Organic Milk Production in Door County

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

There is a small handful of Door County dairy farmers currently producing certified organic milk. One of these is Gary Mosgaller – a third-generation farmer working the same land as his grandparents and parents before him – of Sunny Slope Farm in the Town of Jacksonport. With his herd of 55 to 60 dairy cows, he produces upwards of one million pounds (over 116,000 gallons) of USDA-certified organic milk per year.

Gary took over the family dairy farm operations in about 1980. At that time, and for another decade or so, he also raised canning and cash crops. While he never really liked all the chemical use associated with conventional farming, nor the noticeable impacts on his personal health, he says he didn’t really think seriously about farming another way until he “got sprayed all over by a custom sprayer in a field. I had them immediately stop – and we never did finish – the spraying. Then, the side of the field that didn’t get sprayed ended up growing better!” Shortly after that he began looking into and started the organic certification process, achieving his goal in 1995.

Gary explains that to become certified, “I needed to farm my fields without commercial [chemical] pesticides or herbicides for three years. After that, my animals needed to eat 80 percent organic-based crops for 10 months, and then 100 percent organic-based crops for the next two months [and forever after]. After the first 12 months of the animals’ organic diet, I was then allowed to ship my milk as organic.” He notes that when he began the certification process, “other farmers around laughed, really ridiculed us. Conventional farmers are trained to control everything – they do the harvesting, all the feeding, and the accompanying storage – they didn’t get what we were doing. After a couple of years, everyone started to figure out we weren’t going away. And, although I did take a hit in production levels during my initial learning curve, I was pretty quickly right back to where I was before. Plus, I don’t need to feed my animals out of stored feed during the summer – they pasture in and harvest the feed fields for me, which in turn saves me the fuel costs other farmers expend harvesting. Given current fuel prices, that will be a big savings this year alone.” Gary does note that with organic farming he has had “some weed issues, but you just need to take the time to learn about and correct those problems.”

In accordance with organic certification requirements, Gary’s animals have access to the outdoors a great deal of the time and are pastured for a certain percentage of their feed needs, the rest of those needs being met by things such as Icelandic kelp, which is high in minerals and amino acids. Gary indicates that these practices have led to a real improvement in the health of his animals, especially in their immune systems: “I don’t have to battle things you typically have to treat as a farmer. The health of my animals is so much better now and they live so much longer that I have the opportunity to sell animals, just keeping the best of the herd.” In addition to dietary requirements, certified organic producers are limited in veterinary treatment options for their animals if the animal is to stay in the production herd. “Mostly, I use herbal and garlic tinctures, aloe vera, and similar methods to treat the animals, and I’ve had very good success,” he says.

