The Grand Traverse Islands – Worthy of National Lakeshore Designation

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

In 1930 the boosters of Bayfield, Wis., invited a representative of the National Park Service to determine whether the Apostle Islands were suitable for designation as a national park. The man, Harlan Kelsey, took one look at the clear-cut, burned out islands and said, “Absolutely not. They will never be worthy of the National Park Service.”

Many people gave up hope. Yet 40 years later, despite Harlan’s dismissal, the Apostle Islands did become a national lakeshore, and Americans have been enjoying their great natural beauty and mystery ever since.

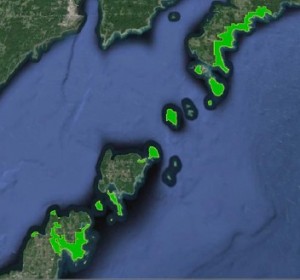

The Grand Traverse Islands, connecting northern Door County to Michigan’s Garden Peninsula, are the next Apostle Islands – or should be.

The island chain is rich in biodiversity and cultural significance. Part of the vast Niagara Escarpment, stretching all the way to Niagara Falls, the islands consist of dolomitic limestone rock formed more than 425 million years ago from compressed coral reefs along the shores of a warm, shallow sea. Rare wildflowers and orchids found almost nowhere else on earth call them home; songbirds, bats and butterflies return to them every summer; lake fish spawn in their shallows by the thousands; and monuments to our maritime history command their shores.

They were given their name by early French voyageurs paddling from one peninsula to the other on their long and difficult journeys, and they encompass five 19th century lighthouses, a former U.S. Life Saving Service Station, numerous shipwrecks, Native American archaeological sites, and the great estate of Chester Thordarson.

The islands were identified for protection as far back as 1967, when the U.S. Bureau of Outdoor Recreation conducted an unofficial study of the islands and recommended that they be turned into an “interstate wilderness park” – a recommendation that was later enthroned in the Bureau’s landmark 1970 Islands of America report. On the heels of that recommendation, Wisconsin and Michigan began jointly planning the interstate park’s creation. Wisconsin went as far as to commission an environmental impact study of the Grand Traverse Islands State Park in 1978, and purchased five small plots of land on Detroit Island for inclusion into the park shortly thereafter. (The plots are still owned by the Wisconsin DNR to this day and remain on the books as an official state park.)

Sadly, either because of decreasing state coffers or the changing politics of the 1980s, the interstate park plan was abandoned. The islands have remained largely inaccessible to the public and the lighthouses and other historic buildings have been left to decay. Many are now among the nation’s most endangered maritime structures. This is a national tragedy.

The time to act on the Grand Traverse Islands has come, and the answer is a national lakeshore. The area would be most effectively managed by a single agency, and since the archipelago bridges the states of Wisconsin and Michigan, any single overseeing agency must be federal. The National Park Service (NPS) is a perfect candidate. Although the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service does a fantastic job of managing the lands it oversees and is working with the Friends of Plum and Pilot Islands to open Plum Island up to the public, its primary goals do not typically include historic preservation and interpretation, which is greatly needed throughout the Grand Traverse Islands. The NPS has that interpretive mission, and would allow for greater public access.

Moreover, national parks generate huge economic benefits. According to a recently released National Park Service report, the national park system brought $14.7 billion in spending to gateway communities in 2012. With 401 National Park Service units, that is an average of more than $36.6 million dollars per park unit!

The process for creating a national lakeshore is neither easy nor straightforward. It would require an act of Congress or an executive order from the president, both of which can only be issued following an affirmative special resource study (SRS) of the area in question by the NPS. And the NPS can only conduct an SRS if it is authorized by Congress to do so.

With that in mind, I’m sending a proposal to Congress and requesting that they authorize an SRS. My hope is that by reigniting the conversation, I can keep the idea alive, and that one day – even if many years from now – the dream of a Grand Traverse Islands National Lakeshore might be realized.

You can view John’s proposal for a National Lakeshore at grandtraverseislands.com.