The Story of the Pulse

by Jim Lundstrom

How many people can say their job is to create something out of nothing? Who would even want that job, because what if your creation was something that no one wanted?

But creating something out of nothing is the very essence of a newspaper. Each day or week — depending on the publication schedule — begins with a bunch of blank pages that have to be filled with engaging, original content and information, as well as the advertising to pay for it all.

What kind of nut would take the gamble to start a newspaper, especially after the birth of the internet?

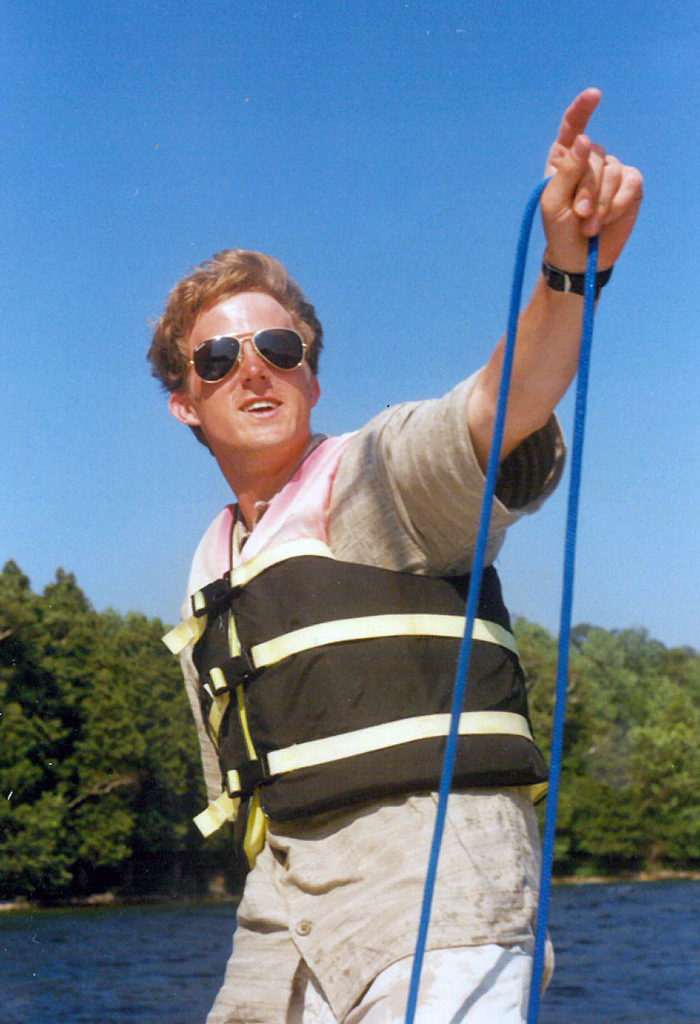

Meet David Eliot and Thomas McKenzie, who in the summer of 1996 became co-founders of the Peninsula Pulse. McKenzie, from Appleton, Wisconsin, and Eliot, from Ipswich, Massachusetts, met while they were English majors earning liberal arts degrees from Lawrence University in Appleton. They would spend their summers working in Door County, but McKenzie’s roots here went even deeper. His uncle James McKenzie was a producer at Peninsula Players Theatre from 1960 until his death in 2001.

Tom Mackenzie believed Door County would be a good place to start an arts and entertainment publication. Submitted photo.

“I was a kid who would run around the theater, meet everybody, go backstage. I really got to know the people who came every summer,” McKenzie said. “It was captivating. I was an ingénue there for some time and played many, many roles. It was always a place that inspired me and had a kind of magic and intrigue, everyone working together on a common, imagined vision, sitting on a back bench with my uncle watching the opening night show, watching it from his perspective, to see this endeavor come together. I would volunteer to usher and you really start to talk to people, welcome them to the place, set the tone for the evening of joyous and spellbinding theater under the stars with bats flying around the house.”

Because of that, Door County was a second home to McKenzie.

“I knew it as a place where creative projects could happen and there were really interesting people to engage, and you had a really positive and supportive community for creative ventures. I learned all that, I think, through my time at Peninsula Players,” he said.

Dave with his St. Bernard Charley. Dave’s interest in digital technology resulted in the birth of the Peninsula Pulse. Submitted photo.

Back in high school in Massachusetts, Eliot was introduced to desktop publishing.

“My senior year in high school [1989], there was PageMaker,” he said, referring to one of the earliest desktop publishing programs. “My English teacher was talking about how we could sit in front of a computer and make a newspaper. Layout and design was just shifting from cut and paste to submitting something entirely digital. I was assistant editor and took over a computer and started making a newspaper.”

Eliot said it was the people involved that made producing the school newspaper interesting.

“I think what drew me to it was the people I worked with and the energy of making something out of nothing,” he said. “That was what made me interested in newspapers, getting the right creative heads together. That was my beginning.”

Finding Direction Through Liberal Arts

Discussing their college years at Lawrence University individually, both Eliot and McKenzie sound of like mind.

McKenzie said he didn’t have any specific thoughts for his future other than a vague notion that he would like to write.

“Lawrence gave me the confidence that I could be a writer, but I had no confidence in that skill coming out of high school,” he said, adding that he blames himself and not his K – 12 education.

“I did not pick up the fundamentals in K – 12,” McKenzie said. “When I managed to get into Lawrence after spending some time in community college, I worked really hard and realized I can write. This liberal arts education and the way it engages the thinking muscle, the philosophical muscle, the visioning muscle is really exciting.”

“I chose a liberal arts school like my dad had before me,” Eliot said, “because the education was supposed to present itself and through learning I was supposed to figure out the right path. I felt through education I was given all these opportunities, but high school wasn’t enough to tell me what to choose. College was supposed to give me enough variety to tell me that. But I goofed off a lot in my freshman year.”

Luckily, his adviser noticed that Eliot wasn’t achieving his potential, and his adviser just happened to be Lawrence President Richard “Rik” Warch.

“He called me into his office and said ‘You know, I had the same problem. I goofed off a lot, too.’”

