Washington Island vs. Beaver Island

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

The island off the northern tip of the Door Peninsula was still in its infancy as a community 160 years ago. Small pockets of fishermen were just settling into the area, usually as squatters on land held by absentee owners, and lumbering was just beginning in earnest as steamers became regular features on the Great Lakes. The Town of Washington would finally be formalized in June of 1850 (interestingly at a meeting held on Rock Island) and the population, and economy, of Washington Island would begin to grow in earnest.

While agriculture as a force in the economy was still in the future, fishing became the dominant means of earning a living, with lumbering to supply steamships providing a steady supplement. These were rigorous occupations, but with the fish demand from cities to the south driving up prices, those who applied themselves to the arduous work could earn a healthy living.

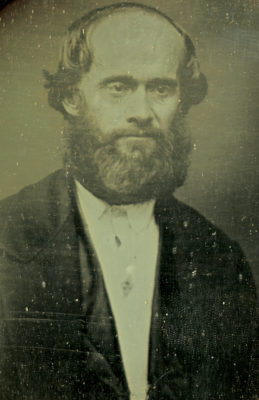

James Strang, prophet of the Beaver Island Mormons. Image courtesy of the Clarke Historical Library, Mount Pleasant, Michigan.

But success bred competition and soon Washington Island fishermen found themselves at odds with a group of Mormons under the leadership of their prophet, James Strang, who started a settlement on Beaver Island, the largest of a chain of islands located in the northern end of Lake Michigan.

The first of the Mormon settlers emigrated from Voree, Wisconsin to Beaver Island during the summer of 1847. That first winter only four families wintered on the island. According to a January 3, 1850 article in the Gospel Herald (the Mormon newspaper published in Voree, which included a regular column devoted to the growing settlement on Beaver Island) the number of families had tripled by 1848 and by the winter of 1849, 50 Mormon families were settled on the island.

The same article goes on to note that the number of steamships stopping at Beaver Island for wood and supplies was just four in 1847, but the number rose to a staggering 62 ships the following year.

In a subsequent article in the same newspaper, dated February 7, 1850, the thriving fishing industry was noted in some detail. While logging and the sale of wood to steamers was an integral part of the island’s economy, fishing quickly became the main economic force. Author Vickie Cleverley Speek notes that the article describes the island’s fisheries as extending “north of the island a full 50 miles, south for 40 miles, and east and west the entire width of Lake Michigan.”

The burgeoning success of the Beaver Island Mormon settlement, combined with the Mormons’ wide-ranging fishing operations, led them to be regarded with significant mistrust among the “Gentiles” (as the Mormons referred to non-Mormon Christians) in the surrounding area. Wild rumors about the Mormons circulated and, in particular, that the infamous “Lake Pirates” were actually the Mormons of Beaver Island.

The “Lake Pirates,” as they became known both locally and in newspapers across what then constituted the United States (The Bedford White River Standard, for example, published a story in October 1855 with the headline “Wholesale Robbery by Pirates on Lake Michigan”), were the blamed culprits for acts of theft and vandalism that occurred throughout upper Lake Michigan and, to a lesser extent, Lake Huron, between 1847 and 1856. Other than a band of outlaws that operated out of the Pine Creek, Michigan, area, no one was certain who these “pirates” were, but in the court of public opinion everyone blamed the Mormons of Beaver Island.

Already blamed for crimes by virtually everyone outside their own congregation, matters took a dramatic turn for the worse when Strang had himself crowned “King” on July 8, 1850. It is a matter of academic dispute whether Strang viewed himself as “king” of the island itself, or whether he was simply confirming his place within his version of Mormonism as the both the spiritual and temporal king of his followers.

Amongst the gentiles of the upper Great Lakes, there was no dispute: Strang and his followers had separated themselves from the United States. In the eyes of his enemies Strang and his followers had committed treason. And the view among Washington Islanders was no different.

As Washington Island historian Conan Eaton noted in his book, Washington Island 1836 – 1876, “Harborites heard that across Lake Michigan on the eighth of July the Mormon Strang had got himself crowned King of Beaver Island. It was bad enough that Strang and his followers hogged the fishing in that region and were probably at the root of most net thieving and such in the northern part of the Lake. But — King!”

In the spring of 1851, United States President Millard Fillmore, responding to allegations of “counterfeiting, robbing the mail, trespass on federal land, and treason,” sent the warship Michigan to arrest Strang and take him to stand trial. Strang willingly surrendered and convinced 31 other male followers to also surrender. After some “judicial hearings” on the ship, Strang and three of his followers were taken to Detroit to stand trial. Ultimately, all four defendants were acquitted, but while Strang was away, relations between the Beaver Island Mormons and the gentiles had grown considerably worse.

As Eaton notes a little later in his history, “…could life really be ‘cosy [sic] and contented’ while King Strang and his Mormons controlled the Beaver Islands? Hadn’t the government hauled Strang and some of his henchmen to Detroit in May and charged them in U.S. District Court with treason, counterfeiting, robbing U.S. mail, and trespass on public lands? Hadn’t the Strangites murdered a non-Mormon fisherman named Tom Bennett in June?”

