The Harvest of 1945: German POW Camps Filled Door County’s Labor Shortage

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

Anyone who has visited the Door County Maritime Museum in Sturgeon Bay or seen Jacinda Duffin’s play Loose Lips Sink Ships knows that local shipyards were frantically busy during World War II, employing people from all over. How many Door County residents and visitors are aware, though, that during 1945 and 1946 German prisoners of war were employed here?

Beginning in November 1942, many World War II prisoners of war (POWs) were housed in the United States. In addition to its own prisoners, the military agreed to take custody of all prisoners captured by Great Britain after that date, and quickly realized it was easier to house, feed, and guard them in the U.S. at military and other existing institutions rather than abroad. Furthermore, the 1929 Geneva Convention relating to the treatment of POWs allowed under certain circumstances their use as labor, and the U.S. was facing severe labor shortages.

The abandoned Civilian Conservation Corps site in Monroe County, Wisconsin was designated in 1942 as one of the first of ultimately 156 POW base camps in the country. Eventually, POWs in Wisconsin were housed on two base camps and in 38 branch camps, with the state having by 1945 about 20,000 of the more than 420,000 POWs in the U.S. Most of Wisconsin’s POWs- like those in other states – remained until June of 1946.

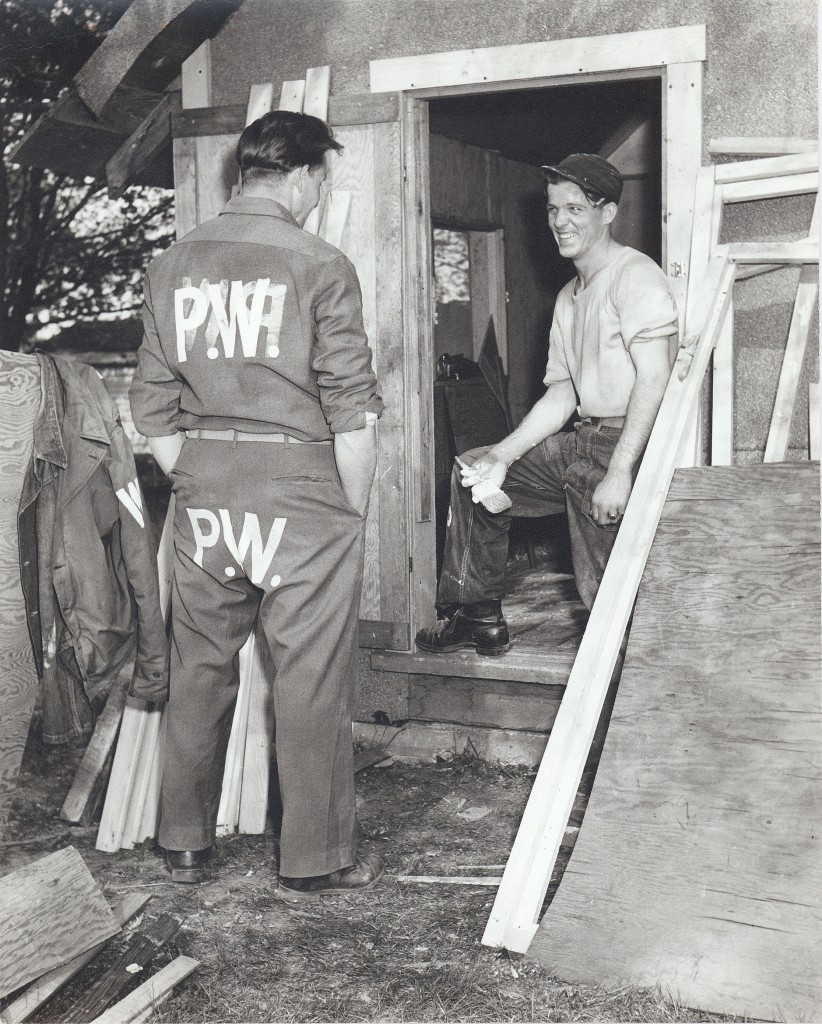

Once military base camp labor needs were met, POWs were placed in other areas to be employed by private business owners. In Wisconsin, POWs worked primarily in seasonal agricultural employment, although some worked in the lumber industry or manufacturing. Because of the Geneva Convention stipulation that POWs be paid for their work, those working in the U.S. received 80 cents per day in “camp scrip” plus a 10-cent gratuity for personal needs. (POWs were paid in “camp scrip” so they could make purchases only at the military bases or camps – the money was worthless elsewhere if a POW escaped. Prisoners were allowed, however, to start savings accounts redeemable upon repatriation.) So as not to undercut union and other wages, the federal government collected the difference between the pay the POWs were allowed to keep and wages paid regular employees. POWs working in Wisconsin therefore realized an estimated $3.3 million for the U.S.