Warch advised Eliot that he needed to engage himself in activities.

“So I thought, I worked with the newspaper before. Hey, what’s going on with the newspaper? It turned out the editor got kicked out and there was a sports writer and that was it.”

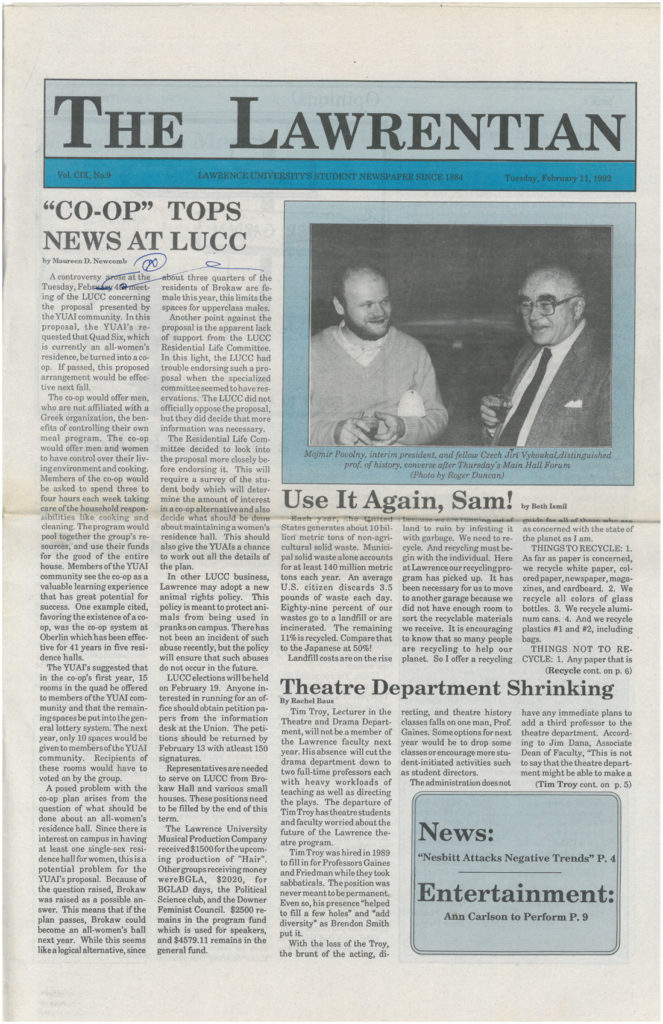

Eliot, a sophomore at the time, was offered the job of editor of the student newspaper, The Lawrentian.

“And then I went and looked at the office. They had computers worse than what we had used at my high school,” he said. “So I went to my adviser and asked if we could get better computers. He said, ‘I’ll put you in a room with someone who might be willing to donate the money.’”

Dave Eliot helped both his high school newspaper, The Governor, and his college newspaper, The Lawrentian, enter the digital age.

Eliot put a proposal together requesting $5,000 for the equipment needed to put together a newspaper, and found himself in a room with Fox Valley architect/philanthropist Frank Shattuck.

“He wrote me a personal check for the amount of money that I asked for and I gave it to the school,” he said. “We got new computers and we made The Lawrentian into a digital newspaper.”

But Eliot learned an important life lesson in his encounter with Shattuck.

“I never wrote Frank a thank you note. Two weeks later — I’ve told this story to graduating seniors — I got a note from Frank. His response was, ‘Don’t bother writing a thank you note, it’s too late.’ Whenever someone gives you money or anything, the right response is a thank you.”

Eliot immediately faced another dilemma.

“I didn’t have a staff and I couldn’t write it myself,” he said.

So he went to all the campus groups and asked them to submit to the newspaper.

“Just give us information and we’ll print it,” he told them. “So I recruited that way. When we started, I had one sports editor and by the time I left, we had 60 different people contributing to the paper.”

Eliot also had an early experience in negotiations while serving as a college editor. A conservative group on campus approached the administration with demands for a budget to start their own newspaper because they didn’t like the views being espoused in The Lawrentian.

That’s when Eliot had to explain that under his direction, The Lawrentian was funded by its advertising rather than by the college.

Then he told the conservative group they could have their own column.

“Write something and participate. We don’t publish you because you don’t submit anything,” he said. “So we got a conservative column. And it worked.”

While Eliot was making the campus newspaper vital and bringing it into the new digital age, McKenzie was contributing to the campus lit/art publication, Tropos.

“I had worked a little with Dave at The Lawrentian. I submitted a couple stories when he was editor,” McKenzie said. “What Dave did that was really remarkable because it gets to a kind of Malcolm Gladwell place, the people who exhibit success are at the right place at the right time. Dave converted the campus paper from cut and paste to digital layout design, which in those days was brand new.

“Dave attracted a circle that enjoyed questioning and pushing things further,” McKenzie continued. “He’s a very visionary guy. He would always be really fun to philosophize with, whether it was something substantial or not. So we connected on those levels and really enjoyed talking and thinking different perspectives on things that were being presented in our academic curriculum.”

All of which set the stage for the next chapter in the two young men’s lives.

What’s Next?

The big reality check of graduation day was coming fast.

“When it came to this conversation of what do we do next, the first big idea that came to us was to purchase a hotel in India and run it. Take our skills we got in Door County and import it to another country,” McKenzie said. “We kind of came down from that idea to something a little more pragmatic.”

“It was a possibility,” Eliot said of the hotel idea. “We had lots of friends in India. We were also going to start a coffee shop. We had the location picked out and everything.”

Ultimately, they decided starting a newspaper in Door County would be the most fun.

“Let’s take these skills — writing, publishing and engaging in the creative arts and other knowledge of community we’ve built up, let’s start a newspaper. Go where we would go anyway, back to Door County,” McKenzie said.

“I said ‘Why not?’” Eliot said. “At that point the technology was moving at a fast rate to make newspapers. We thought, no one else is doing this. Having been in that community, everybody’s talking to a different audience, a 35 to 50-year-old audience, and even within that, no one’s talking about the rich art and music performed. At that time there was music everywhere.”

