The Origins of Labor Day: They Labored So We Don’t Have To

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

Labor Day is known as the three-day weekend that marks the end of summer. People often mix it up with Memorial Day, simply knowing both are long weekends that serve as bookends to the summer. But a day off work is rarely linked with a holiday to celebrate working in the first place. Labor Day is a celebration of the labor force and a grateful nod to the people who made our work lives what they are today.

Through the late 1800s, as industrialization began taking the place of agriculture as the nation’s future industry, working conditions were the sacrifice of increased production. Bigger machines and more workers began to fill factories whose walls were not growing any wider.

Workers, including children, often toiled through 12-hour days and seven-day weeks for just a dollar or two a day. The working conditions were even more appalling than the hours.

“Puddlers, the skilled workers who tended the blast furnaces, routinely endured temperatures exceeding 160 degrees,” wrote John Gurda of workers at the Milwaukee Iron Company in 1881. “The workers had few defenses. There were no electric fans, because there was no electricity. The furnace crews generally worked bare-chested with Turkish towels wrapped around their necks to soak up some of the sweat and leather straps over their hob-nailed boots to prevent burns from spilled iron. Every worker downed two to three buckets of ‘oatmeal water’ during his shift, usually laced with lemon juice.”

A Milwaukee Sentinel reporter on site wrote, “none but the men who have worked in these great hives of human industry, among immense furnaces and molten and seething metal, have any conception of the heat which a mill-hand has to endure while at his hard and tedious labor.”

Similar conditions were found in all industries from mining and logging to construction. Safety technology offered little respite and after a while, the workers had enough. But instead of asking for better conditions or higher pay, all they wanted was a shorter workday.

The push for an eight-hour workday began with the Industrial Revolution and the adopted slogan, “Eight hours labor, eight hours recreation, eight hours rest.” But advocates quickly realized that cutting back from 12 hours to eight hours was a lofty dream.

In 1835, 20,000 carpenters, miners, bricklayers, painters and other professionals in Philadelphia called for a 10-hour workday. Their wishes were granted along with increased wages. Recognizing that this success would likely trickle into a labor movement across the country, the federal government quickly got on board by passing an eight-hour law for federal employees in 1868.

Meanwhile, Milwaukee, with its industrial economy, became a stronghold for a chapter of the Eight-Hour League. Labor successes in the Brew City were quickly followed with tragedy.

This public domain image of the May 4, 1886, Haymarket riot in Chicago was originally published in Harper’s Weekly.

On May 4, 1886, workers held a protest rally in Chicago’s Haymarket Square. When police arrived at the rally to disperse the crowd someone threw a bomb, killing seven police officers and at least four civilians.

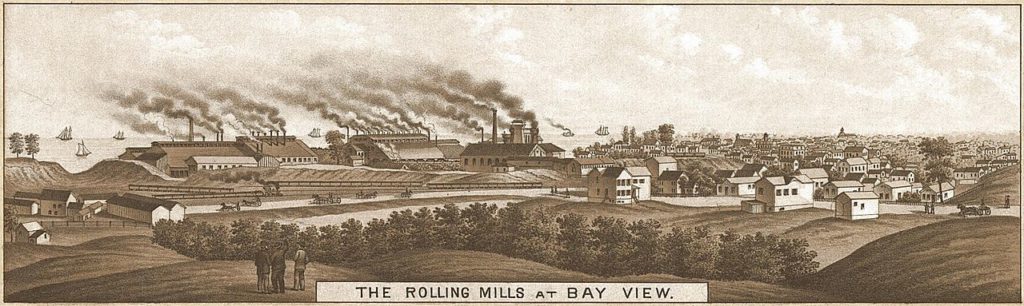

The Bay View tragedy in Milwaukee – the state’s most violent labor conflict – came just a day after the Haymarket Affair. At least 1,500 workers marched on the Bay View Rolling Mills after shutting down nearly every other business in the suburban neighborhood. Governor Jeremiah M. Rusk ordered 250 state militia to stand in their way. They were told, “Pick out your man, and kill him.”

Seven died in the conflict and the eight-hour movement died with them, for the time being. Instead of marching, labor advocates took to politics with congressmen and state legislators from the People’s Party elected into office that fall.

The Bay View rolling mills, where a labor march that left seven dead ended. Public domain.

The proximity of the Bay View Tragedy and the Haymarket Affair gave a harsh new weight to the labor movement.

Labor laws as we know them today didn’t come around until the Fair Labor Standards Act in 1938, part of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal. Before the success of organized laborers seeking better working conditions, governments agreed to give the laborer just one extra day off.

The first Monday of September became a national holiday by act of Congress on June 28, 1894. Although many local governments were already giving their municipal employees a day off to celebrate the American worker, the act of Congress was more of a bargain than a blessing.

When a strike of the American Railway Union (ARU) threatened to leave postal railways unfinished, President Grover Cleveland ordered 12,000 troops to crush the disobedience. While the ARU dissolved after the conflict, many believe Cleveland granted the national holiday as an apology for the 30 people killed during the strike.

It is hard to think that such terrific violence between industry workers and government could give rise to an enjoyable weekend of picnics, boating, fireworks and music.

In Wisconsin, the battles continue. In 2011, as many as 100,000 protesters marched on Madison’s capital to fight against Governor Scott Walker’s bill that prevented unions in the public sector to bargain collectively. Although challenged in court, it looks like that part of the Wisconsin Budget Repair Bill is here to stay.

While enjoying your long weekend free from laboring, remember those who endured brutal conditions, fought, marched and died so you could work in an office with air conditioning, bathrooms and a clock indicating when to leave after eight hours.

Sources: John Gurda’s Cream City Chronicles, Stories of Milwaukee’s past; Wisconsin’s Labor History Society; Philip S. Foner’s History of the Labor Movement in the United States