Getting Connected: Unlikely Group Brought Internet to Northern Door County

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

Since the dawn of the internet era, smart minds have struggled to entice the nation’s largest communications companies to improve connections on the infrastructure dead end that is Door County. Over and over again, they have bypassed our rural outposts, while much-ballyhooed projects to do it with public help have proven little more than pipe dreams.

But in the early 1990s, thanks to an unlikely confluence of minds – a librarian, an introverted computer geek, a tourism promoter, and a consultant with a tech obsession who wanted out of the city – Door County carved out a spot at the forefront of education and tourism technology. Here is how it happened.

* * *

Miriam Erickson always kept an eye on the future.

“It probably came from my father,” she said. “I grew up on a farm, but we were a progressive family. My father was always learning, always taking classes at the University of Wisconsin-Extension.”

Erickson came to Gibraltar School in 1960 as a home economics teacher, but by the early 1970s she could see that the subject was going to be phased out. If she wanted to have a job, she needed new skills and a new specialty, so for two summers she spent weekdays at UW-Milwaukee, earning her Masters in Library Science in 1974.

“I always loved books, loved learning, so it seemed natural,” she said.

Erickson returned to Gibraltar as the librarian, commanding the room from behind delicate eyeglasses, but tough as a football coach. She would become the unwavering force that drove Gibraltar into the connected age, and in 1979 succeeded in getting a terminal installed that connected Gibraltar to the library at UW-Green Bay (UWGB).

Not all of her teaching colleagues shared her enthusiasm. Some feared technology would carve away at their jobs, refusing to even use a computer. At least one administrator scoffed at the costs associated with the new technology, and many parents in the community said what parents of every generation say when education changes, “Well, we learned just fine without that stuff.”

When budgets were particularly tight in the 1980s the school created a committee that examined expenses line by line and determined the terminal and other technology was a luxury. One administrator came into Erickson’s library and called the computers “just toys,” but Erickson didn’t dwell on the naysayers.

“I knew this technology was the way things were going, and my philosophy was to work with the people who were positive and wanted to move ahead,” she says. “I wanted to be on par with the school districts in Neenah, Appleton, and the best schools in the region.”

Erickson didn’t know the ins and outs of how the terminal and computer networks functioned, but it turned out it was better that she didn’t. It didn’t bother her that her students’ knowledge surpassed her own, and throughout the 1980s her students ran much of the school’s network. One of those students was a self-described “introverted computer geek” named Greg Swain.

* * *

Swain spent hours of his high school years in front of a screen, tinkering, figuring out how the bulky machines worked, and dabbling in programming.