Early in 1945, the government decided to establish Camp Sturgeon Bay as a temporary branch camp. The POWs were from Field Marshall Rommel’s Afrika Korps and were coming primarily to assist cherry orchard owners. Lack of labor during the war – despite the 1944 picking season importation of roughly 2,000 Jamaican, Barbadian, and Mexican workers – meant that local orchards had been forced to leave literally millions of pounds of cherries on trees in previous harvest seasons. Local canneries were also losing significant product – nearly 30 percent in 1944 alone – due to labor shortages.

The first 81 POWs placed at Camp Sturgeon Bay arrived in mid-May – nearly a month after originally promised – to hostility from some residents. Local families had lost approximately 50 people to the war in Europe, misinformation regarding POW pay had been printed (although quickly corrected in a subsequent story) by the Door County Advocate, information regarding Nazi concentration camps had surfaced, and accounts of mistreatment of U.S. soldiers in European POW camps abounded, all compounding local resistance. Some also believed POWs would be taking jobs away from local residents, incorrectly assuming cutbacks in defense work were imminent and not realizing local orchard owners were desperate for help.

This initial hostility lessened considerably after accurate information about the POW pay system was circulated, the press was offered tours of the camp, and an informal educational campaign was undertaken by the military emphasizing the positive economic impact the POW workers would have locally and nationally. The first POW arrivals to Camp Sturgeon Bay were quickly put to work cleaning up and cultivating orchards, although some also worked in potato fields. Another 500 arrived from the Nebraska sugar beet fields in early July, and by early August, all expected had arrived. Camp Sturgeon Bay contained 2,140 POWs, all of German ancestry.

Prisoners were housed throughout the county, including Fish Creek and Ellison Bay, where their labor filled a desperate worker shortage.

Although established and used only temporarily, Camp Sturgeon Bay’s peak population was second only to Billy Mitchell Field. Unlike the other branch camps in Wisconsin, it was actually comprised of seven scattered camps. These groups of POWs worked in the summer of 1945 to pick cherries alongside local residents and the more than 1,100 foreign workers again imported. The largest group of POWS – around 500 – stayed at the fairgrounds in Sturgeon Bay. The others lived and worked at six of the larger local orchards, housed in existing barracks for migrant workers: 350 at Martin Orchards, 250 at Reynolds Brothers, 300 at M. W. Miller’s, 200 at Goldman’s near Little Harbor, 250 in Camp Witte at Fish Creek, and 290 at Friedlund Orchard in Ellison Bay.

Smaller orchards could also use POWs as labor after larger orchards had enough workers, picking up the POWs from the camps and returning them at night. While the larger orchards had armed guards, these smaller orchards did not. Still, none of the orchards ever reported any major problems, although false rumors of an incident where a prisoner shot a guard circulated wildly. In reality, the POWs were so well behaved, the guards – and the lax attention they paid to their guns, hanging them in cherry trees or even handing them to POWs to hold – were considered by all to be a joke even at the larger orchards.

After the 1945 cherry harvest, most of the POWs were sent to Michigan and Illinois for other harvests. About 100 remained in Door County into 1946, helping with apple, potato, and sugar beet harvests and working to process fruit in local canning factories such as Door County Canning Company, Thomas H. Smith and Son, Jennings Packing Company, and Reynolds Brothers Canning Company.

All in all, German prisoners of war picked 508,020 pails of cherries – an average of roughly 20 pails per man per day- in Door County during the summer of 1945, earning $101,604 for the U.S. government and, by many accounts, saving the area’s cherry crop that year.

Despite the initial hostility the Camp Sturgeon Bay POWs faced from some Door County residents, most recollections of interactions with the Germans tell of pleasant, amiable exchanges, with many remembering kindnesses extended in both directions. There are even a few funny stories, such as the two POWs, who, when they found out they were soon going home to Germany, jumped over the Friedlund Orchard camp fence and headed to Lake Michigan. They had “decided they couldn’t leave without a swim in this great lake…The duo found the lake to be ‘much cooler and much rockier than [they) ever expected'” (Cowley, p. 247).

By the 1940s, approximately one-third of Wisconsin’s population had German ancestry. Many were first- or second-generation immigrants with family fighting on both sides of the war. Some German POW prisoners sent to the state were actually related to Wisconsin residents. Wisconsin POW camps received visitors from all over the country who came to see relatives or in search of information regarding family members in Europe.

Resources and Further Information

Resources and Further Information

Community of Friends: Door County Wisconsin During World War II, UW-Milwaukee Master of Arts Thesis in History, Laura Toft Graan, 1999. View or purchase a photocopy at the Wisconsin Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA) office: Wisconsin OVA Museum and Foundation, 30 West Mifflin Street, Suite 300, Madison, WI, 53703. (608) 267-1 790. www.museum.dva.state.wi.us. Toft Graan’s sources for the section on German POWs were Door County Advocate articles and interviews she conducted.

Stalag Wisconsin: Inside WWII Prisoner-of-War Camps, Betty Cowley. Badger Books, Inc.: 2002. Cowley’s sources for the chapter on Door County were Door County Advocate and Green Bay Press-Gazette articles and interviews she conducted.

Photography by W.C. Schroeder.