That was the summer of 1995. McKenzie was dispatched to Door County to find a place for the pair to live and Eliot went home to Ipswich, where his job was to come up with the necessary computer equipment.

“I taught sailing that summer and lived in a tent outside of Ephraim with a friend of mine. It was great. I was celebrating being done with college,” McKenzie said. “As summer went on, I did locate a place a month or so after Dave was going to be out, way out on the edge of Newport Park.”

“I went home and lived with my parents and worked at a restaurant and saved money and took a small loan from them to get a computer and a scanner and a SyQuest drive and moved to Door County in September of 1995 to start a paper,” Eliot said.

This is the home on Juice Mill Lane in Ellison Bay where Dave Eliot and Tom Mackenzie spent the winter of 1995 planning the beginning of the Peninsula Pulse. Submitted photo.

They both had jobs that winter, but when not working, they were planning for their newspaper.

“Where we lived was a quarter-mile from the nearest plowed road, so we would ski out. It was a really severe winter,” McKenzie said. “We lived in a converted structure that was more the way you build a garage than a house. Concrete slab with cedar and flooring installed over that. A woodburning stove was the primary heat. You could really get toasty. We lived with a St. Bernard. It was beautiful.”

The pair wanted to model their newspaper on edgy big city publications such as The Onion, Boston Phoenix, the Village Voice, and Chicago Reader.

“Dave had stacks of publications and we would look at the way they laid things out,” McKenzie said. “Through that first winter we really came up with the concept and layout and design, who we would get for initial contributors, getting some copy together.”

They were also coming up with the newspaper’s philosophy.

“We thought that Door County was known for the arts, for the theater and natural beauty, but underneath that was this service industry that worked their asses off by day and into the night,” Eliot said. “No one was telling what they were doing. And there was all this music happening in all these different bars. And all these cool artists that no one was talking about. Why don’t we tell people where to go to hang out and listen to good music and see great art? There was no one talking to anybody between the age of 20 and 30. They were talking to a different generation. This is an artistic, creative community and people weren’t being literary. They weren’t pushing the boundary of what’s happening. We had all these friends that were literarily inclined with no jobs, 21, 22 years old. I’d been getting people to write for free for years, so why not keep trying?”

The first thing you need when you start a newspaper is a name that people will remember, like The Times-Picayune or The Toledo Blade.

Or the Peninsula Pulse.

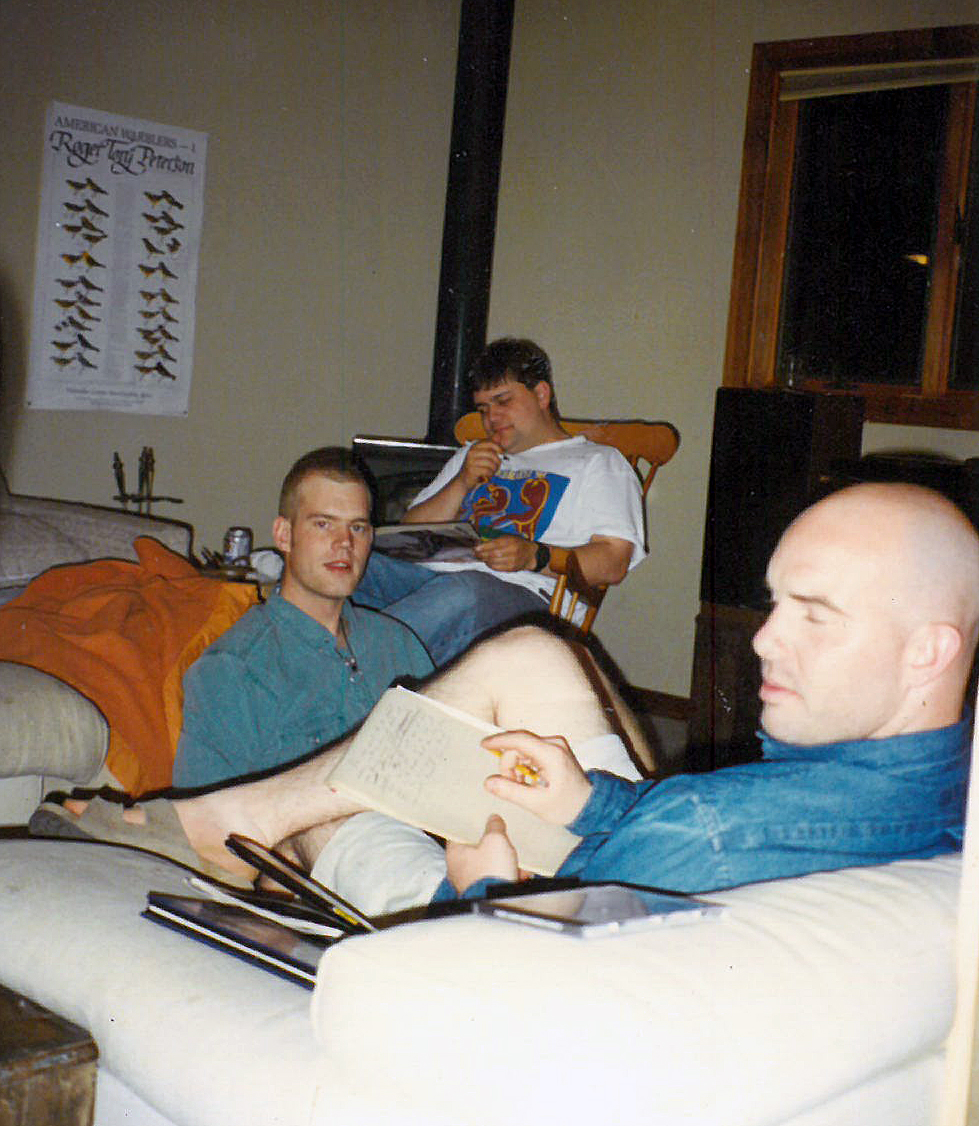

Publisher David Eliot (center) holds an editorial meeting with Neal Gallagher and Chris “Fuzzy” Hanaway.

