Wheelin’ to Manhood

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

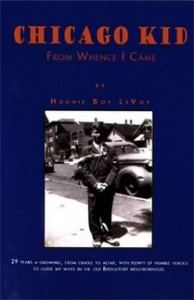

Excerpt from Chicago Kid: From Whence I Came

There was only one rite of passage left for me on Thursday, February 18, 1959 at 8:52 am when I reached the legal age of 21. Whereas, yesterday on the 17th and up to the early morning on the 18th, I was just “Hughie Boy” or “kiddo,” or better yet, “young man.” Now I was to be known as “man,” “Mister,” “Sir.”

I had passed the first rite of manhood in Chicago 10 years earlier when I lit and smoked my first cigarette in our underground sidewalk clubhouse. In the years afterward, I moved from sneakin’ a smoke in the alley, to smoking at home and flicking the ashes in to the ashtray on the front room drum table. Then I graduated from puffin’ on Lucky Strikes to inhaling Winstons – the filter was saving my lungs, the tobacco company said. I even tried cigars at weddings or when a baby was born.

I had no trouble hurdling the second rite of maleness, playin’ sports. I was proficient in football, basketball, bowling, and annual love of my life, baseball. I could run, through and catch the pigskin, dribble the basketball down the court, hit the softball hard and far, and compete to win the game. And although I had usually suffered rejection at being picked last or “left out” for the softball game as the littlest kid on the block, everyone agreed that by the age of 21, I not only could play these games, but also talk about sports. “He shudda bunted instead of swingin’ away,” I second-guessed the White Sox manager after the batter failed to advance the runner on first.

Just recently I had overcome the third rite of male maturity. I had learned the hard way with a nasty bump on my forehead, to always eat well before going to a party. Then I took the advice of a veteran Chi-Annie who said, “Always count.” He admonished me, wagging his right index finger in front of my face.

“One drink – mixed of course. Then maybe after a half-hour, a second drink – still mixed. Talk again, laugh, dance, sip instead of drinkin’. Walk to the toilet. Have some chips or popcorn. More dancin’. A little sweat – that’s good! Gets rid of the poison. And no straight stuff. Don’t put any whiskey in your mouth that’s so powerful it causes barroom floors to leap up and hit yuh in the face. Okay! After an hour or so, maybe a third drink, but that’s the limit. Three’s yer lucky number. And make sure its got lots of ice and 7-up. Ya wanna really nurse this one. Remember! Remember! Ya wanna be around at the end of the night to take that girl with the brown eyes, you’ve been dancin’ with, home. Got it?”

Three minutes of lost innocence and two bucks took care of the fourth rite. It was late one cool evening in 1958 when an older Chi-Annie and I drove to 14th Street, east of Jew town. He knew the street and the old, frame house in the middle of the block with the red light in the window.

Bet there was still one rite of passage I had not conquered. One acquisition that would gain the respect of my peers, the pride of my father, and interest of the opposite sex.

No, it wasn’t a job or career. I had been workin’ since the age of nine, fifth grade all the way through high school, and now at the Santa Fe Railroad. There was no glory or great sense of manhood in me with work, even though my father had taught me that an honest man gets his hands dirty at work: the manual labor on the docks after high school, and subsequent savings for college were all directed to get a job where I didn’t get my hands dirty.

And it certainly wasn’t a gun that I needed to be called a man. My father took me hunting for pheasant one Saturday when I was eight years old. We were walking through a corn field south of Chicago, as he explained to me about gun safety. I watched as he showed me how to carry the 12-gauge shotgun with the double barrels disengaged from the gun stock and triggers.

All of a sudden our noise spooked a pheasant to fly up in front of us. I looked with wide eyes as Daddy grabbed the double barrels with his left hand, locked them in place with the stock, raised the loaded shotgun, and pulled on trigger, “BAM,” then they second, “BAM.” But it was too late! The pheasant flew up and away. Still alive.

The shotgun blasts scared the H— outta me. And the thought of killing a brightly colored bird with a long pointed tail and ringed-neck, turned me off too. Besides, what was there to eat on a pheasant anyway?

I had no trouble at all the with BB gun Daddy got for my brother and me for Christmas when I was nine. “No birds,” he warmed us when we were practicing with it in the back yard against a cardboard target.