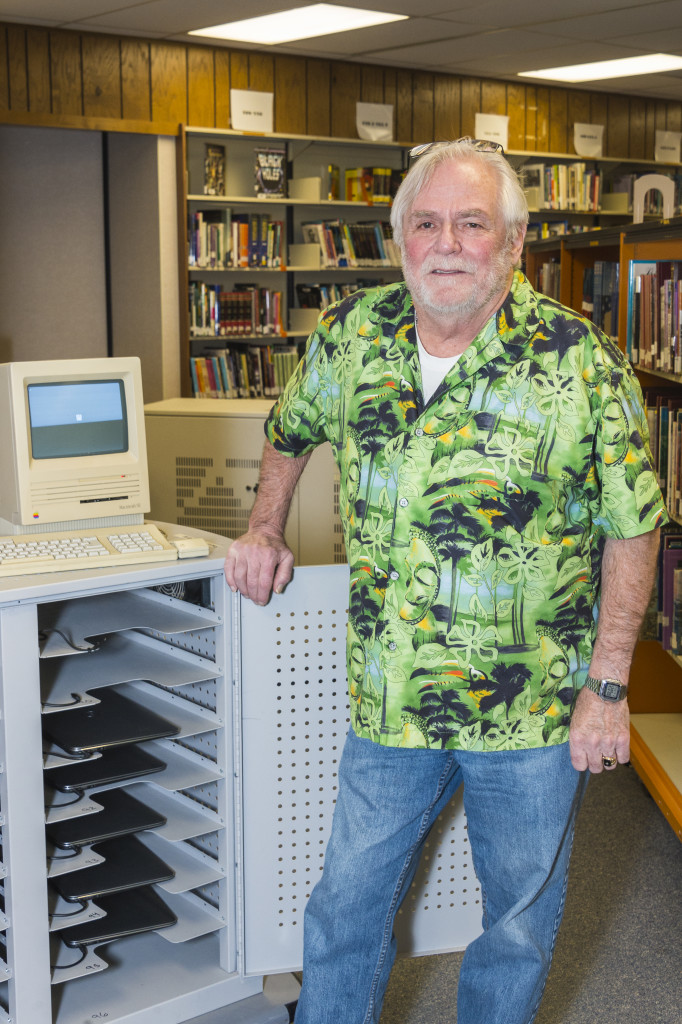

Greg Swain started a life in computers under Miriam’s guidance in the Gibraltar High School Library. Photo by Len Villano.

“I was shy, I didn’t go out for sports,” he said. “I was the geek. My introversion kept me into computers. Guys went out to party and I would hunker down in the glow of my computer monitor. If I ended up in a conversation with someone, I’d talk their ear off about computers or the program I was working on and they’d say something like, ‘Would you just shut up about this stupid program! It’s never going to do anything.’”

Gibraltar purchased a laptop computer in 1981, which meant Swain no longer had to write his code on paper. He graduated that year and moved on to UW-Green Bay, where he majored in computer science and found similar minds in his professors and fellow computer geeks who made toiling in the green glow of the screen if not cool, then at least normal.

By 1984 Swain created a groundbreaking DOS (Disk Operating System) program called Lodgical Solution that allowed lodging facilities to manage their reservations on a computer with a lightweight, graphical interface.

“Before that, we all had reservation books, and if you spilled your coffee on it you were in trouble,” recalled former innkeeper and Chamber of Commerce President Bob Hastings.

Swain developed Lodgical Solution with his parents’ resort, the Bluffside Motel in Sister Bay, in mind but it soon became a must-have for every resort, hotel and B&B in Door County. He said it wouldn’t have happened without the access to technology he received in high school.

“If it wasn’t for Miriam, I probably would be working as a paramedic or a nurse,” Swain said. “I would never have done what I did because I wouldn’t have had that exposure. You cannot overstate the role Miriam played in moving the internet forward in the schools. She was the one who kept plugging forward.”

Swain founded Bay Lakes Information Systems and soon his software was working wonders for innkeepers around the state, but there was a missing link. “These innkeepers in Door County would tell me that if they didn’t fill their rooms by a certain date, they were screwed,” Swain explained.

Visitors already on the peninsula often found vacancies by calling the visitor bureau or by calling resort after resort hunting for an open bed. Innkeepers didn’t have a way to let the bureau or their fellow lodging managers know that they had rooms available.

Swain’s solution was to create INNline in 1990, a program that connected all of the county’s Lodgical Solution users into a single database of availability. Innkeepers could now dial into a modem stored in Swain’s bedroom at his parents’ house and share their vacancies. When they dialed in with their information, the program pushed back every other users’ vacancy information.

At about the time Swain’s program was growing ubiquitous on the peninsula, a developer at the University of Minnesota named Mark McCahill coined the term “surfing the internet.” Erickson was hard at work making sure her students would know what the phrase meant. She fought for bigger technology budgets within the school and for grants from outside, including the groundbreaking Rural Datification Grants, designed to help small rural schools bring the internet to their students.

“Email was new to the scene and we needed access,” Erickson said. “And there was a big push for electronic classrooms, in which students could take classes remotely through television access that allowed them to interact with the teacher. This enabled a small school to offer advanced classes to talented students that it couldn’t afford to provide on its own. It was a forerunner of everything you can get online now.”

Gibraltar was deemed too small for the grant. Erickson was devastated but not deterred, and her quest to take the school to the technological forefront soon found another helpful torchbearer.