“The name was a long conversation,” said Tom McKenzie. “We really liked the alliteration and we liked the possibility with the graphics. We actually made a coffee table that was a double P, out of plywood and iron pipe. At the end of the day, we had a list of a dozen names. I have no idea what those other ones were. This one made us laugh and smile the most and stuck in our brains the most.”

After the long winter of plotting their publishing future, Eliot and McKenzie launched Volume 1, Issue 1 of the Peninsula Pulse on May 24, 1996. It was an eight-page edition with five ads. It promised “a comprehensive entertainment section, along with features, opinions, sports and a forum for a wide variety of artists.”

That first issue included a column titled “Subway Evangelism,” written by Don “Cheeks” Jones, whose column mug showed him in mortarboard and gown; a kayaking column called “Wet Exit” by Phil Arnold; a golf column called “Greener Side” by Chris “Fuzzy” Hanaway, in which Fuzzy “reviews the door’s pesticide ridden golf courses”; a featured band of the week (The Brooker Band); four poems; a short story; and a review of Tom Robbins’ novel Half Asleep In Frog Pajamas.

“Poetry in a newspaper? What is that doing there?” Eliot said. “The point was, why limit yourself on entry points to the publication? The point is to get as many people to pick it up as possible. If they identify with one thing, hopefully it will draw their eyes to the 30 other things in there. We had Ellen Kort [the late Wisconsin Poet Laureate from Appleton] writing poetry in the beginning. We had really good poets right away.

“We thought the literariness of it would grow,” Eliot continued. “The more people got their hands on the Pulse, the bigger it got. That’s what we thought, if you find a way to just keep presenting an ideal, people love other people’s stories. You find attachments to different pieces of other people’s lives and the commonality that links you together. How can we connect with all that stuff? It was, ‘Hey, we think we can find voices people will connect with.’”

“The paper was founded on the entertainment section being a thing,” McKenzie said. “We were publishing the philosophical musings of our college friends in the first few issues. It was all really fun to read. The entertainment listings are what people wanted. ‘I’m here for the weekend and I want to have the best time possible.’ When we moved from that to the gallery guide, I think we matured into connecting with a broader cultural community.”

Kafka the Weimaraner appeared on a 4th of July cover. Kafka also served as the ‘Pulse’ logo for many years. Photo by Dave Eliot.

Eliot will be the first to tell you that neither he nor McKenzie were business minded.

“None of us had a business background. All we knew, we had to balance a checkbook,” he said. “OK, if we can keep enough coming in to pay for this and maybe pay our rent. The money we make at our other jobs allows us to experience this place and tell those stories. The idea of a business plan, something was put together but it became more a fly as high as you can, but don’t get your wings get clipped. We never wanted to get in so much debt that we couldn’t get out of it, but we wanted to push the boundaries as much as we can. Both of us were working at other jobs 40 to 60 hours a week and putting out a newspaper on the side. You can say we were young and dumb, but we were young and had energy. Some of our days could be 20 hours long and it was OK. The excitement we got out of that kept us going.”

The first issue contained five small ads.

“The Peninsula Players advertised with us right away because of the family connection [to Tom McKenzie; see Part 1 for details], but I’ll never forget people like Jacinda Duffin and her family,” Eliot said. “She and her sisters owned the Village Café [in Egg Harbor] and were one of the first advertisers. They worked really hard in the restaurant, and they were part of the service industry. They understood we were trying something new together.”

“All the logistics was cultivating relationships we already had with the restaurateurs, barkeeps and small business owners we knew from being up there, and the cultural community I knew,” McKenzie said. “We built up from that, trying to get to know everybody else who was trying to make their mark in the tourist market. If we got to know them and we liked their product, we could help them communicate to the audience.”

And they could do that through the desktop publishing model of newspapering.

“We were offering free layout and design and a pretty low-cost ad. You could get a small, designed ad in the paper for a nominal fee,” McKenzie said. “‘Hey, just give it a try.’ That allowed us to build. We weren’t going after the big fish. We inverted the model. We worked with as many people as we could at as small a level as they were comfortable with. The bigger advertisers will come when they see the infrastructure is in place.”

