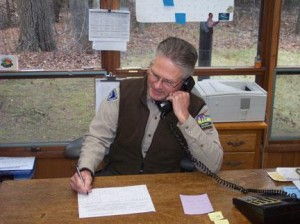

Thomas Blackwood – A Life in the Park

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

“How does a kid from the south side of Milwaukee wind up managing a park in Northern Wisconsin?” Peninsula State Park Superintendent Thomas Blackwood laughed. “For eight years straight I had an uncle who took my cousin and me up north on vacation. Those two week trips were the highlight of my year!”

The seed was planted.

At the end of this month, Blackwood will retire after 30 years of service supervising what many consider the crown jewel of the state’s 63 park, forest, and recreation areas system. As visitors to Wisconsin’s state parks know, Peninsula State Park is the only one with a golf course and a repertory musical theater. It’s one of the few with a lighthouse, especially one that is easily accessible. It has quaint cemeteries, the most popular campsites, certainly one of the favorite beaches in the county and miles of shoreline.

But Blackwood’s uncle didn’t just drop him off in the park in Door County ready for a career; rather, Blackwood’s journey to park management began at Marquette High School, where the quality of his education gained him admission to UW-Madison and a degree in psychology.

The degree was perfect preparation, he joked, for his first job, driving a taxi in Madison.

“As I drove cab I asked myself what I wanted to do with my life,” Blackwood said. While driving taxi, he had taken a photo of a snowy owl that he sold to the Capital Times for five dollars, and the trips to northern Wisconsin were still in the back of his mind.

Jim Zimmerman, who specialized in landscape architecture, offered a field ecology class that met evenings and weekends at the Arboretum, and Blackwood enrolled in the course. Zimmerman, who had “a direct link to Aldo Leopold,” provided the cab driver with “a great inspiration to get involved in natural resources.”

And Blackwood sold a second photo to the Capital Times, one that he took of a Great Horned Owl while following an assignment to observe the nesting cycle of that bird in the Arboretum.

On the basis of his experience in Zimmerman’s class, he applied and was accepted into a master’s program in the Recreation Resource Management program in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences at UW-Madison.

At Wyalusing State Park (near Prairie du Chien, Wis.), Park Superintendent Harry Peterson said to Blackwood, “I have a recommendation that you’d like to be a naturalist.”

Blackwood had never worked as one before, but “it was a wonderful experience,” he said, “and I had my foot in the door!”

That adventure was followed by a stint as a graduate assistant to a professor doing field work in the White Mountain National Forest in New Hampshire, and then later as a ranger at the Apostle Islands State Park where he worked 10 days on and 10 days off.

“I remember sitting on a cliff at the north end of Devil’s Island knowing that I was on the northern most part of Wisconsin, and I had it all to myself on that September evening!” Blackwood said.

Next he worked as a naturalist and ranger at the Effigy Mounds National Monument (McGregor, Iowa), but in the middle of the summer he was offered a place in the Park Superintendent Training Program. First he spent six months at the Kettle Moraine State Forest Southern Unit and then was sent to Peninsula State Park.

In Madison, Blackwood had not only acquired two degrees, but also his wife, Joan. She resigned from her job as guidance counselor at Stoughton High School, and in 1980 they moved to Door County for his training program. In 1982 Blackwood was about to be sent to manage the Red Cedar Bicycle Trail in Menomonie, Wis. when Peninsula State Park Assistant Superintendent Dan Wagner resigned to become a regional park superintendent, and Blackwood was offered the position at Peninsula State Park.

In 1986 Gary Patzke stepped down as the park superintendent, and Blackwood replaced him, becoming the seventh superintendent in the park’s history, now in its 100th year.

The undergraduate degree in psychology has proven useful for Blackwood not only for his time driving a taxi, but also for his career at Peninsula State Park.

“Seventy-five percent of what a park superintendent does is work with people,” he said. He pointed out that parks are for people, and if they don’t come, he and his staff don’t have a job.

The work has been satisfying for Blackwood. He views Peninsula State Park as a gateway.

“Door County has always been a great tourist destination,” he said. “And if you ask visitors what one thing they associate with Door County, they will usually say Peninsula State Park. If you ask people who have built homes here what brought them, many times they will say it was a camping trip to Peninsula Park. This is a gateway park, one that opens people up to the state park system and gets them excited to visit some of the other parks.”

Blackwood is proud of the changes that have taken place in the park during his tenure. One is the addition of a full-time year-round naturalist; oftentimes, those are seasonal positions.

Education is important to him; for a number of years he served on the board for Gibraltar School. Student athletes and physical education students use the park because it is adjacent to the school grounds. Natural science students benefit from an outdoor classroom recently built in the park.

An ecological improvement resulted from the black powder deer hunt, an effective means of controlling that animal population, allowing the regrowth of vegetation and trees.

“When I came here,” he said, “no one had a sense of invasive species.” Now the eradication of garlic mustard, as well as other invasives, has been a major undertaking.

The trail system has been modified to accommodate mountain bikers and skate skiers. The camping reservation system has become automated.

Blossomburg Cemetery is being expanded as an exchange for park ownership of the Gibraltar Township roads within its boundaries. Before the expansion, Blackwood said, purchasing lots at Blossomburg was as difficult as securing season tickets for Packer games!

The park has seen many changes during its century of existence, including the disappearance of a camp for girls, a game farm, and a ski hill. And from an even earlier time, tucked away in the park are the Claflin cemetery, the foundations of pioneer houses, and at Nicolet Bay, evidence of a late Woodland and Oneida Native American culture.

But Blackwood has always operated under a master plan for the park’s response to changing needs. Seventy-five percent of the park will remain a natural area, while 25 percent may be intensely developed. And the goal remains to protect that which is here.

Not long ago Blackwood was honored at a retirement party in Ephraim. In his speech to the group, he asked the guests who had volunteered at the park to stand up. About half of the 120 or so in attendance did, including the Friends of Peninsula Park, the Campground Hosts, and the Nature Center volunteers.

In his honor, some of these volunteers performed songs they had written for him, and conducted a sing-along.

“It was embarrassing,” Blackwood said, “but fun!”

And his daughter Sarah spoke of growing up in the superintendent’s house in Peninsula State Park, telling what an important part of her life it had been.

In 2006 Tom and Joan Blackwood built a new house near Juddville, and they look forward to the next phase of their life in Door County. At this point Blackwood sees his future as a blank slate after January 1. He has agreed to serve on the Town of Gibraltar Planning Commission, but other than that, he is open to whatever may be, perhaps volunteerism or professional work on a limited basis. He and Joan will travel more; she has an affinity for Paris, and both of their adult children live in Minneapolis, Sarah working as a graphic designer and Matt as an attorney.

Blackwood often bikes to work from his new home, and he takes pride in the number of bicyclists he sees in the park. There’s a good chance you’ll still see him on his bike in the park, even after he has moved out of his office.