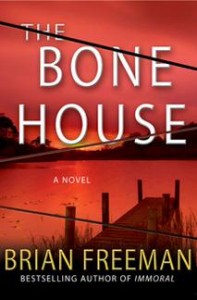

The Bone House

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

EXCERPT

The Bone House

By Brian Freeman

St. Martin’s Press, 2011

Water pummeled Troy. Water was everywhere.

The twenty-footer clawed into the waves, but beyond the top of the peninsula, the boat rocked like a toy in the ocean. The headwind bit at his exposed skin, and the sky gushed rain down as heavy as a waterfall. He stayed west beyond the worst currents of the passage, but even in the calm of Green Bay, swells rose up and slammed the boat down so hard that his jaw hurt as the bow landed. His progress was excruciatingly slow. After ten minutes, he thought he’d spent an hour on the bay.

He was cold to his bones. He wore long underwear under his jeans and a heavy wool sweater over his jersey, and he was covered head to toe in oilskin camouflage gear he’d borrowed from his father’s closet. None of it kept him warm. His toes were numb inside his boots, and he clutched the wheel so hard he couldn’t feel his fingers. Beads of rain squeezed inside through the gaps at his collar and trailed down his back like icy fingers.

The black sky felt as opaque as night. He had to keep wiping his eyes to see the land looming on the horizon ahead of him, seemingly as far away as when he’d started. To his northeast, the Plum Island lighthouse blinked out of the gloom. With every minute, he thought about turning back, but if he did that, he would prove what his father had always said about him. He was a failure. A coward. If Glory was looking down at him in the middle of the water, he didn’t want her thinking he’d abandoned her.

Troy churned through the passage. He fought to keep the nose pointed toward the bulk of the island as the current swept him nearly in circles. The up-and-down hammering made a relentless thump, vibrating through his body. Even his breathing felt strained as rain flooded his nose and mouth. He had to cover his face and swallow air open-mouthed to keep from choking. As bad as it was, he barely noticed when the water finally grew steadier around him. The boat picked up speed. When he glanced eastward, he realized that Plum Island was behind him now. The land mass of Detroit Island, which stretched like a finger below Washington Island, acted like a reef to cut the chop from the lake.

His adrenaline soared. He’d survived the worst of the crossing. The island grew large less than two miles ahead of him.

As he neared land, Troy stayed west of the main harbor where the ferries came and went. He didn’t want to be spotted there. He hugged the shore and turned north along the island’s jutting index finger, where he could make out individual trees, the white paint of houses built on the water, and deserted beaches. Ahead of him, near the rounded end of the finger, the green trees stopped at the water’s edge, and the vast bay took over, reaching twenty-five miles to Michigan’s upper peninsula coast.

He followed the land as it turned back south into the deep inlet in the island’s coast known as Washington Harbor. A long white beach tracked the water. The base of the inlet was known as Schoolhouse Beach, made not of sand but of millions of ivory rocks polished smooth by the currents. He’d gone there with Glory many times in the summers. If he looked hard enough, he could picture her there, in her bikini on a red beach towel, or skinny-dipping in the cool water on a late weekday afternoon. None of that mattered now. What mattered was that Mark Bradley lived on the east side of the beach, in a house hidden inside the trees.

Troy aimed for a forested stretch of shore, out of view of any of the beachfront houses. Most were unoccupied now anyway. Looking down, he saw the water growing shallow. He raised the motor and drifted. As he neared the beach, he climbed over the side and dropped into the knee-deep water, which knifed him with cold. He splashed onto the rocks, dragging the boat with him, until it was far enough out of the water that it was too heavy to move. He left it there. He wasn’t sure if he’d go back for it or if he’d slip onto the ferry in the morning with Keith’s help.

With any luck, no one would have discovered Mark Bradley’s body by then. He’d be free to escape back to the mainland.