Land & Water Conference: Groundwater Working Group Reveals Complexity of Problem

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

After thorough overviews of each water quality concern, attendees split into four groups and each tackled one issue. The goal was to break down the challenge of poor groundwater quality into two priority goals, including specific strategies to get there. Two hours later, conservationists from across the state could not come to a consensus.

Addressing nitrates and pathogens in the soil was the top priority. The first step in that goal is to bring every farm into the state under a nutrient management plan. Around 32 percent of operating farms in the state have nutrient management plans.

But most active debate centered on immediate assistance for well remediation versus continued data collection and research on possible solutions. Both ideas sought to gain political traction to get at long-term fixes.

“No matter what we do, if we’re successful at addressing the regional pathogen problem that’s a long-term goal,” said Kevin Masarik, groundwater education specialist with UW-Extension. “In the meantime, here are a lot of well owners who are aggrieved. Not including them in the top two priorities looks self-serving.”

Mark Borchardt, microbiologist with the United States Department of Agriculture, took the long view of the problem, recommending further research on best practices to prevent well contamination in the first place.

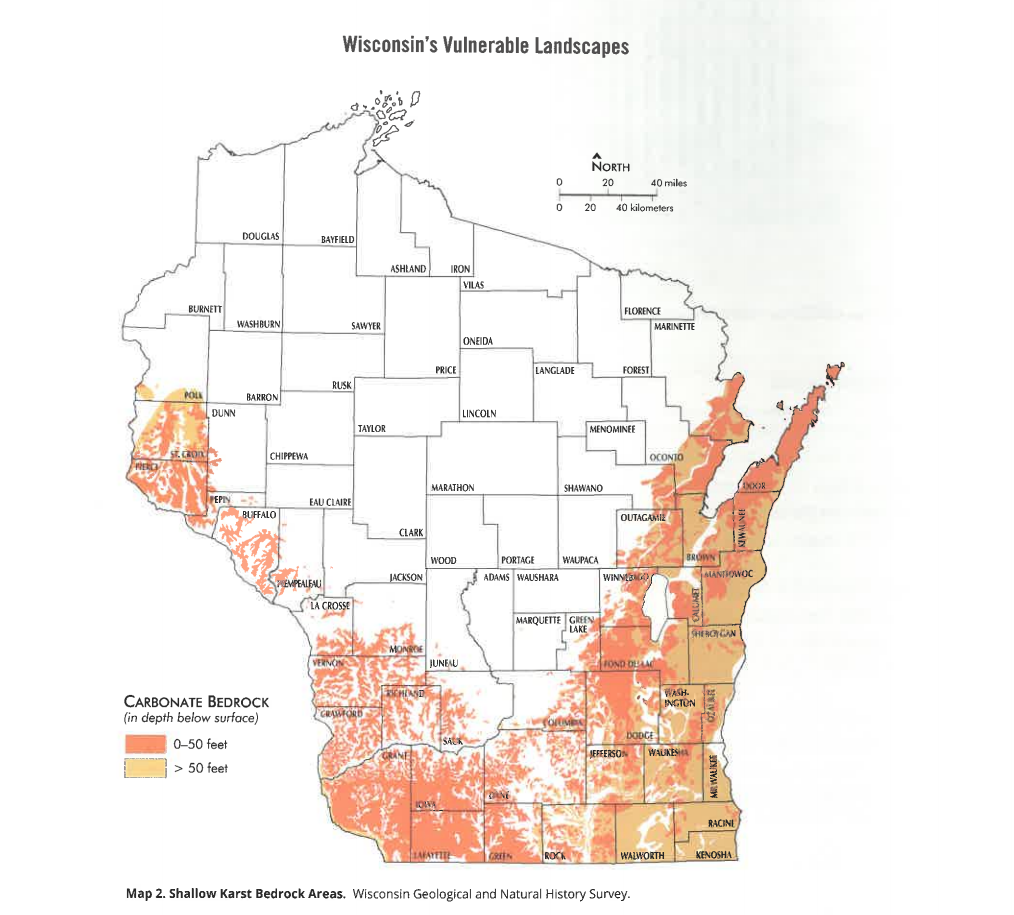

“What we need and what we’re working on with existing data are things like how manure applied is related to a well being contaminated,” said Borchardt. “We’re looking at setback distances, we’re looking at depth to bedrock, where’s that break point where you see lower contamination. We have the problem identified to get the political action.”