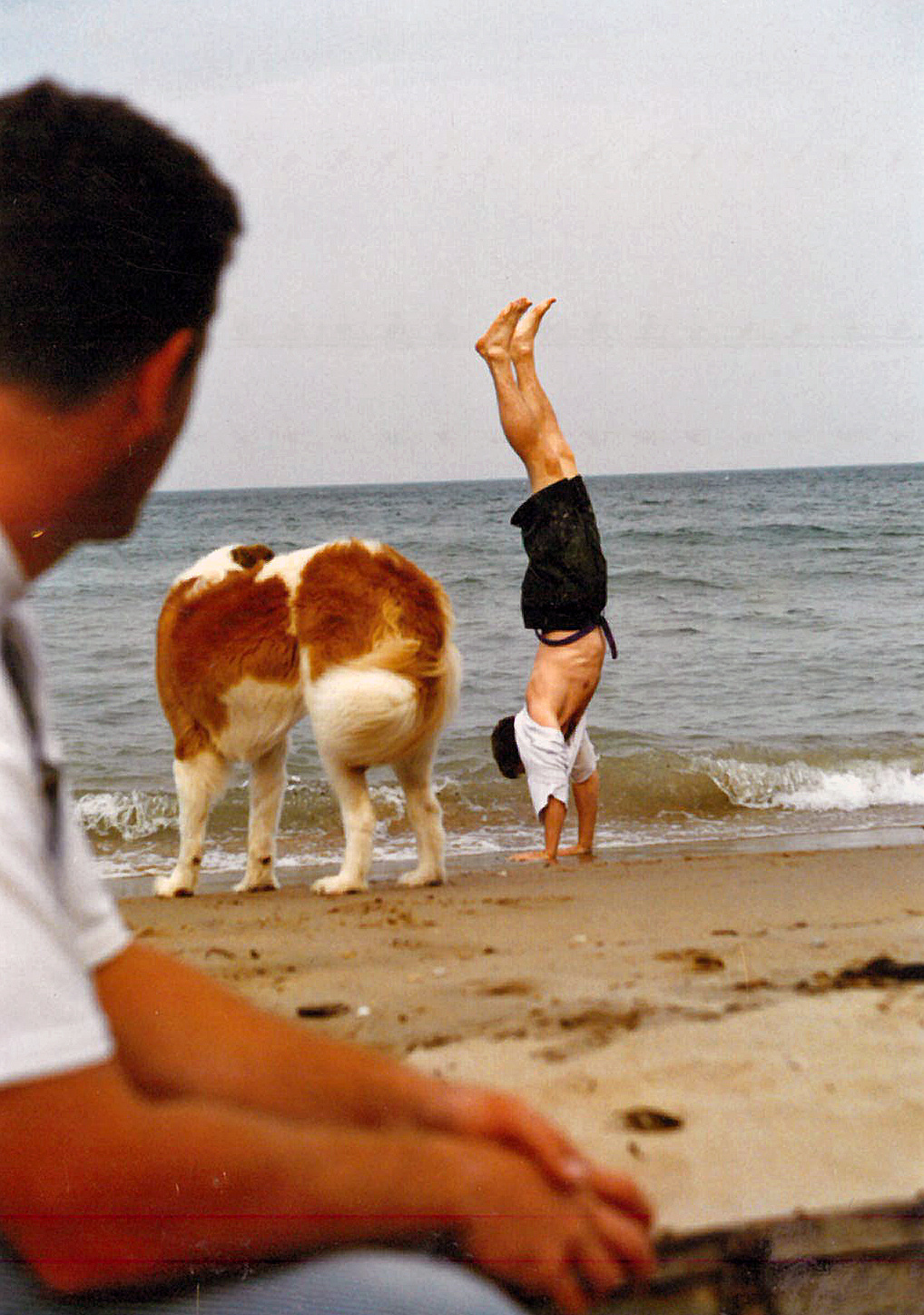

Tom Mckenzie doing a handstand on the beach was used not only as a cover photo, but also for Pulse promotions for years, with the caption “Turning the county upside down.” Photo by Dave Eliot.

‘We Need Food’

One of those early advertisers went on to play a significant role in the newspaper’s history. On page 18 in the August 15, 1997, issue — year two of the Pulse — a full-color ad for Dano’s Peninsula Pizza appeared.

“My brother [Daniel] and I started a restaurant when I was 16 to help us pay for college,” said Myles Dannhausen, Jr. “It was growing and growing. One day I came across the Pulse. I picked one up and thought, somebody’s doing this thing in Door County that is kind of funny with local inside jokes, a bunch of young guys. I called them and said, ‘I’d love you to drop these off at our pizza place.’ As a young kid and local, I thought this actually sounds like the community I know. It connected with me more than anything else I’d been seeing.”

One fateful day, Dave Eliot and Tom McKenzie showed up at Dano’s.

“I said I’d like to advertise, but we didn’t have an advertising budget,” Dannhausen said. “So they said, ‘We need food. How about if we trade an ad for pizzas?’ So that’s what we did. I would deliver pizzas to them. It was like five days a week they would be getting pizzas. That’s when my brother said, ‘I wonder if this trade is working out for us?’”

Little did the two newspaper entrepreneurs know they were making a connection that continues to this day.

Dannhausen grew up getting off the school bus to dig into his grandmother’s Chicago Tribune sports pages.

“I always saw myself becoming a writer, a sports writer,” he said. “At some point, Dave asked if I would want to write a sports column. It was always late, always missing deadlines, setting a precedent for the rest of my time at the Pulse.”

After attending Madison to become a sportswriter, and then being around actual sportswriters, Dannhausen decided it was not how he wanted to spend the rest of his life. But he wasn’t done with writing or the Pulse.

The Wonderful World of Color

Right from the start, the Pulse added color to its world, with color front pages, inside photos and ads.

“That was a radical step,” McKenzie said. “I credit Dave for that. It invited you to grab it first before anything else on the counter.”

“It wasn’t perfect in those early days. You can look at it and the plates didn’t line up,” Eliot said. “But we were one of the first to bring color to Door County and showed that it could be done.”

The first cover of the second year, on May 23, 1997, not only featured a color photo, but it began a relationship with photographer Dan Eggert. Like McKenzie, Eggert was from Appleton. The pair met in junior high school.

Eggert made his first trip to Door County in 1996 during a camping trip to Rock Island. McKenzie knew about Eggert’s interest in photography, so asked for some of Eggert’s photos of his Rock Island visit.

“Next thing I know, the Pulse comes out and there’s me on the cover from the Rock Island trip,” Eggert said. “It was pretty funny. That was kind of the start of it for me. Things just rolled from there.”

The next year, Eggert was asked to be the Pulse photographer.

Sunrise at Cave Point. Photo by Dan Eggert.

“He took photos and became a dear friend,” Eliot said. “He was self-educated in photography and I was somewhat self-educated in newspapers. Let’s take this common interest and keep doing what you’re doing.”

“They couldn’t afford to pay me,” Eggert recalls. “We had a trade out with Peninsula Photo Imaging. I would get three rolls of film and free developing for each issue. That was my payment at the time.”

That situation eventually changed during Eggert’s 14 years with the Pulse, but there were other benefits of the job that he is grateful for.

“It really helped develop my photography skills,” he said. “It gave me the freedom to go out and get photos. It really developed my eye. And when it came to Door County, I got to meet everybody. I met all the artists and business owners, either through photography or delivery. That was probably the biggest benefit. This is home to me.

“It was a great experience,” Eggert continued. “The Pulse is what made me who I am today when it comes to photography. Without that, I would probably be an amateur photographer doing it for a hobby. If it wasn’t for the Pulse, I wouldn’t be in galleries right now. The gallery owners know me from that. It was such a big part of my life.”