* * *

When John and Angie McMahon moved to Door County from Chicago with their two young sons in 1993, they expected to give up many of the conveniences and advantages of life in the city, but they weren’t willing to sacrifice their children’s education.

Before he started Door County Brewing Co., John McMahon was instrumental in bringing Internet to Gibraltar Schools. Photo by Len Villano.

McMahon was working for Cisco Systems, a giant technology provider for some of America’s largest companies. He was one of their early employees, selling the latest technology to workplaces racing to keep up with the new pace of business. They arrived in Door County just as Gibraltar lost out on the first round of Rural Datification Grants.

When McMahon caught wind of that, he saw an opportunity to make an immediate contribution to the school that would educate his sons.

“Just because we were moving to a small, rural community didn’t mean we didn’t want our children to have access to the technology of larger urban schools,” McMahon recalled.

Thanks to his experience, access and success at Cisco, he was in a position to donate the hardware – routers, terminals and servers – that the school needed.

“It was in part for the schools, but also to benefit our family and kids as much as anyone,” McMahon said. “When you move to a place like Door County, you expect to lose some of the luxuries of the city, but if you’re in a position that you can bring some of that technology here, you want to do it.”

With hardware accounted for, Erickson took a new approach, including all five of the county school districts in one grant proposal to bring WiscNet, the state’s nonprofit internet provider, to the peninsula’s schools. This time it worked, and Door County schools were soon among the best connected in the country.

“Miriam was aggressive,” McMahon remembered. “She was more instrumental than anyone in making it happen. She was a bulldog and that put Door County schools at the forefront of education technology.”

* * *

As Greg Swain was developing his skills and Miriam Erickson was fighting for technology funding, Rick Gordon and his wife Joan were feeling the pull to return home to Door County. Each had roots on the

Rick Gordon loved to tinker with computers, and by the mid-1990s, that became tinkering with new ways to bring the Internet to homes in Northern Door County. Photo by Len Villano.

peninsula that stretched back generations and after 20 years working with companies around the world in electronics, controls and computers, home was calling loudly to Rick.

By then computers were becoming a bigger part of commerce, even for small businesses in a remote tourist community like Door County, but few people on the peninsula knew much about maintaining them. Gibraltar High School was still teaching typing on actual typewriters (and would continue to do so until 1995), and Northern Door locals weren’t thrilled to drive 30 minutes to an hour to get their computer problems fixed.

“Locals kept telling me that we needed a computer store up here, so I opened Door County Computer in 1991 as a little project,” he said. He’d made enough money as a consultant over the years to free up time to invest in this side project, one that fascinated him to the point that he was soon spending 12 to 14 hours a day fixing, tinkering and learning about new computers while chipping at the edges of this burgeoning new thing called the internet.

“Working as a consultant was what I did for a living,” Gordon recalled. “But this was what was invigorating. To me it was all about starting this thing from scratch, from absolutely nothing, and seeing what I could do with it, where it was going to go.”

Gordon also began working for Gibraltar, Sevastopol and Southern Door Schools, helping to manage their networks and technology infrastructure. It was fortuitous timing. With Erickson and McMahon clearing the way to bring internet to the schools, Gordon would help install the infrastructure and get it up and running in 1993.

It was a huge step at the time, but would be the first of several larger steps in the year to come.

* * *

As Gordon worked on connecting the schools, Door County Chamber of Commerce President Bob Hastings was investigating what the internet could mean for tourism.

“By 1993 it was clear that the internet was going to be huge for tourism,” recalled Hastings, who has since retired to Florida.

Hastings saw potential for the internet to become a portal for visitors to get even more immediate access to vacancy information, improving their experience.

“At the time, we didn’t have cellphones,” Hastings recalled. “If you came up here without a room, you had to stop at a phone booth or go desk to desk. You could drive 100 miles through the county looking for a place to stay.”