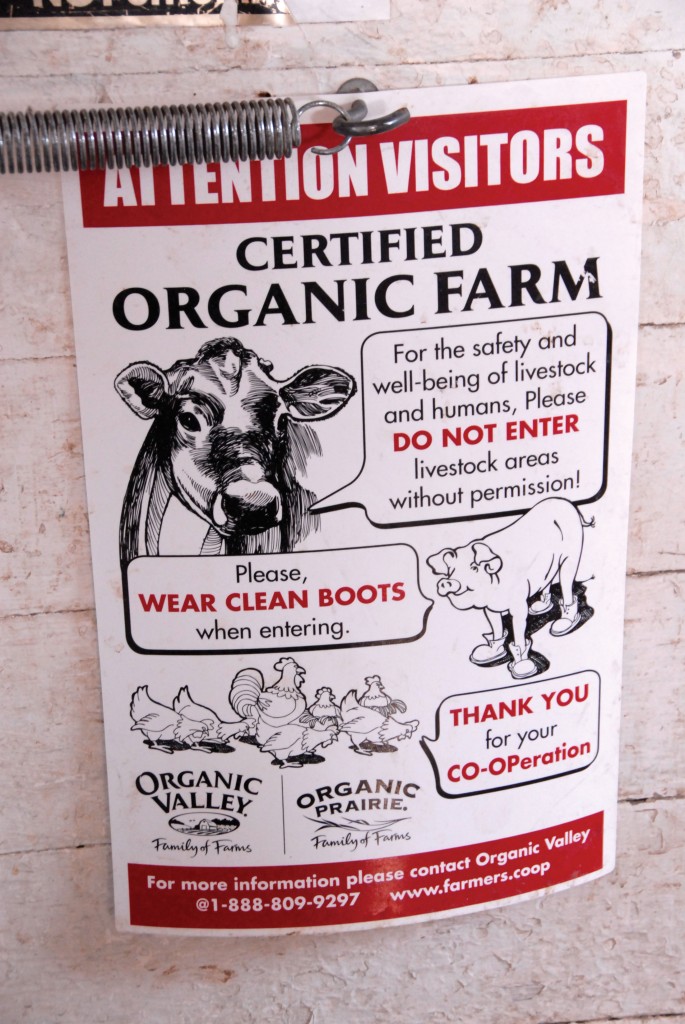

By now you’re probably wondering how you can buy some of Gary’s cows’ milk. Unfortunately, it is illegal in Wisconsin to sell milk directly off of a farm to a consumer. (Gary does know people in other areas of the state that have found clever ways around the law, but he’s not interested.) Gary instead contracts with Organic Valley, a company located in southeast Wisconsin, which purchases and processes all of his milk. He recalls that he was producer number 50 or so when he contracted with and started shipping his products to Organic Valley in 1995 or 1996; the company now contracts with over 1,000 producers.

Gary notes, “Organic Valley is a wonderful co-op – very farmer-friendly, farmer-concerned; they have an animals’ rights person as well as a vet and others on staff, and all are always willing to help when you have questions.” He also remarks that consumers would probably be interested that “Organic Valley has absolutely zero tolerance toward the use of hormones, antibiotics, etc. They are more stringent than the USDA requires them to be.” And, while it is extra work to be a certified organic producer, including annual inspections involving soil, blood, and seed samples, not to mention paperwork, Gary says it is worth it. He is paid a set price by Organic Valley which is high compared to a conventional producer’s return. That economic boost, coupled with the other savings realized by his organic milk production (such as lower feed, harvesting, storage, vet, and fuel costs), along with the human health and environmental benefits of organic farming, make Gary’s choice 15 years ago seem anything but laughable.

Why organic?

Organic farmers use no synthetic fertilizers, pesticides, genetically modified organisms, antibiotics, or hormones in raising and processing plants or animals. Producers cite many reasons for choosing organic farming methods, primarily related to health – theirs, as well as that of their animals, consumers, soils, water resources, and the broader ecosystems within which they live.

Consumers cite similar reasons for choosing organic products. Many are especially concerned about human health, questioning the impacts of conventional agriculture’s use of fertilizers, pesticides, antibiotics, hormones, and genetically modified organisms as well as housing and feeding practices for animals on large “factory farms.” For example, a total of 940 million pounds of more than 600 pesticides were used in the United States in the year 2000 in conventional agricultural practices. Conventional agriculture also uses large amounts of petroleum-based fertilizers, providing plants with nitrogen to fuel rapid growth but doing little to build up the soil and over time leading to suffocating algae blooms in local surface waters.

A number of organically-produced foods have recently been shown to have superior nutritional value. Milk from pasture-raised organic cows, for example, has been found to have significantly higher levels of vitamin E, Omega 3 essential fatty acids, beta carotene, and other antioxidants than milk from conventional cows raised in confinement.

Organic labeling and certification

The current United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) regulations regarding the labeling of foods produced using organic agriculture went into effect in 2002. Only food products that contain 95 to 100 percent certified organic ingredients may use the USDA Organic seal. The regulations:

- reflect National Organic Standards Board recommendations regarding which substances used in production and processing are allowed or prohibited;

- prohibit the use of irradiation, sewage sludge, or genetically modified organisms in organic production;

- prohibit antibiotic and synthetic hormone use in organic meat and poultry; and

- require 100 percent organic feed for organic livestock.

All agricultural products labeled “USDA Organic” have been verified by an accredited certification agency as meeting or exceeding USDA standards for organic production.

Resources and further information

The Organic Consumers’ Association website – http://www.organicconsumers.org/ – has a wide array of information, news stories, and on-line discussions and debates regarding organic foods.

The Organic Valley website, http://www.organicvalley.coop/, contains information about their company, products, and philosophy as well as other links to information about organic agriculture and foods. Gary raves about Organic Valley’s products, particularly their raw milk cheddar. He proudly notes that the company’s producers in the eastern portion of Wisconsin (like himself) typically find their milk going toward the company’s cheese production (western producers’ product is typically for milk, and southern, butter).