Although Eggert considers Door County home, it is only his summer home. For the past dozen years he has spent the winter in Lake Tahoe. At one point, he was considering moving to Lake Tahoe year round. After 14 years with the Pulse, Eggert decided to move on and recommended fellow Door County photographer Len Villano to replace him.

“I was ready to move on,” Eggert said. “It helped me build where I am today, so I’m very grateful for everything that happened. It was time after 14 years to move on.”

Exit Tom McKenzie

Incrementally, issue by issue, as McKenzie was out delivering the newspaper or gathering ads, he felt credibility growing for the young publication.

“We were growing on instinct and perceived demand, and a real ambitiousness that paid off,” he said. “Every issue was bigger than the last. And those first five years, every year we did something bigger than the last year. I’m not sure when we reached 10,000 copies, but that was a milestone. We were probably doing that by year two or certainly by year three. That became a major milestone. It seemed like an ambitious push and almost frightening, but one that paid off. I credit Dave for pushing that ambitious target and having the vision for it.”

Another milestone McKenzie mentions is deciding to have an annual literary contest of poetry and short stories.

“I always wanted to figure out how we could run more literary work, like you would see in the old Saturday Evening Post, when they would put in a chapter from an emerging novelist’s work,” McKenzie said. “Both Dave and I wanted to figure out how to frame that. The literary contest was a way to do that.”

Both McKenzie and Eliot had come to know Hal Grutzmacher through his then endeavor as owner of Passtimes Books in Sister Bay. But Grutzmacher was also a respected English professor and academician.

“When the Pulse was getting started, Tom McKenzie would come and visit my dad or I to pick our brains and bounce ideas off us,” recalled Hal’s son, Steve Grutzmacher. “When Tom delivered the paper, he would hang out and find out what we thought of it.”

When Hal died in 1998, McKenzie asked the Grutzmacher family if the Pulse could run a literary contest named for Hal, and that year the Hal Grutzmacher Prize was born (now known simply as the Hal Prize).

“The Hal Grutzmacher literary contest was a major milestone for us,” McKenzie said. “No. 1, his death was an event in the community, and I connected with Hal at the store a lot. We were able to recognize a community legend and give readers and all the contributors something really exciting. We found a lot of voices that maybe were never going to be seen or heard by anybody else.”

Around the turn of the century, Eliot began thinking about the next big push for the Pulse — going year round.

“It was always something we were going to do,” he said. “We both decided to make a living with this. It wasn’t just going to be a hobby.”

“Dave decided the next push for the paper was to go year round, which was bold,” McKenzie said. “That turned conversation into turning the editorial position and outreach from a tourist market to the community at large. Right about this time, The Advocate was bought up by Gannett. We hadn’t even grasped the ramifications of that, but it did set up the Peninsula Pulse to be the locally owned and operated publication of Door County. And it opened up something to what Dave and I talked about for a long time, attending town meetings and real community journalism. We just didn’t have the resources in the beginning.”

“I was opening a coffee shop in the morning and waiting tables at night, so how could I do an in-depth story?” Eliot said. “Tom was doing the same exact thing. If we decided to go into that kind of journalism, it wasn’t sustainable at that time. It was trying to find the right people to do it. It had to be people with the same passion because we didn’t have the resources.”

Meanwhile, people were growing up and thinking about their circumstances.

David Eliot and Tom McKenzie with Eliot’s parents, Larry and Charlotte Eliot.

“It was a little club for a while. It didn’t matter if we stayed up all night to put it together and then drive it to get printed and then go to work. You didn’t get crabby at anybody, because it was fun,” Eliot said. “But as you grow up, people are pulling you in different directions. That put other outside stresses on this thing. In 2001, we both started to feel those pulls. We said, this is the year we’re going to make a go of it.”

But at the end of the 2001 season in Door County, McKenzie packed up his pickup truck, attended a friend’s wedding in Florida and then drove cross-country to Los Angeles where his girlfriend Jill, a Sturgeon Bay native, was attending art school.

“I remember thinking I might be back next summer. But I wasn’t fixed in my mind either way,” McKenzie said. “I had a lot to deal with when I got here and I didn’t have a set plan other than to stoke the flames of this relationship with Jill and just survive, but knowing that I would be happy to go back to Door County if it doesn’t work out.”

But it did work out. Fifteen years after leaving Door County, Tom and Jill are married and he works as a development manager for the Los Angeles County Arts Commission.

“As soon as he said he’s leaving, I said, I’ve got to get serious,” Eliot said. “There was a mutual understanding that if I’m working, I’m going to get paid and you’re not, but it’s here if you want it. I never viewed it as, Tom’s leaving and it’s mine now. There was always the idea that he might be back.”

While McKenzie said he misses the Pulse, he’s also happy with his life and proud of what the Pulsehas become.

“The thing I’m most proud of at the Pulse, it’s providing a good livelihood for people in the community and telling a good story about the community. Now it’s a shop that employs a lot of people, and people who formerly did have careers in the older model,” he said. “I love the Pulse and I’m very proud of it.”

When David Eliot’s business partner Thomas McKenzie left the Peninsula Pulse in 2001, five years after it started, it only made him more determined to see the upstart publication succeed.

“It was more stubbornness that kept it going,” he said. “I wasn’t looking at numbers. I wasn’t analyzing the publication from a financial standpoint. Some people said I couldn’t do it. That’s when I dug my heels in.”

Unwittingly, McKenzie developed a connection with an adventurous young woman named Madeline Johnson, who was introduced to Door County as a child by her parents.

“My dad used to come here as a kid and my parents honeymooned here in 1968,” she said. “My parents were workaholic types when we were young. They decided when we were little, they would come to Door County religiously once a month, a six-hour drive each way. Most of our family time was in the car coming up to Door County. We would come up for a week or two in the summer. Door County always felt like home to me.”

The summer of 1998, before starting her senior year in college, she came to Door County to work.

