Lily Bay: A Village that Lives Only in Memory

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

In the later years of the 19th century, an estimated 85 to 100 people lived and worked in the little community of Lily Bay. There were, at one time, as many as 15 buildings in the village, including a post office, store, sawmill, cooper shop, blacksmith shop, boarding house and several family homes.

During the course of a few years, several industries prospered and vanished, one after another.

Today there are few reminders of what once was, but Clyde “Hap” Smith brought history alive at a recent meeting of the Door County Historical Society at Al Johnson’s Swedish Restaurant. More than 100 participants enjoyed the talk by the professor emeritus from Ohio State University, who was born and raised near Lily Bay and has lived in Sevastopol since his retirement more than 30 years ago.

As elsewhere in Door County, Native Americans were the first to camp around the little creek that comes down through Sevastopol, winds past some springs and ultimately flows into Lake Michigan a short distance north of Sturgeon Bay.

(As a child, Smith found many reminders of those early days in a large “chipping ground” just above the high water mark.)

The white settlers who came later valued the area for the same reasons as the Native Americans – water, good hunting and the forests to provide wood and protection on the west. One of the first things they did was to build a pier. In those days, piers were a third- to a half-mile long, with an area at the end large enough to turn around a horse-drawn wagon. The creek was dammed to raise the water level five feet to facilitate getting logs out.

For many years, until the ship canal opened in 1882, the pier at Lily Bay was Sturgeon Bay’s major port – an excellent site in the summer and one of the last bays to freeze in the winter.

Joseph Smith – often called “The Cedar King of Door County” – was the first lumber baron to establish a business in the area. In 1879, he shipped 70 cargos of cedar worth about $150,000. In fact, what later became Lily Bay was first named St. Joseph in his honor. (The name that came later and endured was apparently chosen to honor the daughter of Smith’s partner, William H. Horn.)

Victor Mashek, a Kewaunee banker who also owned a fleet of schooners, became interested in the area and in 1883 bought out Smith’s share of the lumber business. He planned to continue the partnership with Horn, but it is reported to have survived only 15 days. Mashek purchased 2,000 acres of timber land in the area of Lily Bay and another 2,000 acres near Clark Lake and built a shingle mill in Lily Bay.

Mashek, who had visions of Lily Bay becoming a thriving suburb of Sturgeon Bay, often sailed from Kewaunee to keep an eye on his business ventures, one of which brought about a major change in the lumber industry. He had crews of 40 men in the woods cutting hemlock trees and stripping the bark, which was shipped to Chicago to be used in tanning hides. While the hemlock logs had previously been left to rot in the forest, they were now turned into railroad ties, for which there was a booming market in the Midwest.

Mashek’s logging crews worked throughout the cold months, with sawmill crews arriving in the spring. The log-sawing men earned $50 a month; the cook, $25; and woodchoppers, $15-$20.

The system worked well for a half-dozen years or so, until most of the trees in the Lily Bay area had been cut. This was hastened by the development of the “rake,” an addition to the crosscut saws that had replaced axes for felling trees. While the horizontal saws were a definite improvement, sawdust quickly filled the cut, causing the saw to jam and slowing the process. The rake, with a short tooth added to the saw, kept the cut sawdust free. Trees came down faster, but this meant an earlier end to lumbering in the area.

In 1893, Mashek moved his operation to Whitefish Bay, where there were more forests to fell, and Lily Bay lost its heart and soul. Hap Smith noted the change was almost immediately apparent in newspaper ads for Lily Bay’s general store. Once they had featured products from the sawmill. Now, it was men’s and women’s clothing and household goods.

With lumbering over, Lily Bay men turned full time to fishing, an industry that had shared the pier for a long while. They did well for a number of years with herring and whitefish. In the days before refrigeration, herring was pickled, and a cooper’s shop was needed to produce the 55 to 60 barrels shipped out each year to Cleveland, Chicago and Kansas City. Later, when refrigeration became available, the production of barrels switched to wooden boxes for frozen fish.

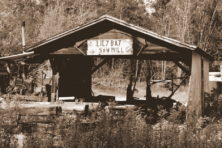

For so long, Lily Bay was able to adapt to the changing needs of the business world, but eventually it came to an end. All that remains today is the Lily Bay Sawmill (the former cooper shop) and the old Wester’s Fish House, now a private residence.

There is also a more recent reminder of the village that used to be. In 1987, John and Eva Groenfeldt donated an acre of land on Lake Michigan to Door County, and it became Lily Bay Park, the smallest of the county’s parks. It’s located on County T, just before it merges with Glidden Drive, straddling the town line between Sturgeon Bay and Sevastopol. There’s a bit of parking and a fair-weather boat launch on a 150-foot sandy beach.