Perspective: ‘Southern Change Gonna Come at Last’?

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

Back around the turn of the century I was talking to an eccentric Texas musician during a break in one of his first Wisconsin shows, when he informed me that a lot of his Texas buddies didn’t want to play for us Yankees, but he thought we were all right and didn’t mind playing for us. And then he delivered the biggest non sequitur I’ve ever heard: “My great-granddaddy killed his first Yankee when he was 16.”

Which prompted me to remind him that the Civil War is long behind us, but also made me realize that we still are a country divided by our very different histories.

Even though this was a goofy musician talking, I figured he didn’t live in a vacuum down there in the heart of Texas and was just speaking the truth of his reality, and that the Civil War obviously remains an unresolved issue for some.

And then I forgot about that encounter. The South and its festering problems did not enter my sphere of consciousness again for many years.

Fast forward to the week after Donald Trump was elected president of this country. I drove to Memphis for a week of vacation.

I knew no one there. I knew little about the city other than its musical history – Hi Records, Sun Studios, Beale Street, Graceland, Elvis, B.B. King. And, of course, I knew it was the city where Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated in 1968.

I wanted to be surprised by Memphis, and it did not disappoint.

The racial divide is apparent. Blacks live here. Whites live there.

I did a lot of walking in Memphis, and during one of those walks came upon a park surrounded by hospitals, hence the bizarre name – Health Sciences Park.

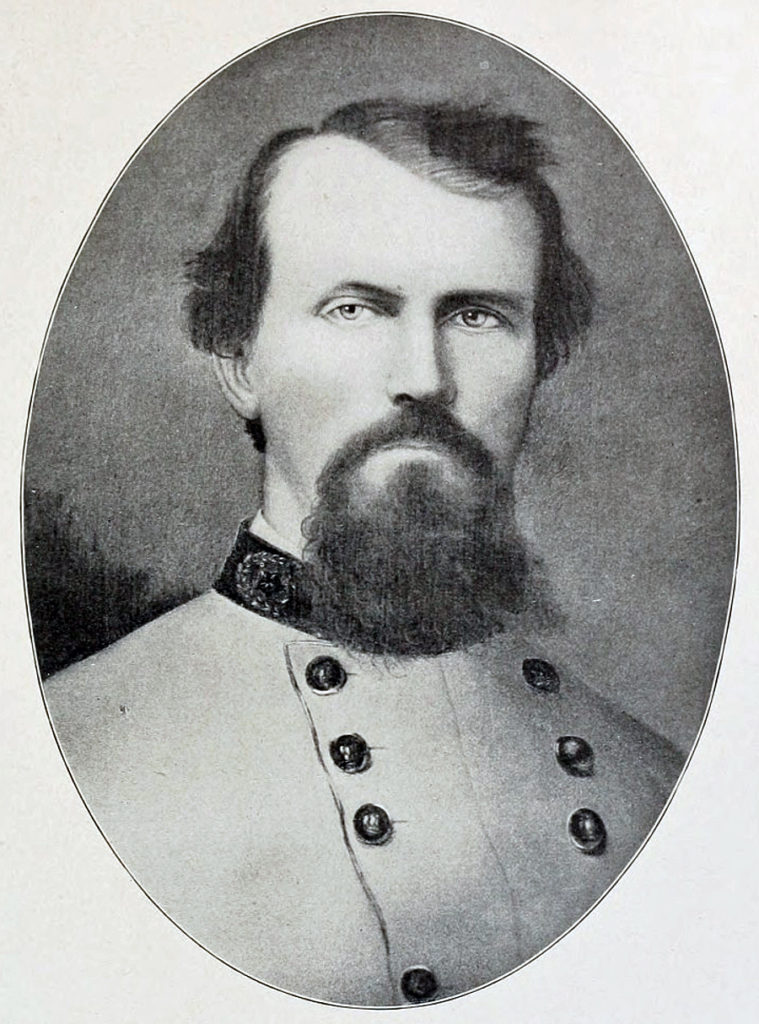

At the park’s center I was surprised to come upon a giant brass statue of a uniformed horse rider. It turned out to be Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest. I had heard the name, but was not familiar with the life of the southern Civil War hero, something I quickly corrected by visiting a local bookstore.

Forrest was a self-made man who became wealthy through real estate and then as a large-scale slave trader. He was the only man – north or south – to enlist as a private and rise to the rank of general. Unlike his military colleagues, Forrest did not go to West Point, and may not even have been literate. However, he was greatly feared by Union officers for his tactical skills and his motto, “war means fighting and fighting means killing.”

In April 1864, Forrest’s troops captured Fort Pillow, about 40 miles north of Memphis. Close to 300 Union soldiers, most of them black, were massacred, while only 14 Confederate soldiers died in the actual battle. There was a Congressional inquiry, but nothing came of it. Forrest and his men denied there was a massacre, saying inept leadership and the blacks’ refusal to surrender is what led to their deaths.

After the war Forrest was enlisted to join a new group called the Ku Klux Klan. His ruthless leadership skills were sought by the organizers, and he became the KKK’s first Grand Wizard. But he soon parted ways with the organization, reportedly over violence against blacks, and attempted to abolish the organization before leaving it.

In July 1875, he gave a speech to a black organization in Memphis in which he spoke of reconciliation.

“We were born on the same soil, breathe the same air, and live in the same land. Why, then, can we not live as brothers?” Forrest asked.

That speech – in which he said it is his motto to elevate every man, and that he would use his influence to strengthen “fraternal relations” between the races and elevate blacks “to take positions in law offices, in stores, on farms, and wherever you are capable of going.” – sounds, in the context of the times and where Forrest was just a decade before, like a very powerful and conciliatory speech. Forrest was roundly denounced as a race traitor. Two years after that speech he died from complications of diabetes, at the age of 56, and was buried in a traditional Memphis cemetery.

In 1900 the newly created Memphis Park Commission named its first greenspace, an eight-acre square, Forrest Park in honor of the general. Soon after, someone had the bright idea of exhuming Gen. Forrest and his wife, Mary, from their resting spots and move them to Forrest Park. Sculptor Charles Niehaus was commissioned to create the statue that has stood since 1904 above the couple.

On the day of my visit, a small sign was planted in front of the statue, making everyone aware that it is a felony in the state of Tennessee to deface or destroy a monument marking a grave.

In 2015, the Memphis City Council voted to change the name of Forrest Park to Health Sciences Park, but attempts to remove the statue and the remains of the Forrests have, so far, failed.

In the wake of the Charlottesville incidents, the Forrest memorial is back on the minds of Memphians. Someone placed a white hood on the statue last week and some have threatened to pull it down, while Memphis Mayor Jim Strickland announced the city is preparing to sue Tennessee in order to remove the state-protected statue of Forrest and another of Confederate President Jefferson Davis that stands in a park along the Mississippi River in downtown Memphis.

It seems like the time for celebrating the heritage and history of secessionist terrorists in public spaces is over. Stick the statues in museums so we don’t forget, but don’t allow them to remain such a blatant reminder of the spirit that drove a stake through the heart of this country less than 100 years after it was formed on the principle of freedom for all.