“I taught sailing and did some other odd jobs, and I was bitten by the Door County bug,” she said. “That first summer I worked at the Ephraim sailing center, and worked with Tom McKenzie. Tom and I became buddies right away. Tom being Tom, he was always, ‘Hey, can I borrow your car to deliver some newspapers?’”

It soon went from Tom borrowing Madeline’s car to Madeline and her friend delivering the Pulse on Fridays.

“That’s kind of how I got started,” she said. “Shortly after that, Tom had pushed me into doing a little bit of writing. The next summer I started writing a little more, helped deliver papers and started doing the events calendar. I think that made up a lot of actual content.”

She stayed through the fall that second year, and then headed west before returning to Door County for a summer/fall/winter before going to South America for a year.

Which brings us to 2002. The year after Tom McKenzie left to pursue his dreams in California, Madeline returned to Door County.

“I used to joke that Door County has a magnetic field and it kept sucking me back,” she said.

Meanwhile, Dave Eliot had taken a marketing job with John Nelson’s Open Door Communications.

“He was fine with me doing this [the Pulse] on the side. It kind of coincided,” Eliot said.

Recognizing the valuable organizational and business skills Madeline could bring to the Pulseoperation but knowing that he could not afford her, he got her a job with Nelson’s company.

“John Nelson said, ‘If you pay half of Madeline’s salary I’ll pay the other half,’” Eliot said. “I took half of what I made and gave it to Madeline so she would work for me.”

“I wanted to do it,” Madeline said. “I knew it was not a get-rich-quick scheme, but it was a cool thing to be doing. I was 24, 25 at that point and I thought, this has a lot more heart and soul than any other thing I could be doing.”

This also marked another major turning point for the organization — managing a payroll.

“It was all contributors until early 2002 when Madeline and Roger Kuhns joined,” Eliot said.

Today Roger Kuhns is well known as a speaker and writer on topics that include the environment and the Niagara Escarpment. He’s also a musician, entertainer and thoroughly genial character. But Dave Eliot describes him better.

Madeline Johnson (now Harrison) and Roger Kuhns at Leroy’s Water St. Coffee, a Pulse hangout.

“And then Roger Kuhns came in as this Indiana Jones guy, been all over the world, done all these things, had a great education. He used to do presentations that would have made some rock concerts seem small. He had a cult following.

“Roger drew up this big business plan,” Eliot continued, “then Roger got elected to the county board and the newspaper started having these conflicts of interest questions. The county board called us into question — if somebody is on the county board and writing about it, that’s a violation of ethics.”

Kuhns recalls a Frank Capra-esque moment, with Eliot using the ethics accusation as a lesson in democracy.

“Dave Eliot said, ‘This seems to restrict public dialogue, which is the foundation of a democracy, and for creative ideas for solving our world’s growing problems,’” Kuhns said. “Dave was great. He and I sat side by side in the Administrative Committee meeting, and he held his ground.”

While Kuhns and Eliot were setting a course for the Pulse as a news source, Madeline, who had been willing to do whatever needed to be done, including delivering the pages to the printer in Kenosha, saw a new way to pitch in.

“By spring of 2002 it was pretty clear I needed to go out and sell ads and get involved in the business side of things to help keep things moving. We had to wear a lot of hats,” she said.

Selling was new to her, but she jumped right in.

“My dad’s a really great salesperson. I think I take after him a lot. I’m an assertive personality,” she said. “What Tom and Dave started, they got it from absolutely nothing to the point where I came in. I don’t want to diminish that hard work. I guess there was a certain desperation, too. I wanted to get paid. We all needed to get paid. The printer had to be paid. We had to keep the lights on. I felt there wasn’t really a choice about it, but I think I had some natural personality traits that helped make it work. That was fun, too. I actually enjoyed a lot of that. You get to meet all the Door County characters. A lot of those first customers from those first years are my best customers. They’ve really stopped being customers and have become friends.”

Kuhns eventually left for a job that offered more money, “but I do miss working with that great team,” he said, adding, “From me, a huge thank you to the Pulse, especially for Dave’s vision and Madeline’s incredible work, and everyone else from those days up to now.”

Kuhns’ departure left a newswriting gap at the Pulse, but an industrious young Egg Harbor man who had become a fan of the newspaper in the beginning soon would make his mark on the Pulse.

“One day I came across the first issue of the Pulse,” said Myles Dannhausen, Jr. “I picked one up and thought, somebody’s doing this thing in Door County that is kind of funny with local, inside jokes, a bunch of young guys. As a young kid and local, I thought this actually sounds like the community I know. Even though it was just an eight-page flyer, it connected with me more than anything else I’d been seeing.”

At the time, Dannhausen and his brother were running a pizza place in Egg Harbor. He called the owners of the Pulse and said he would like to have them drop them off at the pizza place for their customers.

“Tom and Dave came down. I told them we’d like to advertise, but we didn’t have an advertising budget,” Dannhausen said. “So they said, ‘We need food. How about if we trade an ad for pizzas?’ So that’s what we did. I would deliver pizza to Dave and Tom. It was like five days a week they would be getting pizzas. That’s when my brother said, ‘I wonder if this trade is working out for us?’”

But Dannhausen, whose first ambition had been to become a sports writer like the guys he read regularly in his grandmother’s copy of The Chicago Tribune, loved what they were doing.

“All these guys trying to crank out a little paper on crappy old computers. The office was just a mess because everyone was working one or two other jobs,” he said. “At some point, Dave asked if I would want to write a sports column. I was always late anyways, missing deadlines, setting a precedent for the rest of my time at the Pulse. It started a long tradition of Dave hounding me for stuff.”

Eventually they started offering Dannhausen money to write a couple of news stories or a feature or something on music or nightlife.

“I thought, ‘Wow, I’m going to these things anyway and they’re going to pay me,’” Dannhausen said.

But he wasn’t making enough money to live on, and he felt the world calling. He decided to take a break and head out west.

“I spent three months just driving around the west, trying to figure out the next step,” Dannhausen said, adding that he was considering moving west to attend college and pursue a political science degree. Then he heard from Dave Eliot with a proposition for him.

