Is Uber the Missing Piece of Door County’s Public Transit Puzzle?

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

Three or four nights a month, a man in Door County fills his car with bottled water and a jug of candy and drives down to Green Bay. Michael (who requested his last name not be printed) parks on Washington Street or in front of Lambeau Field and turns on the Uber ride-booking app on his phone. At around 4 am, when everyone who needed a ride is safely home, he heads to his favorite $45 motel and goes to sleep with a few hundred dollars in his pocket.

“Why would you want to ride with [a cab driver] as opposed to me in a new car who offers you gum and a bottle of water and has a chat with you?” said Michael.

While still fighting for acceptance in some big cities, ride-booking apps such as Uber and Lyft have changed the dynamic of public transportation. They connect drivers with passengers through a free online platform, often resulting in cheaper fares than private cabs or other forms of public transit.

But that free online platform put $3.5 billion into drivers’ wallets in 2013 and in 2014; Uber claimed to be doubling its revenue every six months.

“With tips, I can pull $320 a night,” said Michael. “Green Bay is just spread out so if somebody needs to go from a hotel down to the airport, fares typically run $8 to $12 per fare. I try to fit in at least five fares an hour so I’m making up to $60 an hour.”

In big cities, where there are always drivers waiting on the street for a constant flow of passengers, the economics of the app complement both the driver and passenger. In Door County, where travel distance can be countywide and a seasonal economy limits the flow of tourists looking for a ride throughout the year, the application of Uber is as unique as it may be important for the future of public transportation on the peninsula.

United Way of Door County first recognized the need for public transportation throughout the peninsula in 2006, when the organization formed a Transportation Steering Committee. For a few years, they surveyed Door County residents on when and where they needed to go.

“We take calls all the time, we’ve done that since we began in 2007,” said Pamela Busch, mobility manager with Door-Tran, the organization that resulted from United Way’s committee. “If we can’t meet the need, we track it… At the beginning a lot of it was, ‘Sorry but we’ll mark it down in case we can meet it next year.’ That’s hard to do because people should have the right to get where they need to go when they want to go and for whatever the reason.”

After a community impact grant from the Door County Community Foundation, federal funding and earning a nonprofit status, Door-Tran began expanding programs. Its first effort was to subsidize travel costs for any Door County resident using other forms of transportation such as private cabs and shuttles.

“If somebody was going to Egg Harbor from Sturgeon Bay and that’s a $30 trip, Door-Tran could pick up $15, dropping the price down to $15 for that person, making it much more affordable,” said Busch.

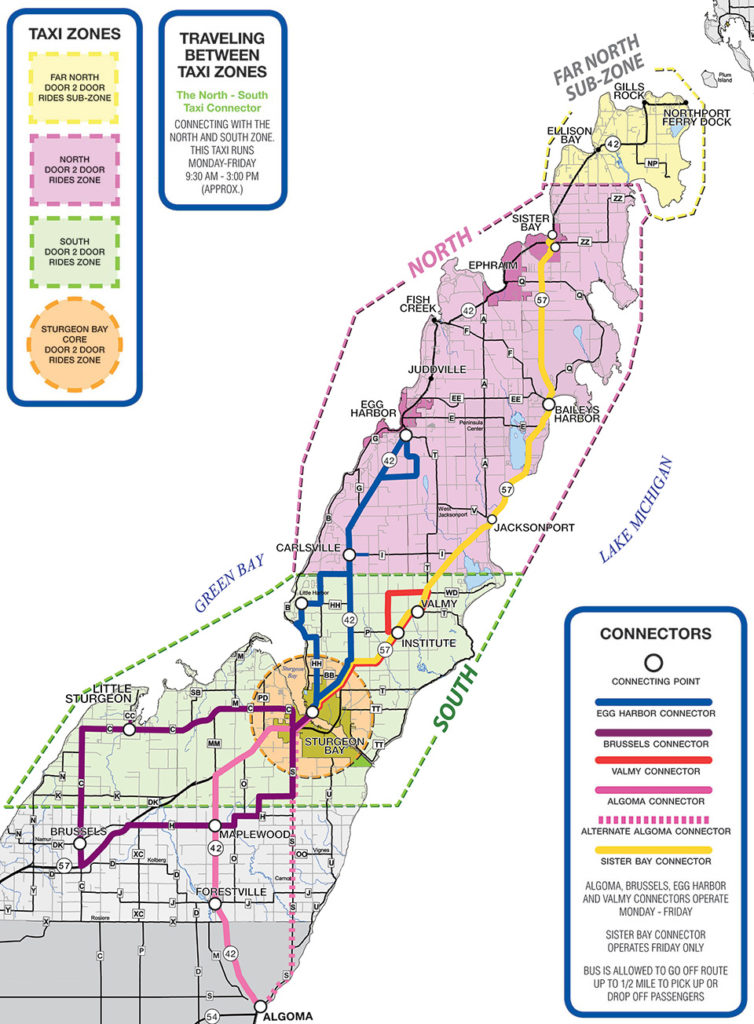

In 2010, using the ride data that Door-Tran collected, the County of Door funded its own public transportation system. Door 2 Door is a shared cab and bus system connecting Sturgeon Bay with communities as far as Sister Bay and Algoma. Although separate from the Door-Tran programming, the two groups work in tandem to provide the services requested from county residents.

