A Soldier’s Story: Richard Haney Describes His Father’s WWII Service

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

Had it not been for a series of unfortunate circumstances, his father would never have been drafted during WWII, Dr. Richard Haney told a rapt audience at a recent dinner meeting of the Door County Historical Society.

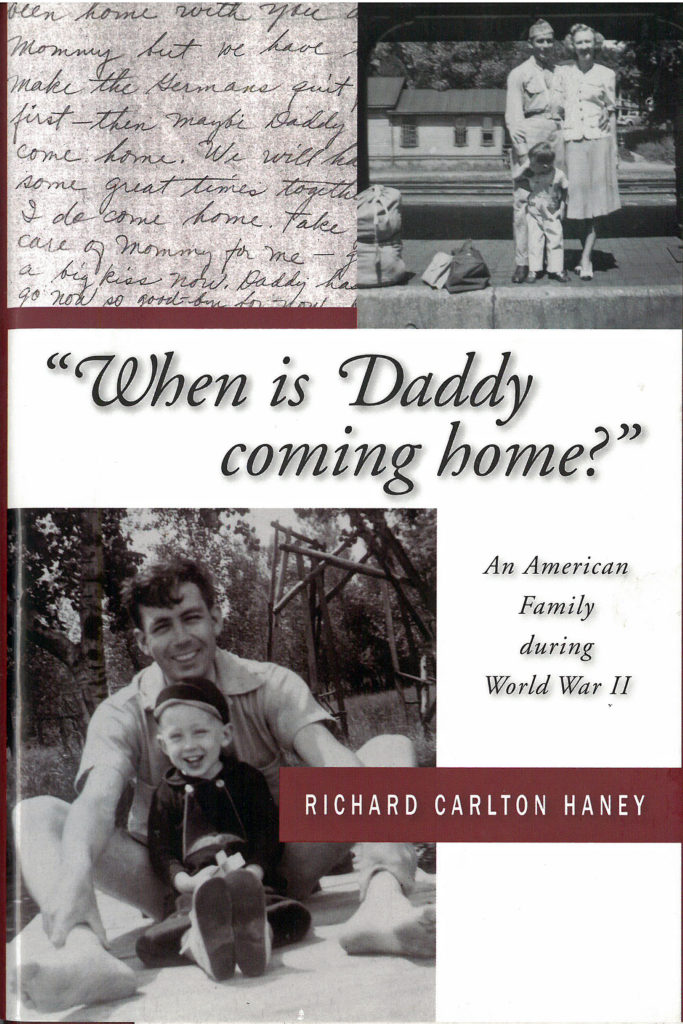

Richard, a retired professor of 20th-century U.S. history, American military history and Wisconsin history at UW-Whitewater, earned his PhD from UW-Madison and later graduated from West Point’s post-PhD military history program and the army’s National Security Seminar at Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania. His book When is Daddy coming home?: An American Family during World War II was published by the Wisconsin Historical Society Press. It details his experience as being one of the more than 183,000 American children whose fathers were killed in WWII.

In 1943, J. Clyde Haney, Richard’s father was the senior district employee of Fox Entertainment Corporation in Janesville, Wis., with an office in the Myers Theater. Through the “bond drives” Clyde organized at the theater – bringing in on various occasions, the U.S. Army Band, five decorated combat veterans and Hollywood personalities – he sold a massive number of war bonds. He also raised more than half of the American Red Cross contributions for Rock County. By the end of WWII, Rock County people and corporations had invested in nearly $55 million in war bonds. Residents of Janesville alone had purchased more than $20 million in bonds, about six months of wages for every man, woman and child in the city.

In 1943, J. Clyde Haney, Richard’s father was the senior district employee of Fox Entertainment Corporation in Janesville, Wis., with an office in the Myers Theater. Through the “bond drives” Clyde organized at the theater – bringing in on various occasions, the U.S. Army Band, five decorated combat veterans and Hollywood personalities – he sold a massive number of war bonds. He also raised more than half of the American Red Cross contributions for Rock County. By the end of WWII, Rock County people and corporations had invested in nearly $55 million in war bonds. Residents of Janesville alone had purchased more than $20 million in bonds, about six months of wages for every man, woman and child in the city.

“Local draft boards,” Richard said, “had a great deal of autonomy. It’s very unlikely that the Rock County Draft Board would have drafted my father, who was doing so much for the war effort on the home front.”

