‘TALLAK! immigrant’: A Book for Everyone with Ancestors

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

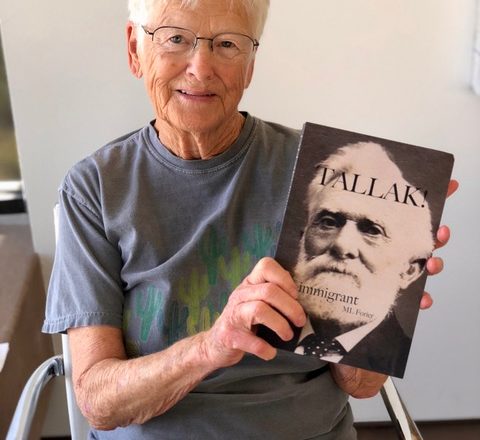

It was the cemetery, finally, that brought it full circle. ML Forier had devoted 23 years to researching the history of her family, starting with her great-grandparents, Tallak Tellifsen Høen and Ellen Karine Halvorsdatter Høen, who left Norway for America in the mid-1840s.

Forier is the youngest daughter of the youngest daughter of the youngest son of Tallak and Ellen. The epiphany that inspired her to complete the book she’d begun decades before occurred on a Hainesville hilltop in 2013 when her two-year-old granddaughter, Kaera Elizabeth Forier, was laid to rest next to ML Forier’s brother, who died at age 11, and near Kaera’s great-great-great-grandparents and all the generations of family between them.

The book, TALLAK! immigrant, that grew out of that day is dedicated to that little girl and her ancestors. The dedication page also includes a quote from Of Time and Place by Richard Quinney: “Our lives continue – in body, mind and spirit – from their lives. In this real sense, there is no birth and no death. There is only the one river of life that keeps flowing, and we are all part of it. We know that our ancestors are not merely of a former time. They are with us always, in our daily lives, just as we will be in the lives of those who come after us.”

“I was nine,” Forier writes, “the day my parents dropped me into my past.” For the rest of her childhood, she lived with her grandmother, Carrie, for a few weeks each summer, “in a time before mine.” She became familiar with the Sears catalog in the outhouse, learned to prime the pump, gathered the cows for milking, cleaned the chimney, lit the lamp and baked biscuits in a wood stove.

A few years later, Forier learned of the stories and family history that her grandmother had written, covering the century from 1846 to 1946. Cousins, she discovered, had prepared a genealogy chart reaching back to 1750. Finally, all the history was too much to ignore.

“I wanted to see and feel and smell the life of my great-grandparents,” Forier said. “Those who began this tribe of Haineses and all its offshoots. I wanted to see them as clearly as my glimpse of my grandmother’s life when I was nine.

“And I wrote. I wrote my story. And yours.” Because TALLAK! immigrant is not just the history of the Høen/Haines family. “My story is your story,” Forier says. “It’s part 19th-century travelogue, part ‘how-to manual’ to unearth the lives of my ancestors – and yours.”

She gave three talks during a long weekend when she was here to visit family in southern Door County and to introduce her book. At the Sturgeon Bay Library, she spoke about effective methods for genealogical research; at Hanson House – during a presentation sponsored by the Door County Historical Society – she talked about her ancestors’ history; and at Novel Bay Booksellers, she read from her book.

Perhaps if any of us looked at the years between our great-grandparents and ourselves, we’d find amazing stories, too. Or perhaps Forier was just fortunate to have unusually interesting ancestors. TALLAK! immigrant, she says, was written in the genre of creative fiction, reflecting everything known about the events described and adding plausible details about what could have been. Lived or created, it is a fascinating tale.

The official Norwegian Church opposed emigration, considering it the work of the devil, but times were hard in that land-poor area. That’s why Tallak; Ellen; their son, Oliver (Halvor); Ellen’s mother, Marte; and her five other adult children – Elias, Jens, Ole, Kirsten and Nella – spent a year preparing for their two-month journey across the Atlantic.

The barque would provide three potter (about three quarts) of water for each passenger per day. In addition, every adult was required to take with them kitchen utensils and provisions for 10 weeks: “70 pounds of bread, 8 pounds of butter, 24 pounds of meat, 10 pounds of pork, 1 keg of herring, 3/8 barrel of potatoes, 20 pounds of rye or barley flour, ½ skjeppe (about 1/4 barrel) peas, ½ skjeppe pearled barley, 3 pounds of coffee, 3 pounds of sugar, 2½ pounds of syrup, and a little salt, pepper, vinegar, and onions.”

So they prepared for eight adults and little Oliver. But just a month before the extended family left Norway, Elias married Berthe Marie Hendriksdatter. A dilemma ensued: Should the others share their stored-up provisions, or should Berthe take her own food? All we know is that she walked off the ship in New York on Elias’ arm on Aug. 14, 1846, and was never mentioned again in the family records.

There was a two-year detour to Canada, where Nella became engaged to Isaac Chase (but failed to join his Quaker meeting because it was suggested that the Lord might not approve of the rose on her bonnet). In 1848, Ole settled in Port Huron, Michigan, while the rest of the family – which by then included Tellif Tallaksen, Tallak and Ellen’s second son – made their way to Port Ulio in the brand-new state of Wisconsin.

Within two years, Tallak had purchased more than 400 acres in the heart of Port Ulio for $950. Kirsten married Soren Anderson; Elias – with Berthe assumed dead – married again; and Jens married and moved to Star Prairie. Ellen bore three more children – Melvin, Marie and Eli – in Port Ulio.

With the rest of the family permanently settled, Tallak, Ellen and their five children headed north 100 miles with a covered wagon pulled by oxen filled with their possessions. (No seats, like in the movies.) On a good day, they traveled 10 miles on the rough trail through the forest to Green Bay. After a year or so, they moved to Sugar Creek (not a town, just a creek called Sugar), where Christine was born in 1857.

Tallak purchased 122-36/100 acres of land here (now the town of Union) for $152.95, with the deed signed by President James Buchanan. They were the first white settlers here. And, according to historian Hjalmar Holand, Tallak became a trader with the Native Americans, exchanging “glittery trinkets” for horses.

A year earlier, though, he had paid $1,100 to Marcus Bockman for 100 acres of land on Big Creek in Sturgeon Bay. Coincidentally, it adjoined the Hanson property, in whose home Forier spoke about Tallak’s family 163 years later. But they never moved to that piece of land. Close to Sugar Creek was Little Sturgeon – the oldest and most prosperous settlement in the county – with a sawmill, grist mill and general store. Not even a general store had yet appeared in rough-and-tumble Sturgeon Bay.

The Høens’ seventh child, Oscar, was born on Aug. 19, 1860. He would become the grandfather of ML Forier and the husband of her beloved grandmother, Carrie, who introduced nine-year-old Forier to a life before her time.

We’ll leave them at this point. Read the book to learn the family’s adventures for another 46 years in Door County, until the death of Tallak Haines (the name was finally Americanized) at age 93. According to a local newspaper, he was believed to be the oldest man in Door County.

TALLAK! immigrant is available in Sturgeon Bay at Novel Bay Booksellers, the Door County Historical Museum and Green General Store at Heritage Village at Crossroads at Big Creek. Kindle and paperback versions are also available from Amazon.