NR 151: A Rare Political Compromise

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

In today’s climate, we don’t hear about compromise, civil dialogue and quick political action very often. But groups from northeast Wisconsin rose above the fray to coalesce around a common goal: clean water.

Last week, the Natural Resources Board (NRB) unanimously approved the revisions to NR 151, rules governing manure spreading on agricultural land.

The new rules will impact all land on the particularly vulnerable karst topography and Door County will be most affected.

“There’s no disputing the fact that there are a very high number of contaminated wells in my area and I think there is also no disputing the fact that the current rules for manure application are not adequate to protect our water,” said Rep. Joel Kitchens. “The bottom line is that neither side is going to be completely happy with these rules but I think that shows they actually strike a very good balance.”

Of the approximately 25 people who spoke before the NRB, from farmers to conservationists and local residents, everyone supported the new rules. While there were a few who believed the rules did not go far enough, the general feeling was that they were heading in the right direction.

“I’d like to go on record of being strongly supportive of the revised changes,” said Don Niles, Kewaunee County farmer and founder of the farmer-led conservation group Peninsula Pride Farms. Niles said his group and other farmers are looking at additional ways to supplement the rule revisions, such as biodigesters, no-till fields and cover crops.

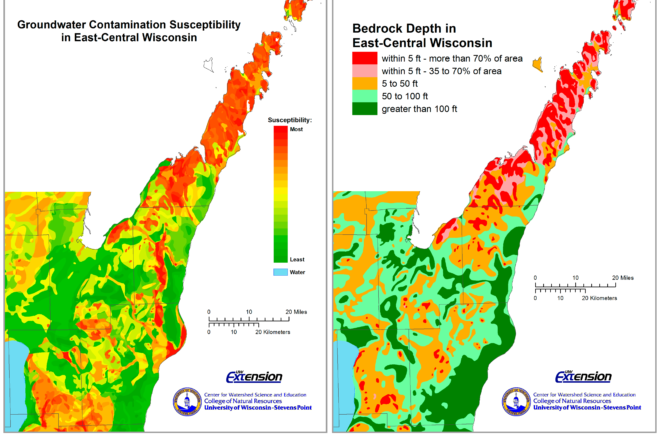

There are 1.6 million acres of cropland on Silurian bedrock. Of that, 17.6 percent, 283,795 acres, have less than 20 feet of soil on top of that bedrock and will be subject to restrictions under the new NR 151 rules.

“We request you adopt NR 151 as proposed,” said Paul Zimmerman, executive director of government relations for the Wisconsin Farm Bureau Federation. “We can’t stop with passage here today. We need to get it implemented, we need to monitor, and if things need to be adjusted we need to make changes as we learn things.”

This request to monitor and track progress was a common refrain from many who spoke before the NRB.

Mary Ann Lowndes, runoff management section chief with the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (DNR), said most of the work will fall to the county conservation departments, which have struggled with staffing and funding cuts in recent years.

“There are staffing issue in the counties in that their numbers have decreased,” Lowndes responded to a question from a board member. “The funding for grant programs has decreased as well. No, we don’t have adequate funding.”

If a farm is found to not be in compliance with standards, local conservationists cannot force a farm to implement new practices or equipment unless they can offer a 70-percent cost share.

Erin Hanson, department head for the Door County Soil and Water Conservation Department, said most of the cost share funds they get are from state grants.

“We’re committed to continuing the work with landowners as we do already,” said Hanson. “We actively pursue those cost share programs and will continue to do so. This was a good first step.”

In Kewaunee County, Davina Bonness is optimistic about their ability to enforce the new standards.

“I think Kewaunee County is a little ahead of the game,” said Bonness, Kewaunee County director of land and water conservation. “Our office has already been implementing these rules of NR 151.”

This map shows various soil depths on Silurian bedrock. Although shallow soil on Silurian bedrock is found in 15 counties throughout eastern Wisconsin, most is found in Door County.

Kewaunee County has 85 percent of cropland acres under a nutrient management plan (NMP), which will be the primary tool used to implement the new standards. If the new rules are approved, concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFO) will be held to them upon reissuance of their permits, which are renewed every five years.

Some board members were concerned that would mean some farms would not need to comply with the new standards for another five years, but NRB board member and dairy farmer William Bruins said farmers will likely cooperate in advance if they know what’s coming.

“Farmers in general have to operate with a lot of common sense,” Bruins said. “I think these rules changes allow farmers to do that.”

Despite unanimous passage by the NRB, there was rampant concern that the rules would be diluted when they got into the hands of the state legislature.

Kitchens, confident the Assembly would be supportive, was unsure about the Senate.

“I don’t know them as well,” Kitchens said about the Senate in an interview after the NRB meeting. “But I feel good about it. That will be my work.”

“A lot of citizens put a lot of faith in you,” Jennifer Giegerich, legislative director for the League of Conservation Voters, told the NRB. “It is really important that after you pass these rules today that you don’t just send them over to the legislature and let them do what they plan to do.”

“If these rules are to provide any relief, they can’t be further weakened,” said Sarah Geers, staff attorney for the Midwest Environmental Advocates. “These rules need to be approved without being weakened and implemented as soon as possible.”

The rule revisions will now go to the governor’s office and, if approved, will go on to the state legislature. If the legislature makes any changes, the rules will come back before the NRB. Lowndes expects the rule to be promulgated in the fall, after which DNR staff will return to the NRB with a plan to fully implement the changes.

What is Karst?

You can’t talk about groundwater issues in Door County without talking about our karst topography, the rock that all of our soil, trees, plants and grass sit atop.

Karst topography is a defining feature of the Door Peninsula landscape. In this area, the combination of shallow, gravelly soils above porous limestone means water moves very quickly through the landscape.

Karst is a landscape with surface and underground features like caves, sinkholes, disappearing streams and subsurface drainage. These features result when the bedrock (often limestone and dolomite) is easily dissolved by water. When the rock is dissolved, cracks and solution channels in the rock can form an underground drainage network. These cracks and channels can rapidly transport surface water and pollutants to groundwater.

In karst areas, groundwater can move as much as 100 feet or more per day, while in other areas, groundwater typically moves less than one foot per day. Eventually this groundwater resurfaces at a spring, wetland, river or lake.

Water quality is an important issue in a karst landscape. The fractured bedrock and the lack of much surface soil means that rainwater drains through much faster. In these areas, fertile soils can look parched between rainfall events, even if the amount of rainfall is adequate. Groundwater contamination from sources such as septic systems, agricultural wastes, and pesticides and herbicides is a higher risk in karst areas, because slow underground filtering is absent.

Where the groundwater in cracks and channels intersects with the surface (such as at the base of hills), clean or contaminated groundwater emerges into wetlands and streams. The water quality in these wetlands is a good indicator of water quality throughout the landscape, including the water we drink from local wells.

Source: My Healthy Wetlands: A Handbook for Wetland Owners, Eastern Wisconsin edition, a publication of Wisconsin Wetlands Association and the Aldo Leopold Foundation, 2014.