Clyde was not registered in Rock County, but in Dane County, where he had grown up, and he was drafted in February 1944, when the Dane County Draft Board was, as Clyde’s wife Vera said, “scraping the bottom of the barrel” when they called up a 31-year-old husband and father.

Furthermore, the legality of his draft notice hinged on a classification that was changed twice – once too early and once too late to save him. Clyde’s son, Richard, was born in November 1940, 13 months before Pearl Harbor. Pre-Pearl fathers held 3-A exemptions until Selective Service eliminated the classification in October 1943. Two weeks after Clyde received his draft notice, the exemption was reinstated.

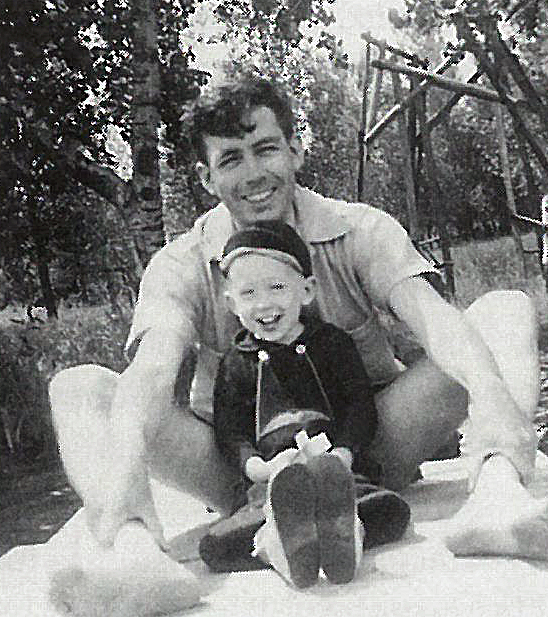

Young Richard Haney with his father, Clyde.

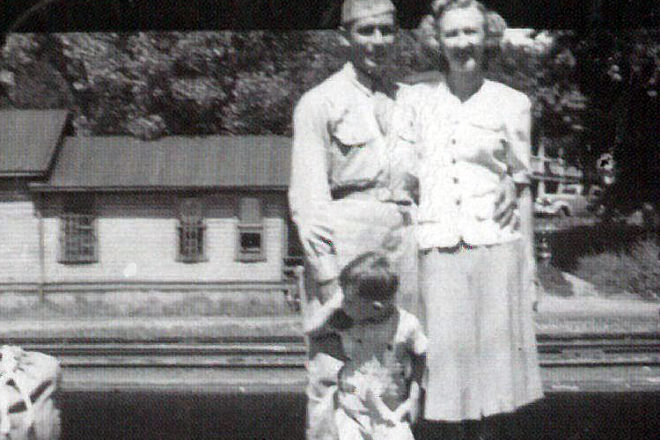

Clyde was ordered to report to the Madison railroad depot at dawn on a raw February morning. Vera went with him, while four-year-old Richard stayed with his maternal grandparents, Mabel and Chauncey Wolferman. After a week at Fort Sheridan, built in 1885 straddling Highland Park, Highwood, and Lake Forest, Ill., the recruits boarded a crowded troop train for an unknown destination.

It turned out to be Camp Blanding, Fla., where 17 weeks of basic training began with a handbook warning: “Our enemies are tough, cruel and highly trained. Their defeat is essential before this world can become a decent place in which to live. Learn your lessons well during your training period and avoid having your mistakes marked by a cross on the battle field.”

Clyde was placed in an advanced intelligence reconnaissance unit, where training was more rigorous and intense than for regular infantry units. He was offered the opportunity to attend Officer Candidate School (OCS), but turned it down “because he did not want the responsibility of giving orders to 25 men,” possibly sending them into deadly situations. Ironically, his son said, that additional training would, at least, have delayed his being sent into combat and likely would have led to an assignment in the states.

Clyde hoped to be sent to Europe, rather than the Pacific, as Janesville had an especially unpleasant association with the Pacific theater. Ninety-nine soldiers and army nurses from the town – The Janesville 99 – had been captured in the Philippines in the spring of 1942 and forced to take part in the infamous Bataan Death March. Only 35 of them survived the march and captivity. When Lt. Marcia Gates finally came home, the experience had been so horrific that it left her unable to speak.