In 1993, he asked the handful of people on the peninsula who understood the internet, including Swain and Gordon, to join him and secretary Karen Raymore for a meeting. He wanted to see if this group of local minds could get the internet beyond the schools and out to be used by the businesses of Door County.

“A lot of people left the table at that point,” Hastings said. “There wasn’t immediate money in it for them and they had other priorities, but Rick and Greg thought they could do it.”

Gordon and Swain didn’t know exactly how to pull it off, but they were excited by the challenge and soon they were spending hours around their dining room tables tossing ideas around. Eventually, someone had to stick their neck out and Gordon did, investing thousands in a 56K dial-up line that would allow multiple businesses and people to dial in for internet access. It was a risky investment for a business without a model, particularly one in a rural, disconnected area.

When he got it up and running in 1994 he called Swain. “I’ve got a dial-up you can log into! Try it out,” he said.

“That was amazing at the time,” Swain recalled. “That was the gateway to getting people connected.”

There still wasn’t a whole lot available on the early World Wide Web. It consisted of about 10,000 websites, all text-only without graphics or images. Nonetheless, Gordon had created a connection, and with banks of 32k dial-up speeds now available at the school, businesses and private residences could dial into the WiscNet connection as well.

For Hastings and the Chamber, this opened a world of possibility. They purchased and installed touch-screen kiosks throughout the county, where tourists searching for last-second rooms could search availability countywide simply and quickly. It was the first such system in the country.

“That’s everywhere now, but we were the first destination in the country to have that capability,” Hastings said.

In 1994 Gordon launched his own internet service provider, dubbed RickNet but officially known as Online Door County, venturing out on his own to sell dial-up access to homes in Northern Door. While cable companies and telecom industry paid scant attention to Northern Door County, Gordon built a network, eventually serving 4,000 customers via dial-up and later investing in new wireless broadband technology.

By 1995 the internet ballooned to 100,000 pages, and a year later it was 500,000. The ranks of those who doubted its influence were rapidly dwindling.

Northern Door County was online and it got there from the inside out, enabled by a fortunate intersection of federal funding, private enterprise, generosity and the needs of education, without help from the multi-national corporations that would come to dominate telecommunications but had scant interest in the small towns of Door Peninsula.

With local talent, resources, and a healthy dose of obsessiveness by Gordon, Swain and Erickson, Door County broke new ground in the tourism industry and laid the framework for a local technology infrastructure still thriving today.

Wireless Services Fill Connectivity Gap in Door County

In April of 2014, Rick and Joan Gordon sold their Internet Service Provider to a group led by Kevin Voss, Jim Matson and Gordon’s longtime employee Nate Bell.

Voss is one of many Door County residents who love the lifestyle and people of the peninsula, but can’t afford to be completely unplugged from their work. Before discovering wireless broadband service, Voss was on the verge of selling Door County property, frustrated by the lack of connectivity.

Charter cable internet service is only available along main corridors. That leaves the thousands of residents in rural parts of the peninsula in a lurch. Some residents turned to service through satellite providers, while others began using Cellcom’s wireless internet service.

Online Door County rolled out wireless broadband service in 2003, providing high-speed access through line-of-sight connections to towers throughout the peninsula.

When the business became available, Voss jumped at the opportunity to become an owner and expand the service.

“High-speed internet access is becoming more and more important every day, for business and tourism,” he said. “Our goal is to allow people to come up here and have the same level of service they can get back home.”

In the year since re-launching as Door County Broadband, the new owners have brought the installation price down to $99, with prices as low as $49 per month. They’ve also expanded their seasonal plans to make their services more attractive to the thousands of part-time residents who don’t need year-round service.

Bell was instrumental in the evolution of Online Door County from a dial-up system to a wireless broadband provider. He spearheaded NEWWIS expansion and infrastructure enhancements as its network administrator for 15 years, and is now the chief technology officer of Door County Broadband. Co-owner Matson is also the owner of Beacon Marine in Sister Bay.

The company now has 50 transmission sights throughout the county and is adding more, enabling them to fill gaps in service area with each new site.