One day Patrick and I spotted a rat crawling on the old wood Daddy had stored between the porch joists under Grandma Bosak’s back porch. We quickly blocked one end of the porch joist space with a wide piece of wood. Then we ran to the other end with the gun. We could see that the rat was confused now because he didn’t know which way to crawl, with one end blocked and Pat and I at the other.

“PUNF” went the gun when my brother fired at the rat. “Darn it, I missed ‘em,” he said to me.

“Lemme try,” I said, grabbing the gun and cocking it. I looked down the 15 feet of old wood that was like a tunnel and spotted that rat lookin’ at me. I aimed by closing the left eye, sighting the barrel with my right. Then I slowly squeezed the trigger and held the gun firmly.

“PUNF”

“I hit ‘em,” I yelled to Pat.

My brother looked into the tunnel and could see the rat bleeding from the body and started to crawl away from us toward the blocked end.

“PUNF” came the sound again. “You dirty rat, take that,” Pat was yellin’. He cocked the BB gun again and fired. “PUNF.” And again he cocked, “PUNF.” Again, “PUNF.” Beebees were flyin’ all over that tunnel of death.

None of the Chi-Annies ever talked much about having a pistol, or rifle, shotgun, or even going’ huntin’. It just wasn’t part of being a man, as far as I could see. Even the older guys who had been in the Army never had much to say about guns.

However, one Saturday afternoon, a bunch of us were takin’ it easy at the Club, watchin’ a White Sox daygame against the Orioles. Paul Richards, the manager of the GOGO SOX in the early ‘50s was now the skpper of the Baltimore team. As usual the Sox were chasing the Yankees for first place that summer.

Into the Club walked Jimmy, one of the older neighborhood guys who liked guns. He came over to show us his new, aluminum ’38 caliber handgun he had just got that week. The bunch of us stood around the front room as he was tossin’ it from one hand to another. Then he took it in his right hand, put his finger on the trigger, and started pointing the gun towards us, wheelin’ in a circle, making a prolonged “Whee” sound.

When Jimmy came to me, he stopped, smiled devilishly, said something like “Russian Roulette,” and started to pull the trigger.

I yelled “NO,” but it was too late.

“Click” I heard, mingled with my terror of staring at the barrel of that gun.

He laughed and me, and said, “Don’t worry, there’s no bullets in it. See.” He pulled the bullet chamber down. Sitting in the top slot, with its firing cap exposed, next up in the barrel was a lone bullet.

Naw, my final rite of passage had nothing to do with guns, no matter which end of the barrel I was on. And it had nothing to do with the violence and victory of a fist-fight. By the late ‘50s, boxing had lost much of its glamour and toughness. Besides, I had already proved myself with the fists in a one-round tiff against another Jimmy four years earlier, after being “egged on” by the guys.

Like most things American, there were choices if I crawled and clawed my way up to the last plateau of masculinity. I had to decide. Decide between makes, models, colors, standard or whitewall tires. “Are you a Ford man, a Chevy guy, or maybe a classy Chrysler gent? 2-doors. 4-doors. Hey, how about a nice convertible! Black with chrome is really tough-lookin’. Classy! Stay away from red or yellow. Sissy colors! White always shows the dirt and grease from the street. And lissen! Get the stick on the steerin’ column. There’s nuttin in yer way when yer parked at the Lake. Ya know what I mean?”

With the connection of my girlfriend with the brown eyes and dark hair whose uncle had a Mercury dealership in the northwest suburbs, and the advice of my father who had been kickin’ tires since the ‘20s, I bought a ’51 Chevy. It had a fantastic black paint job, flashy chrome, whitewalls, and a sweep-back 2-door styling. And the stick was on the steering column. Looked just like the Batmobile. What a sharp car!

I was now ready to conquer the world, my passage to manhood was complete. I even got my father to call me Hughie instead of Hughie Boy.

Chicago Kid: From Whence I Came, a new memoir by Door County resident Hughie Boy LeVoy, is now available.

The book contains a series of personal scenes over 20 years, spanning birth to marriage. There are poignant moments with delivering papers, rooting for the White Sox, meeting girls, working on a freight dock, and the turmoil of choosing and following a career.

To read LeVoy’s motivation for writing Chicago Kid and to read a seven-page excerpt of the book, visit http://www.xlibris.com/CHICAGOKID.html.

Hard covers of the book are available for $29.99 plus tax; paperbacks are available for $19.99 plus tax. $2 from every book sale will be donated to the Jim Larsen Boys & Girls Club of Door County.

For more information or to order a copy call 920.854.4919 or email [email protected].