50 Years of Icelandic Horses

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

Two Icelandic immigrations came to Washington Island, one human and one animal.

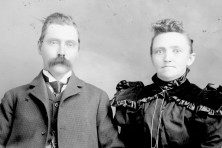

The most celebrated immigration began in 1870 when four young Icelandic men found work on Washington Island. They encouraged countrymen to follow, soon making this an Icelandic settlement.

Nearly 50 years ago, in 1964, a group of friends gathered at the home of the late Arni and Mary Richter. Their conversation about the island’s heritage led to the consideration of Icelandic horses as a way to boost the island’s tourism image.

Arni Richter, Washington Island Ferry Line owner and grandson of Icelandic immigrant Arni Gudmundsen, wrote to Samuel Ashelman, Jr., of Ashton, Maryland. Ashelman’s Icelandics were imported in 1960, the first such horses brought to North America from Iceland. He had “about 45” in his herd by then and said he would be willing to sell a few mares and foals.

Richter’s January 14, 1965 letter stated: “A small group on the Island became interested in these ponies last year…We are thinking seriously of purchasing 10 ponies and building a small herd. Washington Island is becoming a very popular tourist center and we feel there would be a good demand for this service…it would be most fitting and interesting to have these ponies.”

In September 1965, eight bred mares (including seven of the original importation) plus seven foals were trucked from Maryland at a cost of $400. Initial island owners were the Richters, Hansens, Kleinhans, Rutledges, Kohlers, Lehmans and Jack Myers, each paying $300 to 400 per horse.

Elding and Hrefna, a chestnut and a black, respectively, were the Richter horses, each having Icelandic names, a tradition that would continue as new offspring were born. In a marketing coincidence, a National Geographic photographer in late 1965 posed their daughter Adele Richter with the horses to help demonstrate the island’s Icelandic ties in a spread about Door County.

Washington Island’s Icelandic horse numbers fluctuated, but most of today’s horses are descended from those shipped in 1965.

Laurie Veness of Field Wood Farm has 14 Icelandics, down from more than 40 horses she owned years ago. She’s proud to say that her horses represent the oldest, continuous Icelandic horse herd in North America. Extremely knowledgeable about Icelandics and horses in general, having earned her horse science associate degree at State University of New York, Veness prefers Icelandics over other horses. She began building her herd from two mares in 1971, breeding them, offering trail rides and lessons, and gradually learning more about the Icelandic horse.

Veness is a proponent of the unique characteristics found in Icelandic horses, one of five basic horse lines that evolved into today’s horse breeds. Historically, Icelandic horses were isolated and protected, which preserved their bloodline for more than 1,000 years. To this day, Iceland allows no other horse lines to be imported.

Icelandic horses are sturdy and sure-footed, well suited to the rocky terrain and lava fields found in Iceland. They’re strong, capable of carrying loads one-and-a-half times more than most horses of similar size. Thick, triple-layer winter coats help them endure rain, sleet and snow, conditions often found in Iceland, and as a result they do best outdoors with m inimal shelter and not shut up in barns, Veness says.

inimal shelter and not shut up in barns, Veness says.

Icelandic horses are typically long-lived, maturing slowly. They reach physical maturity at about 10 years, bear young well into their 20s, and can often be ridden – and not just put to pasture – into their 30s. Curious, friendly and dependable companions, Icelandic horses can be ideal for younger riders.

Veness emphasizes that Icelandics are horses – and not ponies – due to their ancestry, even though they may be of shorter stature than many other horse types. The term pony, she explains, is based upon an arbitrary height measurement.

“Do you remember this one?” Laurie asked as we approached a pen. “Your daughter, Evy, rode Star in the county fair.”

Star (Stjarna in Icelandic) is now 38. She came from Elding, of one of the Richters’ first horses. Several of Star’s offspring were pastured nearby. Laurie whistled and two gelding brothers instantly responded, running briskly toward a pen to mingle and feed alongside several other horses. Coat colors vary with Icelandics, ranging from deep black to golden to pure white.

“Winter coats started a month ago,” Veness noted. “Thick hairs grow in, some that can reach up to eight inches in length.”

Veness said she came to appreciate the Icelandics more when she had been away from them for a time. A commonly held view was that to be a good horse, that horse must be tall. But with the Icelandics, she says, that’s not true.

“My perspective changed. I learned there was something about their gait that was different,” she said. “It wasn’t long before I was won over by them.”

They have an unusual fourth gait called “tölt,” natural to all Icelandic horses. Veness described the tölt as a “four-beat running walk,” resulting in a rider having almost no up or down motion; an effortless, smooth gait that makes Icelandic horses highly sought after by riders.

Years ago, one of Veness’s Field Wood Farm students was Evelyn Purinton, now 38, granddaughter of the Richters. She fell in love with horses at an early age and in time owned Bylur (pronou nced “bay-lure”). Just out of high school, Evy authored the children’s book, Bylur, the Icelandic Horse, in which she described her daily island activities with her horse when growing up. For a number of summers, Bylur was a top-seller among children’s books in Door County.

nced “bay-lure”). Just out of high school, Evy authored the children’s book, Bylur, the Icelandic Horse, in which she described her daily island activities with her horse when growing up. For a number of summers, Bylur was a top-seller among children’s books in Door County.

Evy (now Evy Beneda) teaches sons Zander and Atlas about horses, and gives beginner lessons to young riders in a pony ring. Recently, she jumped at the opportunity to add the Icelandic Blitzen to her stable of non-Icelandic horses. Icelandics remain at the top of her wish list, even after riding and appreciating many breeds and horses of varying sizes since her teenage years.

At Norse Horse Park, just off Washington Island’s Main Road, Jerry and Mary Ann Maiers keep a pair of Icelandic horses along with several other Scandinavian horses. Their Icelandics are from an Iowa farm, and they pasture now with other northern breed horses including a Fjord and a Gottland, horses somewhat larger than the Icelandics.

The Maiers believe early horses from Norway and Sweden were forerunners of today’s Icelandic horse bloodline. Although their farm was closed to the public this past summer, their goal is to help educate the public. The Maiers don’t breed their horses or offer riding.

Far away, Iceland continues to impact Washington Island to this day, with lasting contributions from its Icelandic immigrant citizen descendents helping shape the community. Similarly, since its arrival here 50 years ago, the Icelandic horse continues to bolster island cultural contributions.