A rumor that made the rounds at Camp Blanding suggesting that pre-Pearl Harbor fathers and 18-year-olds would not be sent overseas proved to be untrue. When Clyde received a two-week “delay-en-route” to visit home on his way to an undisclosed port of embarkation, he knew he was headed overseas, as troops to be stationed in the U.S. had to wait six months for a furlough.

Clyde spent four days riding a train to Janesville. He arrived on June 30, just 24 days after the D-Day invasion on the Normandy coast of France. On D-Day the local radio had started broadcasting war news at 3 am, when it was midmorning on the beaches of France.

Richard remembers those final 13 days with his dad as “idyllic.” When he accompanied his parents to the depot on July 13, he kept eying his dad’s duffle bag, trying to figure out if he could stow away in it. He remembers very distinctly that his father’s last words to him were, “Take good care of Mommy while Daddy is away at the army.” In looking back on that day years later, Vera said that when Clyde left, she was naturally concerned, but never in her wildest imagination did she think that he would be killed and never again return to his family.

At that point, Clyde had no idea where he was headed, but knowing that letters home would be censored, he told his family that any reference to a nonexistent “Uncle Will” would mean he was headed to the east coast and England, while a mention of “Uncle Clyde” would mean the Pacific via the west coast. Eleven days later, he wrote, “I guess it looks like Uncle Will.” On Aug. 2, while still on the ship, he wrote a V-mail letter to Vera in which he made references to sauerkraut, liver and her dad’s swimming pool, which did not exist. The clues, signaling Liverpool and the Germans, successfully slipped by the censors.

Clyde traveled on a Liberty Ship that was double-loaded, meaning there were at least two men for every triple- and quadruple-decker bunk, meaning that they slept in shifts. There was no hot water for showers. England was a welcome change from Florida and the troop ship. Clyde wrote of seeing the famous sights on his first trip to London, but noted that signs for air raid shelters still dotted the city and on many street corners there were sand buckets for putting out fires from incendiary bombs. By the fall of 1944, England had been at war for five years. There was no petrol for private cars, eggs were limited to three a month per person and newspapers were limited to eight pages.

Clyde was also terribly homesick, constantly asking in letters if Butch, his nickname for Richard, missed him a lot. He again had an opportunity to attend OCS and again refused. He volunteered for training as a paratrooper in the hope of staying in England and out of combat a little longer. “Getting home sooner is paramount with me now,” he wrote. Paratrooper training also meant $25 a month more to send home.

Two-thirds of Clyde’s $90 monthly allotment (and his occasional poker winnings) went for rent, utilities and milk, leaving $33 for food and other necessities. To help make ends meet, Vera directed the choir at the Lutheran church, gave weekly private lessons to 27 violin students, worked in the classified ad department of the Janesville Gazette and taught at the Peter Pan Pre-Kindergarten School Richard attended.

On Dec. 19, 1944, Clyde wrote, “I sure hope it’s over before Christmas. It sure would be cause for a joyous celebration.” As Vera was putting the turkey in the oven on Christmas Eve, Clyde was aboard a C-47 on his way to “somewhere in France” with the 17th Airborne Division. Once landed, the men were shipped at night in “deuce and a half” army trucks to the snow and cold of southern Belgium. Attached to Patton’s Third Army, their assignment was to flatten the “Bulge” and defeat the German counteroffensive.

The Battle of the Bulge took place from December 1944 to February 1945. On the night of Jan. 3, the 17th Airborne, including Clyde’s 193rd Glider Infantry Regiment, went into combat, each of them armed only with an M-1 rifle, 200 rounds of ammunition and a few hand grenades. They faced the battle-hardened and elite German First SS Panzer Corps, known for their brutality on the Russian front.

“It was frightening to American soldiers,” Richard writes, “to see the dinosaur-like 54-ton Tiger tanks, with their 88-millimeter guns, and the 50-ton Panther tanks rumbling toward them through the falling snow and fog of the Ardennes Forest.” Wounded men died in the cold unless they were cared for within 30 minutes. Soldiers stuffed newspapers, when they could get them, inside their shirts and clothes for insulation. Clyde was fortunate to have a heavy wool sweater Vera and her parents had sent him for Christmas.

About this time, Vera received a telegram saying that Clyde had been “slightly injured in action.” Not wishing to worry her and assuming that the War Department did not notify families of what he considered “minor injuries,” he wrote a day later from a field hospital where he was being treated for frostbitten feet, not mentioning that he was hospitalized, but asking if she’d received the bracelet he sent her for Christmas. Six days later, he was back in action. He was captured, but soon managed to escape. By February, he wrote that he’d had a shower, the first since he left England 45 days earlier.