“We want to compliment each service but not compete with them and still advocate for each one,” said Busch. “That’s what we have really great in Door County, it’s like all of these partnerships and it’s different than anywhere else.”

“We want to compliment each service but not compete with them and still advocate for each one,” said Busch. “That’s what we have really great in Door County, it’s like all of these partnerships and it’s different than anywhere else.”

Busch referred to partnerships not only with the county but also with the Door County YMCA, Boys and Girls Club and St. Vincent’s Hospital in Green Bay to best schedule rides for those who need them.

Door 2 Door rides operate every day in Sturgeon Bay and Monday through Friday in Northern Door. While offering a vital service to those who need transport for work or medical reasons, the number of riders who use the Northern Door service to simply get around hasn’t seen the growth that Busch is hoping for.

“The bulk of the trips are down in the Sturgeon Bay service area,” said Busch of the county-funded Door 2 Door program, explaining that the Northern Door system averages only 90 rides per month. “If the system doesn’t get any busier in Northern Door and the county does say, ‘We haven’t been increasing ridership and this system down here is overwhelmed’…I would really hate to see that go when Northern Door is where all of the folks who are aging the most are.”

The goal of Door-Tran in collaboration with the county has been to promote the Northern Door system as public transit as opposed to a low-income shuttle service.

But if the county does decide to scale back the Northern Door system, it could open the road for Uber. The ride-booking app has just a few hurdles when applied to a unique place such as Door County.

“Say I’m sitting in Sister Bay with the app on and I get pinged for Fish Creek,” said Michael. “If I’m in Sister Bay, I’ve got to drive 10 to 12 minutes to get them. If they just want to go from the Bayside Tavern to the Gibraltar Grill, I’m going to make $3 and that’s it. I just drove all the way from Sister Bay to go get them.”

There are two main problems that Uber users may face when trying to make money as a driver in the county. Are there enough people looking for rides so that a driver can actually make money? Are there enough drivers spread throughout the peninsula to provide for the passengers in each community, but not too many drivers so that the pool of fares gets diluted?

On Uber’s website, a user is able to get an estimate for how much a fare would cost. The estimated cost for a ride from Sister Bay to Fish Creek is $20. Baileys Harbor to Sturgeon Bay could cost as much as $52. While a flexible schedule to ride whenever you want has its own value, the prices might struggle to compete with the county-subsidized price of the Door 2 Door system.

Drivers know that big cities have enough people to guarantee a profit. But smaller, widespread communities may not be able to provide the volume of riders to encourage more drivers to participate, even on the busiest of summer weekends.

Following big events such as Packer games or concerts, the concept of surge pricing kicks in. When there are more passengers looking for rides than there are drivers in an area, the fares increase to incentivize other drivers to go to that location. While the algorithm for surge pricing is a guarded secret, the rural nature of the county may keep fares high enough if there are not too many drivers.

Michael outlined other hurdles such as the cost of commercial insurance on his vehicle and maintaining his car. He also struggles with the moral questions of not having enough drivers to take people where they want to go.

“What if I take somebody to a bar, how are they going to get home if I go home before they do? I don’t want to take people around because I can’t guarantee I’m going to be available when they need another ride,” said Michael.

But he still has hope that Uber is the next thing for public transportation in the county. Uber has established itself in the greater Green Bay area, which provides the online infrastructure that includes all of Door County.

As the Door 2 Door program north of Sturgeon Bay may need to be revamped in the future, Michael believes that a county subsidy for Uber drivers, just as the county subsidizes Door 2 Door, may be a way to encourage the app to establish itself.

“I’m part of the Young Professionals Network (YPN),” said Michael. “We all know how good it would be for tourism if there were something like Uber up here… With Door 2 Door being county-funded, if the county were to subsidize or have staff that were all drivers and met the qualifications of Uber, why not use what’s already in place?”

In the end, Michael believes it comes down to public education about the program. As more visitors know they can use the service, more drivers may flock to meet that demand, and the demand for public transportation is increasing. Busch said her office is continuing to field calls from local residents about expanding their services and ridership is already on pace to increase in 2016.

Michael views public transportation as an asset to support the vibrant tourism economy that drives most of the industry in Northern Door.

“People come up, they want to go to restaurants, they want to go to bars, but everybody has to drive because it’s the only option. Here they have to always be thinking, ‘Oh gosh I can only have one beer or I can only have one glass of wine’ and it possibly limits their vacation if alcohol is going to be incorporated with it. That’s the biggest thing. Uber would be perfect. It’s truly the future.”

Attempts to contact an Uber representative were unsuccessful.