“They cobbled enough different roles together where I could come back and say this is an opportunity. If they hadn’t done that, I would have stayed out west. I’m glad they did that.”

Myles Dannhausen, Jr., leaving the Pulse office in Baileys Harbor to cover a story.

Dannhausen dug in and started reporting news, but often found himself having to explain the Pulse to people.

“The Advocate was the paper. And the Pulse was an artsy-fartsy kind of thing. That’s what most people would say,” Dannhausen said. “So when I started calling people up about news, say for a zoning issue and stuff, it was hard to get people to call back because a lot of people didn’t know what the Pulse was. I’d go to a meeting and they wouldn’t acknowledge me, but then someone from the Advocate would come in and they’d say, ‘Oh, good, we’ve got the paper here.’ So that was hard.”

But, suddenly, as he kept plugging away at hard news, people started calling back.

“There came a time, too, people started reaching out to me with story ideas, town board members, concerned citizens, village presidents, seeing us as the ones to take on an issue or tell the story,” he said. “Suddenly people are saying, you should write about this news topic.”

Dannhausen recalls another big turning point, when he took a call from well-known Door County naturalist Roy Lukes.

“He told me that he was looking at leaving the Advocate because he didn’t like Gannett and was wondering if he could come to the Pulse and would we be interested,” Dannhausen said. “You would always see his picture in the paper. He was part of old guard, respected Door County. I got off the phone and was excited and thought, we must be legit if people want to leave Gannett and come to write for us. It was great that we were seen as an alternative.”

From 2003 to 2011 Dannhausen made his mark on Door County with stories that appeared in the Peninsula Pulse and Door County Living (the monthly magazine was added to the fold in the 21st century, but that is a story for another time).

“What was good, it’s great to work for people who have your back,” Dannhausen said. “Dave and Madeline always gave you the benefit of the doubt and had my back. If they didn’t, maybe I would have been afraid to write certain things. Knowing that they would take your side from the get-go, it gives you a lot more confidence to keep taking stabs at it.”

In 2012, Dannhausen moved to Chicago where so many of his Door County friends had moved and where his sister and nieces and nephews were.

“I thought I would sever ties with the Pulse, or I thought I might write things but not at the level I still do,” he said. “Those guys are hard to sever. My parents are still there. I still have a lot of friends there. I feel there are so many stories in my head that I still want to write about up there, I still care so much about the community. Sometimes I wish I could let it go more, but I haven’t been able to.”

In 2004 a recent college graduate with a degree in English and philosophy snagged a summer internship with the Pulse that turned into a full-time job.

“This is one of those stories about how in Door County we get to play by different rules. It’s not the same atmosphere that corporate newspapers face in big cities,” said Allison Vroman, who began as a Pulse summer intern in 2004 and advanced to editor before leaving in 2012. “Dave and Madeline were looking for ways to grow the paper and they took a smart approach through planning to do that. Not biting off too much, taking things incrementally. Increasing year to year, rather than trying to make the leap in one fell swoop. I think they were very wise in how they moved forward.”

Vroman’s first experience was copywriting and writing a column as an intern. After that season, she spent the winter in Colorado, and was then hired by the Pulse as a staff writer, eventually progressing to editor, and seeing the Pulse become a more professional newspaper along the way.

“Thinking back to my first staff meeting to my last, the ways in which they were able to fine tune the process without losing any authenticity is what I was most impressed with,” she said. “The paper really has paid attention to its audience over the years and the growth of that audience has allowed the paper to grow. The original intent was an alternative news and entertainment source. Over the years, the community was really looking for someone to fill more of the mainstream niche. I think the Pulse was able to fill that void without losing its identify or its independence or original unique flavor of what Door County is or what it should be.”

Office dog Otto on the Peninsula Pulse “P” table.

People have come and gone in the first 20 years of the Peninsula Pulse, but the mission to provide news and entertainment for the people of Door County remains the same.

“I could never anticipated any of this,” Eliot said. “The path started and I just followed it. This is what I do now. We choose to take certain steps in our lives and it’s really hard to change the path. I don’t regret any of the steps I’ve taken and I look forward to what’s coming up. I have been introduced to all sorts of interesting people and I always think there is a way we can be better as a newspaper, as a website, as a delivery company, and as a contributor and participant in our community. To me it’s satisfying and fun to serve our community. I was raised on the idea that it’s not about how much money you make, it’s what you contribute and give back to your community. That is what Door County is all about, a community that takes care of one another. It’s what keeps people coming here. It is an honor to be a part of it.”

•••

The Next Chapter

In the last 20 years the Peninsula Pulse has seen many incredible people on its pages. It continues to be a pleasure to work beside so many talented people. Many great memories have been brought back sorting through old photographs while reflecting on the history of the publication.

It was and continues to be an adventure we look forward to every day.

The Door County community took a little while to warm up to our little rag of a newspaper in 1996 and we had our growing pains. When Tom McKenzie and I first dreamed up the idea of a publication, we never imagined what it is today. All the people that have passed in and out of the Pulse’s pages and through the office doors have taught me so much and we owe so much of the business’s growth and personal growth to them. We are deeply grateful to each and every individual who at one time or another contributed to the publication.

Over the last 15 years there has been one constant in the operations, growth and emergence of the Peninsula Pulse — Madeline Harrison. She started delivering papers, went on to manage the events calendar, write articles and then became my business partner in 2003. She and I have puzzled through some tough challenges and weathered a few storms. It has been an honor to work with her and the paper has grown exponentially under our collective watch.

2017, however, will be the beginning of a new chapter of the publication. Madeline Harrison is leaving the Pulse to pursue her next adventure. She is looking forward to what the world will offer beyond the editing and deadlines. It is hard to imagine the office without Madeline in it, but we wish her the best and owe her a great debt of gratitude.

Madeline has helped build a strong foundation for the Pulse and as the page turns to the next chapter we will continue to grow and evolve and find even more ways to deliver the news, events, and stories of Door County to the community that we love.

Thanks for reading.

David Eliot

Publisher, Peninsula Pulse