Jon Paul’s Maritime Diaries

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

Wheel and mechanism from the schooner Noquebay in the Apostle Islands. National Park Service Photo.

Over the years working with shipwrecks and artifacts I noticed when examining schooner wheels that they were embossed on the rim with Boston, Massachusetts. This always fascinated me for there were foundries and machine shops in the Great Lakes at the time that had the capability to manufacture these. With so many shipbuilders and shipbuilding at its peak after the Civil War, why would shipbuilders have something so heavy and bulky shipped from the East Coast and not just produced locally? This for many years was one of my “I’ll get to that someday” things of interest.

This spring I set out to creating a standard form of documenting artifacts from around the Great Lakes for use in typology studies. A typology study as defined by Funk & Wagnall is: “1. The study of types, as in system of classification. 2. A set of listings or types.” My project was to examine anchors, windlasses, and other ship implements from the days of sail to learn more about their construction and evolution. What I needed was a good sample study and since I knew that both the Rodgers Street Fishing Village in Two Rivers and the Wisconsin Maritime Museum in Manitowoc both had schooner wheels with mechanisms I thought it would be a good/easy sample study. What I have learned so far is that it was a good study, but it was not as easy as I would have liked.

I started looking for as many of these mechanisms as I could find for the study and found out most of the known recovered units are very close. I decided on six mechanisms from schooners that were built from 1848-1873 all over the Great Lakes. Four of the units are within 100 miles, one is still underwater and one is in Alpena, Michigan (wheel on land, mechanism underwater). So far I have measured and drawn 4 of the units. The wheel underwater is from the shipwreck of the Noquebay in the Apostle Islands that the National Park Service examined and their information was extensive enough to use in the study.

What I have learned so far is that the wheels were not as much of the story as the technology of the mechanisms that actually turned the rudder of the vessel, and it was the inventor Jesse Reed that was at the lead of the story.

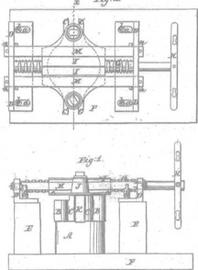

The original 1855 Jesse Reed Patent drawings. The top view shows the unique diamond shaped reversible threads.

Jesse Reed was born in 1778 at North Bridgewater, Plymouth, Massachusetts, in the 1840s and was also known as Col. Reed. Mr. Reed was an inventor and, besides steering mechanisms, he also invented the Reed tool for making cut nails, along with various kinds of pumps, treenail machines, cotton gins, and capstains and windlasses. The History of North Bridgewater, by Bradford Kingman, published 1866, lists 19 patents under his name from 1801 until 1841. His first patent, dated June 9, 1801, was for “Making nails from heated rods” and he would have been 23 years old at the time.

Sometime between 1841 and 1847 he moved to Marshfield, Massachusetts and designed his first steering mechanism titled “Steering Apparatus For Vessels,” which was patented January 26, 1847, No. 4,940 at the age of 69. He would create 5 more designs over the next 11 years. It was his fifth design that was popular in the Great Lakes. Mr. Reed sold his 1855 patent to William P. Hunt, a machinist from Boston. Mr. Hunt refined the mechanism and revised the patent in 1860 and 1861. Of the five studied so far, two were manufactured by Hunt, one was made by the Boston Machine Co, and one was made by Coffin & Woodward Co. Boston.

Mr. Hunt’s machine company on 762 Federal St. was a victim of the 1871 Boston Fire and he probably contracted Boston Machine Co. and Coffin & Woodward Co. to make his wheels and mechanisms, because his patent numbers are stamped into the sleeve of the mechanism, the same way the Hunt wheels are made. This leaves the America wheel, which was also made after the fire. This wheel appears to be a knock off of the Reed design owned by Hunt. The mechanism uses the same two-way diamond shaped threads by Reed but other parts do not match any of the others in the survey. Also, the machining has errors and some of the embossing that listed the address has fallen off of the wheel. It is also the only wheel that lists no patents and the manufacturer is also not listed. Although the embossing is gone, the address “14 Federal St.” is still visible and Boston Mass. still remains on the wheel. At the time of building the schooner America in 1873, the property was leased by O.A. Pinam & Co., which was a foundry.

The original 1855 Jesse Reed Patent drawings. The top view shows the unique diamond shaped reversible threads.

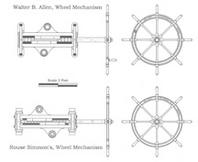

What could be learned from the wheels was nominal. The oldest wheel from the schooner Walter B. Allen built in 1866 had cast iron spokes while all of the other wheels had steel spokes. The cast iron spokes were probably harder to assemble and more fragile. The Allen wheel also had a suicide knob added in the form of a horizontal handle. Both Hunt wheels in the survey are 32” diameter rim; the America wheel had a 36” diameter rim and all of these wheels came from vessels from 123’ to 137’ in length. The Noquebay wheel was 41” in diameter and the Northwest wheel was 43” diameter. These two vessels were 205’ and 223’, respectively. This would lead to the deduction that over 200’ foot vessels required the larger wheels to turn their rudders. The larger wheel would be like a gear reduction. Also, the northwest wheel had ten spokes whereas the rest of the wheels had six.

Drawings of the Walter B. Allen and Rouse Simmons wheels. The Simmons wheel mechanism is the 1861 design. Drawing by Jon Paul Van Harpen.

The Walter B. Allen is the oldest mechanism studied so far and is the closest to the original 1855 design. The Noquebay and Rouse Simmons mechanisms both have the 1860 and 1861 design modifications. The wheel and mechanism that have not been studied yet are those of the Alvin Clark, which was built in 1846. With the help of some friends, I removed the wheel from the Clark in 1993 for her owners. I do remember that this wheel was built in Boston and that it was of the Jesse Reed design. The problem with the Alvin Clark wheel is it has parts from the 1860 design a full fourteen years after she was built. Was this a refitted wheel? Hopefully I’ll find out soon.