The “murder” of Tom Bennett, referred to above, stemmed from an attempt by Mormons to serve a warrant on Tom Bennett and his brother, Samuel. According to the Mormon account, the Bennetts retreated to their cabin and fired upon the Mormon constable and his posse. The constable fell with a serious head wound, Tom Bennett was killed, and Samuel Bennett suffered a significant gunshot wound to his hand. Though the Mormons claimed they were legally justified, public opinion — as noted by Eaton — held them squarely in the wrong.

In 1854, the Mormon newspaper The Northern Islander formally announced that polygamy was required by the law of God. The combination of polygamy with boastful claims of the Beaver Island Mormons supplying 20,000 cords of wood annually, selling fish worth $174,000, and reports of 2,608 loyal Strang followers led the Green Bay Advocate to forecast a collision between Strang’s followers and their enemies — “a collision in which the Mormons must fall.”

In November of the same year rumors about a Mormon attacking Washington Island resident John Laframboise with a Bowie knife at West Harbor had island residents raging. Further rumors stated that Mormon boats were just off shore and that several spies had been sent on land to kill Joseph Lobdill (sometimes spelled Lobdell).

The uproar dissipated but Washington Islanders were convinced that Strang’s Mormons were capable of “any outrage at any moment.”

One month earlier the New Albany Daily Ledger, in New Albany, Indiana, reported that the schooner Robert Willis, which had been missing for almost a year on Lake Michigan, “had been captured by Mormons of Beaver Island, her captain and crew massacred, the vessel unloaded and scuttled.” No evidence was ever found to prove the Mormons had anything to do with the disappearance, but no retraction or follow-up story was ever reported.

All the cross accusations and seemingly endless incidents (only a few of which are included in this article) came to an end on the evening of Monday, June 16, 1856, when two men, Thomas Bedford and Alexander Wentworth — both Mormon residents of Beaver Island — ambushed Strang as he walked down the dock between piles of cordwood in St. James Harbor. According to Speek, “One shot struck the king in the left side of his head behind his ear and traveled up through his high-silk hat. As Strang turned to see where the shots were coming from, another shot struck him in the back on the left side, penetrating one of his kidneys. A third bullet glanced off his right cheek bone about an inch under the eye.”

Wentworth raced aboard the U.S. Michigan, which was anchored at the end of the dock. “Bedford,” Speek continues, “took his horse pistol and hammered Strang in the face with the butt until the pistol was broken.” Strang eventually died from his injuries on July 9, 1856, in Burlington, Wisconsin.

News of the Strang shooting spread quickly across the upper Great Lakes and enemies of the Mormons quickly formulated plans to raid the island. Joe Lobdill of Washington Island “easily raised on the island a posse which set out for St. Helena…where a force was gathering for a descent on Beaver,” according to Eaton. This “force” numbered 50 men when they reached Beaver Island, taking seven Mormons hostage before retreating. On July 3 they returned with 150 heavily armed men. By then Strang had been moved from the island, but his remaining “followers — men, women, even babies — were driven from their homes,” according to Eaton, “and herded onto boats with what little possession they could carry.”

Initially, Washington Islanders were pleased with the notoriety their participation in the Beaver Island raids had earned them in papers like the Green Bay Advocate. Headlines like “Posse of about fifty men, mostly collected at the Bay and Washington Island” and “Authorities of Mackinac and Washington Harbor are forcing all Mormons to leave Beaver Island” filled them with a measure of pride.

As reports of the suffering endured by the evicted Mormons began to surface, however, the headlines began to change. In short order the same newspaper featured headlines like “Mormons more sinned against than sinning,” or “The cause of their removal was a mob…from Mackinac and the neighboring islands” left more and more Washington Islanders feeling a sense of shame for the role they had played in the Mormons’ removal.

Whether some of the Mormons on Beaver Island were the infamous “Lake Pirates” remains a mystery. The circumstantial evidence centers on the fact that the thefts and vandalism attributed to the “Lake Pirates” began at roughly the same time the Mormons began establishing their settlement on Beaver Island and largely ended when they were driven from Beaver Island. Nonetheless, it seems likely that most thefts and vandalism were acts of opportunity, perpetrated by gentiles, Mormons, or likely members of both groups, which created a cascade effect where each incident incited an ensuing incident, culminating in acts of misguided violence and a rather tragic end to a difficult period in the history of the upper Great Lakes.

Primary Sources:

Washington Island 1836 – 1876, revised edition, by Conan Bryant Eaton, copyright 1980.

“God Has Made Us A Kingdom, James Strang and the Midwest Mormons,” by Vickie Cleverley Speek, published Signature Books, copyright 2006.

Special thanks to Steve Reiss at the Washington Island Historical Archives for his research assistance, including the various newspaper articles from around the country he located that are quoted/referenced in this article.