 to 15,000 total count) arrived at Milwaukee’s West Water Street and were sold before even being unloaded. So many schooners were coming into Chicago and Milwaukee with Christmas trees that the late arrivals found well-saturated markets.

The Christmas trees were cut from the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, the Door Peninsula, and other parts of Wisconsin. Farmers, out-of-work woodsmen and hard-up sailors became seasonal lumberjacks. The trees turned into a cash crop for the financially strapped farmers. The “down-lake” markets were fueled by the influx of German settlers and the increasing popularity of traditional tannenbaum-centered Christmas, said the Milwaukee Sentinel in 1888.

The schooners were the lake-going equivalents to the trucking lines of today. The boats averaged 125 gross tons and 95 feet, but varied considerably. The larger schooners and at least one steamer carried up to 12,000 Christmas trees, but most carried 500 to 3,000 trees. Of the more than fifty schooners and scows that sailed with cargoes of Christmas trees into the early 1900s, 26 were wrecked or lost on Lake Michigan. The average life span of a schooner on the lake was about 35 years.

Some of the gales were legend, as were the survival and refloating of some of the ships. The gale of November 1881 beached the schooner-scow Lady Ellen, Captain McDonald’s ship. Then there is the fate of the Sheboygan-built schooner La Rabida. Captained by Arthur E. Dow of Manitowoc, the aged La Rabida was wrecked in a late November 1906 gale and her crew nearly died of exposure. That same storm damaged 17 vessels and caused 43 fatalities on Lake Michigan. Dow was a tough old seaman, and later reported, “she was leaking badly” as they struck bottom 200 feet from shore at Point Patterson. The schooner was pounded to pieces by the storm. The crew of four was literally thrown upon the beach by the waves. Dow mustered his crew to salvage thousands of Christmas trees that washed ashore. They somehow held death at bay all night while exposed to the freezing wind. The crew managed to transfer the trees to railroad cars at Naubinway in Michigan, from whence the precious cargo made it to market in time for the holidays.

The Schuenemann family is perhaps the most well known family that participated in the Christmas tree trade. Their story is romanticized through the characters of “The Christmas Schooner” musical. That show has been brought to Door County through the efforts of Gloria Hanson, and under the direction of Jeanne Hopson is part of the Door Community Auditorium performance schedule.

Herman and August Schuenemann were brothers who shipped Christmas trees for many years. August, the older brother, was lost when his schooner S. Thal carrying Christmas trees to Chicago in 1898 fell prey to a November gale. As with his brother, Herman’s life at sea was risky and would ultimately catch up with him. Herman chartered and owned many schooners, each succumbing to the whims of Lake Michigan. The M. Capron was wrecked off Baileys Harbor in 1875, and the Mystic ran aground on Pilot Island off the tip of Door County, and in 1883 was struck by a steamer in a dense fog. Herman acquired the family’s largest vessel, the schooner Mary L. Collins after she was wrecked and salvaged in 1893 on South Manitou. The Collins had already run aground ten years earlier at Sister Bay, so she had a history of bad luck. In 1899 Herman sailed her from Michigan’s Upper Peninsula loaded with 12,000 Christmas trees that he had purchased from the Chippewas. But in the fall of 1900 the ill-fated ship was wrecked at Little Harbor, just south of Manistique.

Herman Schuenemann was known in Chicago as “Captain Santa” because he’d sell Christmas trees right off the schooner’s deck at the Clark Street Bridge for less than fifty cents each. Herman wanted to promote the traditional German Christmas values, and was said to give trees to those who could not afford them. He once told a Chicago paper he shipped the trees every year “because of the joy I find in the eyes of the children that come aboard my ship to find the perfect tree for Christmas.” On his final and fateful voyage on November 23, 1912 he sailed the 44-year old three-masted Rouse Simmons out of Manistique. The captain was in his third year of leasing the vessel from M.J. Bonner of St. James, Michigan. The captain knew that one of the biggest problems with winter runs was ice build-up on the deck and riggings of the schooners. On that late November day forty-foot waves pitched up at the tired and water logged 123-foot long schooner, and ice built up on the deck, riggings and cargo of Christmas trees. All 17 hands were lost when “the storm chased them down.”

By all accounts the Rouse Simmons was a tired old ship. The Chicago Daily News ran a December 5, 1912 article about Captain Nelson’s daughter, who said her father appraised the vessel as “unseaworthy.” “My father didn’t want to take this cruise,” said Mrs. Verner in the article. “Capt. Schuenemann came to father,” she said, “and begged him to take charge of the boat. We — my husband and myself — had begged him to give up the lakes and he had consented. Then, to please Schuenemann, he said he would take one more cruise. Before he left he shook his head regarding the Rouse Simmons. He said that it needed a general overhauling and had asked that it be done. However, he said it was not done and things were left as they were.”

Sailor Hogan Hoganson left the Rouse Simmons because he said, “It was the rats that gave me my first ‘hunch’ that trouble was ahead for the Rouse Simmons — the rats always desert a sinking ship.”

Another crewmember, Steve Nelson, complained to the newspaper about the overloaded, poorly maintained schooner. He said, “Then I quit. Captain Schuenemann, the owner of the cargo, told me I would get no money unless I stuck for the cruise, but I had some money and so I took a train for Chicago. Here I am — and the others?”

So it seems Herman Schuenemann’s big heart, his entrepreneurial drive to deliver more trees, or his poor judgment brought on the end of him and his crew. For decades following the wreck Christmas trees would wash up on the shores of Two Rivers. Then in 1971 the ship was located off the coast of Two Rivers, sitting upright on the bottom of the lake with Christmas trees still roped to the deck. Herman Schuenemann’s wife, Barbara, continued the tradition and sold trees from the deck of the Oneida and Fearless schooners over the next 21 years.

The tradition was recently rekindled in 1999 when historical enthusiasts enlisted the Coast Guard cutter Mackinaw to bring trees from Cheboygan, Michigan to Chicago. As tradition would have it, some are even sold from the deck of the ship.

The life of the Christmas tree captains and their schooners was wild because of the November gales and risky because of the competition. It was rarely romantic, but always hard work. So, during this holiday season, toast these sailors of days gone by as you decorate your Christmas tree.