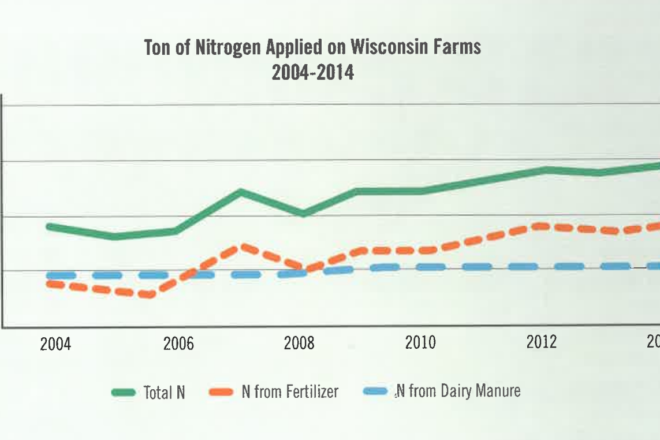

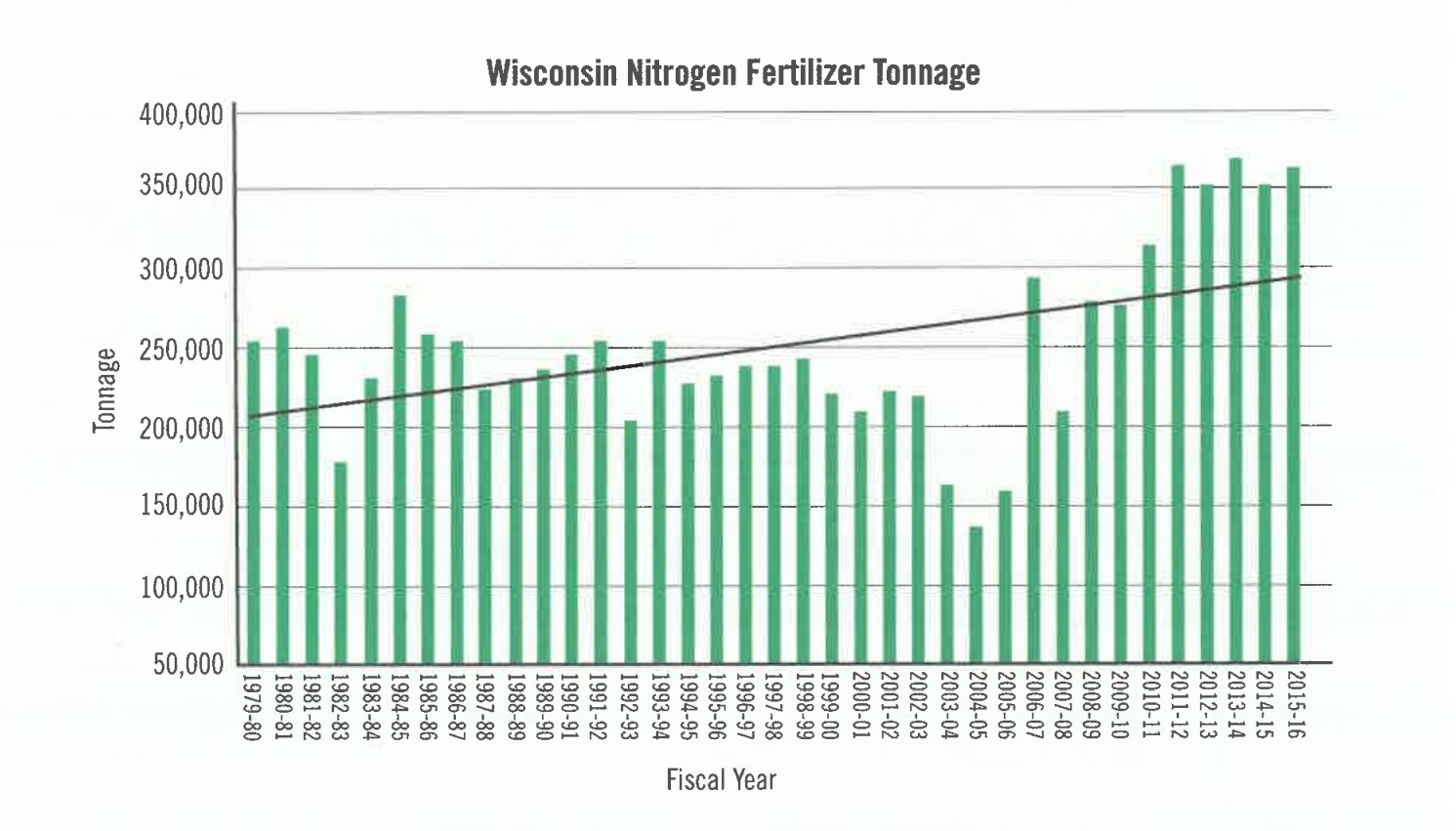

The amount of nitrogen fertilizer applied to Wisconsin farms has increased significantly since 2010 after holding relatively steady since the 1980s. Nitrogen is naturally converted to nitrate in soil which is then drawn up by plants to grow, but if plants don’t need more nitrate, it can leach into the groundwater supply. Image courtesy of the Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection (DATCP).

Masarik and others who agreed with him believed that immediate assistance for well remediation would get citizens more involved in the problem, achieving political will from the ground up.

“If everybody was willing to come together and make well compensation, if those avenues would open a little bit more, I think there would be less animosity and more understanding,” said Masarik. “I think most of them are tired of waiting for research. They just want clean water.”

However, there is a chance that a new well or well casing will not stop contamination. Kewaunee County board member Chuck Wagner said he drilled a new well at his own cost that ended up contaminated one year later anyway.

Peninsula Pride Farms has provided well remediation through cost sharing to six homes affected by contamination since they started the program last year.

The Department of Natural Resources (DNR) provides a well remediation program, but Russ Rasmussen of the DNR’s Division of Water said the program is rarely used.

“I think people are afraid we are going to swoop in with our black helicopters and make someone drill a new well, which isn’t true,” said Rasmussen. “You have to actually talk to the DNR to avail yourselves of that and there is mistrust of the DNR. We haven’t gotten many takers.”

Some argued that the DNR program was antiquated, citing one provision that only allows someone to apply to the program if their well has nitrate levels of more than 40 parts per million (ppm). The standard for acceptable nitrate levels in drinking water set by the Environmental Protection Agency is 10ppm.

But expansion of the program could be costly. Rasmussen estimated providing the program to all affected well owners would cost the DNR up to $200 million. The program is currently funded at around $180,000.

Borchardt also pitched what he viewed as the big ideas, such as creating a new agency of nearby counties in a single watershed.

“The state’s not working, the county is working so-so,” said Borchardt. “Develop some new organization that is regional in dealing with these issues.”

Davina Bonness, Kewaunee County conservationist, said the county departments lack regulatory authority to implement the needed change.

