Think You Know a Lot about Jean Nicolet?

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

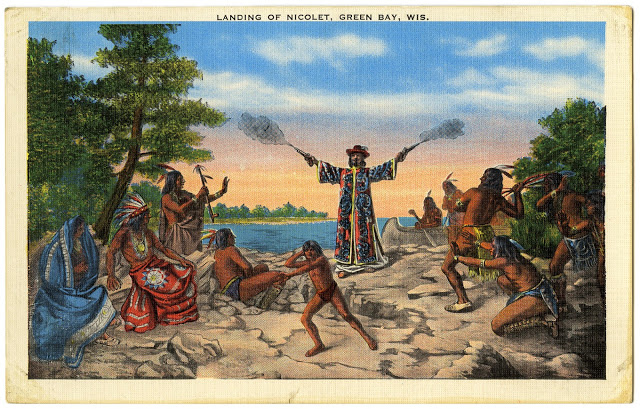

If you grew up in Wisconsin during the 20th century, you probably learned in fourth- or fifth-grade social studies that Jean Nicolet was a great explorer who came to the Great Lakes expecting to find a route to the Pacific. He landed at (take your pick) Menasha, Kaukauna, Kewaunee, Red Banks or Chicago wearing a Chinese robe to greet people he assumed to be Chinese.

Wrong, all wrong. Patrick Jung, a Milwaukee School of Engineering professor and the author of the 2018 book The Misunderstood Mission of Jean Nicolet: Uncovering the Story of the 1634 Journey, has spent decades studying Nicolet and early Wisconsin Indians. He shared his research at a recent dinner meeting of the Door County Historical Society.

“Those are cockamamie stories about Nicolet,” Jung said. “He wasn’t famous during his lifetime. For the most part, information about the man and his trip to Lake Michigan died with him. The actual evidence is very thin – four pages written by Jesuit priests that were translated and published more than 100 years ago. But people want heroes. Myths grew up. The stories were told and believed for generations and – especially in the 20th century – were accepted as fact.”

An earlier book by Jung and Nancy Oestreich Lurie, formerly the curator of the Milwaukee Public Museum, pointed out that misinformation about Nicolet was not only widely printed – in textbooks, Encyclopaedia Brittanica and many other places – but also depicted in half a dozen murals in public buildings in Wisconsin, on at least two historical markers, on a 1934 U.S. postage stamp and in a larger-than-life bronze statue in Wequiock Falls Park near Red Banks (paid for, ironically, with money collected by Wisconsin schoolchildren in 1939-40).

Samuel de Champlain, the commandant of New France in North America, founded the town of Québec in 1608 and took Nicolet there in 1619 when Nicolet was about 20 to serve as a diplomat and interpreter. Nicolet spent a number of years living with the Nipissings and became fluent in the Algonquin and Iroquois languages.

Taking Indians from all over New France down the St. Lawrence Seaway to Québec on annual trading expeditions, Nicolet heard about war being waged by the Puans (the French name for the tribes later known as the Winnebago and Ho Chunk). Nicolet was sent as Champlain’s emissary to facilitate a peace treaty to preserve safe trade.

Both Champlain and Nicolet were educated enough to know that the Great Lakes did not lead to the long-fabled Northwest Passage to the Pacific and on to the Orient. Nicolet was chosen for the mission to the western Great Lakes because he could read and write; he knew the native culture; and he could communicate with the Indians in their native language.

Nicolet was Catholic but not an explorer, and he was not wearing a Chinese robe. The pictures painted in the 20th century got it wrong, probably because of a bad French-to-English translation of the scanty reports written by the Jesuit priests. Their mention of a cape of Chinese damask – something worn by every 17th-century French man of Nicolet’s social standing – was incorrectly interpreted as a robe from China. Thus, the assumption was that his destination was China, where he expected to be appropriately dressed to greet Chinese people.

Franz Edward Rohrbeck’s 1910 mural in the Brown County Courthouse shows Nicolet wearing a long, red robe, as does a similar mural by Edward Willard Deming in the state Capitol, and it is that scene that was depicted on the 1934 three-cent stamp.

So where did Nicolet – sans Chinese robe – really land in 1634? Champlain was, for his time, a good mapmaker. In fact, his 1632 map of Lake Michigan was the first to outline the Door Peninsula. Nicolet’s expedition knew where it was going. The Indians who accompanied him were from a tribe that had been following that trading route for two centuries.

“It’s highly probable, 75 to 90 percent,” Jung said, “that they landed somewhere between Little Bay de Noc and the mouth of the Fox River, and likely 40 percent probable that their final destination was somewhere near the present city of Marinette.” (By the way, it’s extremely likely – close to 100 percent – that Nicolet was the first white man in Wisconsin. At least that much of what we were taught is true. Probably.)

Why did they land on the western, rather than the eastern, shore of Green Bay? This area was part of a vast Indian empire that stretched at least from Lake Michigan to the middle Fox River, possibly as far west as the Mississippi River, and as far south as Chicago. Wars were ongoing among the tribes, and Nicolet’s guides knew that the Menominees on the western side of the bay were likely to be more friendly to a European than the Puans on the eastern shore. “A visit to the Puan villages,” Jung said, “might have been suicidal.”

After his trip of six to 10 weeks, Nicolet returned to live the rest of his life with the Algonquins, serving as an interpreter for priests and traders. Although he spent much of his life on the water, he never learned to swim. He died on Oct. 27, 1642, when a sudden storm overturned the boat on which he was transporting to Québec a Mohawk prisoner whom the Algonquins planned to execute, with the Iroquois threatening revenge. In death, as in life, Nicolet preserved peace for a time.

Later in the 1640s, two concurrent wars broke out and continued for several decades. The Iroquois wiped out other tribes around the upper Great Lakes, while the Illinois Confederacy almost eliminated the Puans. Descendants of those who survived are today’s Ho Chunks.

Jung stressed that both his new book and The Nicolet Corrigenda: New France Revisited – his earlier publication with Lurie – use words such as “possibility” or “probability,” rather than stating something with absolute surety. (The word “corrigenda” means a list of errors and corrections.) By correcting many of the myths that had for centuries surrounded Nicolet’s time in our part of the world, Jung and Lurie have provided a solid base for further research.

“Not many additional documents from the 17th century are apt to turn up now,” Jung said, “but anthropology is what will yield new information in the future. For centuries, for example, historians believed that Coronado’s tale of a settlement of 20,000 Indians near the Arkansas River in Kansas was a myth. In April 2017, a teenage boy found a cannonball linked to a battle in the area in 1601, and ongoing research and excavation have pinpointed the location of Etzanoa, exactly where Coronado said it was 478 years ago.”

And, closer to home, 59 of the richest archaeological sites in Wisconsin are just north of lakes Winneconne, Poygan and Butte des Morts, about 80 miles from Door County. History is never over.