Once they heard that the American First Army had breached the Rhine at Remagen, Germany, on March 7, 1945, Clyde and his buddies were more confident that the war would end soon. “I hope that we won’t have to stay over here too long,” he wrote on March 15. Four days later, he wrote his last letter. On the night of March 23, the men were fed steak and apple pie and attended religious services.

The next day, the 17th ABN Waco gliders (called “flying coffins” by the men) were loaded with a pilot and 13 men each. The gliders were constructed mostly of canvas over thin metal support tubes and had wooden floors. Motorless, they were towed by bombers and cargo planes. Their arrival was no surprise to the Germans. On the night before, the Berlin propaganda radio broadcast in English, “Hi, all you good-looking guys in the 17th Airborne Division there in France. We know you’re coming tomorrow and we know where you’re coming – at Wesel.”

When the floor of Clyde’s glider was hit with a shell as it landed, many of the men were wounded. Clyde was hit in the neck. His squad leader wrote to Vera later to say Clyde wasn’t bleeding heavily and was being “fixed up” by a medic when he last saw him. Vera didn’t learn of his death until a telegram arrived 13 days later. The man whose duty it was to deliver the “regret to inform” wires was a close friend of Clyde’s. He sat in his car sobbing after bringing two of Vera’s best friends to deliver the news. Ironically, the letter she wrote to Clyde on Palm Sunday, the day after he died, had expressed hope that the war might be over by April 23, their fifth wedding anniversary.

On April 6, the day after the telegram was delivered, the Janesville Gazette carried a large picture of Clyde on the front page. As he usually did, Richard picked it up from the front door and ran excitedly to tell his mother, “Daddy’s picture is in the newspaper.” Decades later he recalled that she knelt in front of him, gave him a big hug and thanked him for telling her. “I can only imagine,” he wrote, “what raw emotions she must have kept to herself at that moment for my sake.” On April 9, Life magazine published a picture of a soldier bleeding to death beside his crashed glider. Vera recognized her husband, who was wearing the sweater she’d sent him for Christmas.

On April 6, the day after the telegram was delivered, the Janesville Gazette carried a large picture of Clyde on the front page. As he usually did, Richard picked it up from the front door and ran excitedly to tell his mother, “Daddy’s picture is in the newspaper.” Decades later he recalled that she knelt in front of him, gave him a big hug and thanked him for telling her. “I can only imagine,” he wrote, “what raw emotions she must have kept to herself at that moment for my sake.” On April 9, Life magazine published a picture of a soldier bleeding to death beside his crashed glider. Vera recognized her husband, who was wearing the sweater she’d sent him for Christmas.

When Clyde’s personal effects were returned some time later, the most precious things they contained were pictures of Vera and Richard, with Clyde’s bloody fingerprints on the edges. He’d held them as he lay dying.

Clyde and Vera exchanged more than 200 letters during the 14 months he was in service. Many of them are included in When is Daddy coming home?, along with information about Vera and Richard’s life after Clyde’s death and their many visits to the U.S. Military Cemetery near Margraten, Holland, where 8,301 American soldiers lie, facing west toward home.

•••

Letter Number 8,301

For 29 years, Lunette Eichler has taught children ages five to eight at the Hope D. Wall School for special needs children in Aurora, Ill. In 2009, she became the leader of the school’s nine-member Boy Scout troop, with ages 11 to 19. They have spent time learning about the American flag – how to raise, lower and fold it correctly and how to present the colors, which they do at every school event. Most of all, they have learned to love and respect the flag.

They have expanded their study of the flag to honoring veterans who have fought to protect it with thank you letters. The troop receives retired flags from American Legion posts and the Veterans of Foreign Wars. The boys carefully cut out the stars and staple one to each letter. In the past seven years, they have presented about 8,300 letters, many of them going to veterans’ hospitals.

Lunette’s mother, Sherrill Eichler of Baileys Harbor, has presented many of the letters to veterans she meets in Door County, including one to Dr. Richard Haney in honor of his father, who lost his life in WWII. It was letter number 8,301, which happens to be the number of American soldiers buried in the U.S. Military Cemetery near Margraten, Holland – Clyde Haney’s final resting place.