Borchardt pointed to other regional agencies such as wastewater districts as models for the organization, which would need to be granted some regulatory or taxation authority by the state.

The breakout meeting was noticeably void of many farmer or producer voices. Don Niles and John Pagel of Peninsula Pride Farms did not return to the conference for the second day due to other obligations.

“If there is a concern about political will then you need more allies,” said Rasmussen. “Identify those that would have political influence. For example, farm groups.”

No one from the Dairy Business Association, Wisconsin Farmer’s Union or Wisconsin Farm Bureau was in the breakout session on groundwater, although the groups did attend the conference.

Soil depths of below 50 feet are common throughout Door County but also in the southwestern part of the state. Image courtesy of the Wisconsin Geological and Natural History Survey.

Nancy Turyk, water resources scientist at UW-Stevens Point, suggested another big idea that many farmers would find hard to accept: an overhaul of farming systems in sensitive regions.

“We’ve been spinning for decades tweaking knobs with nitrogen and putting cover crops and it’s not getting better,” said Turyk. “The big picture is we need a paradigm shift and we need to talk about what is appropriate in these settings.”

Turyk suggested finding crops that don’t need significant nitrogen applications and planting those instead of traditional corn and potatoes.

This concept is already being hashed out in the rewrite of NR 151 regulating groundwater pollution in karst regions. It suggests that no manure can be spread on soil with less than two feet to bedrock. The change could functionally outlaw dairy operations in much of Door County, forcing those farmers to find other products that are more friendly to the sensitive environment.

In the final minutes of the marathon session, the group did consider the social impacts and hurdles of what they proposed – how do a bunch of scientists and conservationists convince laypeople that their data is sound and their methods both economically and socially beneficial?

“We’re getting a lot of the technical side,” said one member of the breakout group. “We need to build in that social aspect to create behavioral change and I don’t see a lot of that being discussed as a whole. We’re not talking about the social aspect of why someone makes a decision to do the things they need to do and how we encourage them to make that change.”

Read more about the topics discussed at the conference.

Surface Water Standards Set Low Bar