Chief Roy Oshkosh: Door County’s Unlikely Ambassador

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

Sounds of pounding bare feet, drum beats, and the crackling of a bonfire all speak of an era of Door County tradition gone by, but the experience, and the man behind it, are not forgotten. Chief Oshkosh’s powwows in Egg Harbor are one of the most memorable traditions for those who can recall the peninsula 50 years ago.

Chief Roy J. Oshkosh was a man in search of his place in the world when he came to the Door Peninsula in 1939. World War II had brought him and his electrical engineering skills to the Leathem D. Smith shipyard in Sturgeon Bay to build war ships. It was then that he began seeking out a dream and a place that his grandmother had told him of many years ago.

“His grandmother had always told him about a place in Door County where the water flowed through a wooded glen and disappeared never to be seen again,” explains Oshkosh’s stepdaughter Jeannette Hutchins, whose mother Agnes Lindall married Oshkosh late in life. “This was a site where the Menominee had camped. She had told him about this special, special place, and how much she loved it. On his days off, he started driving around looking for it.”

Chief Oshkosh, a Menominee Indian, had close ties to his homeland and reservation; however, he wanted badly to find this unique place that he believed held spiritual power for his people. Eventually, he found it at the base of the Egg Harbor hill. He followed a creek and was surprised when suddenly the water dipped into the earth and disappeared.

“It was originally the Egg Harbor town dump,” Hutchins chuckles. “That didn’t stop him. He made arrangements to buy it immediately and cleaned it up.” He cut timbers to construct what would become his cabin and the Chief Oshkosh Trading Post. Chief Oshkosh, simply called “Chief” by those who remember him well, peeled and hewed his logs and constructed the cabin, which still stands in the same spot.

What he built became more than simply a homestead and a trading post – it was a museum that held historical relics of the proud heritage of Wisconsin’s native peoples, as well as contemporary art. His work in Door County was a mission to preserve Wisconsin’s native history.

After his first season in operation, Chief told Duncan Thorp of the Door County Advocate that “I want to open outlets for the work of my people. Many of them are poor but honest and the sale of their bead and basket work is a big help to them.”

A Rich Heritage

Chief Oshkosh was tied indelibly to the Menominee people. The title “Chief” was by no means an ornamental title; he was indeed the Chief of the Menominee. Roy Oshkosh’s great-grandfather was the namesake of the city of Oshkosh. He is known to history also as Os’koss the Brave, who refused the advances of the Bureau of Indian Affairs to relocate the Menominee people to a reservation west of the Mississippi River. Os’koss the Brave traveled to Washington D.C. in 1850 to plead with President Millard Fillmore for his people’s case. President Fillmore honored the Chief’s request, and the Menominee’s land was made into their current reservation.

Chief Roy Oshkosh would inherit the title of Chief when his own father, Os’koss’ grandson Reginald, passed away in 1931. Roy Oshkosh, whose Menominee name is Tschekatch’ake’mau III, became the head of the Menominee people. Since no children survived him, Chief Roy Oshkosh was the last hereditary Chief of his people.

Chief’s Path to Door County

Before Chief settled permanently in Door County, his travels took him to Pennsylvania, Chicago and back to the Menominee reservation of his birth.

Roy, born on July 13, 1898, was one of four children. As a teen his father sent him to the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania to study electrical and mechanical engineering. Carlisle Indian School, like others of its kind around the country, was believed by Natives and Anglos alike to be part of the American government’s attempts to assimilate and “educate” Native American children in the ways of white culture.

“A lot of people believe that the Indian school was an attempt to Americanize the Indians. However, it didn’t change Roy in his feeling about his people at all,” says Hutchins.

Chief Oshkosh returned to the reservation to begin his duties as Chief of the Menominee by starting a trading post and helping to oversee the Menominee’s growing lumber industry. When the war broke out, Chief left the reservation, but he continued to return when tribal needs required his presence or simply to hunt and fish in his homeland. Pride for his heritage was something that friends and relatives remember most about him.

“In spite of his Carlisle education, he was very, very proud to be an American Indian,” Hutchins explains. “He called himself an Indian. He never called himself a Native American. He never felt that being called an Indian was a put down. His pride of who he was was something that I will never forget.”

This pride came with when he arrived and found that hallowed ground in Egg Harbor. In 1946, he also found his second wife Ruth (his first marriage on the reservation had ended sadly when his son, Pershing, died tragically in a car accident). Ruth Morgan, who became Princess Shawan, worked by Chief’s side for the next 23 years as his closest confidant and business partner at the Trading Post.

Creating Door County Traditions

Nearly 40 years after his death folks who knew him still remember Chief’s feisty sense of humor, which he used often as a promoter of Door County tourism. Chief Oshkosh knew that not only was Door County a unique place, but it was a place that he wanted to share with others. As such, Chief and Ruth often traveled to trade shows around the Midwest to promote Door County with other early advocates like the late Al Johnson.

When he attended these trade shows, he would often dress himself from head to toe in his traditional ceremonial garb, resplendent in his white leather Menominee suit, moccasins, and full headdress. Egg Harbor Town Supervisor Myles Dannhausen Sr. recalls seeing Chief adorned as such and that inimitable sense of humor.

“He would be standing around, talking engineering with my father. Then when a kid would slowly walk by staring at Chief in amazement, he would bend over, return the stare, and say ‘How,’” Dannhausen recalls.

The trade shows, often boat shows, were prime places to attract visitors. His personality drew people to him, as he would tout the wonders of Door County.

“He had so much enthusiasm about things; [the ambassadors] were so well received. People started coming up here because of Chief. He did know how to bring about people’s interest. Truly, he was Door County’s first ambassador,” says Hutchins.

Indeed, in 1971, the Door County Chamber of Commerce honored Oshkosh with a designation as Door County’s number one ambassador.

Others recall similar humorous stories that Chief used to tell to explain some of the causes of suffering American Indians endured. Chief used to say, “America would not be in the mess it’s in today if the Indians had had stricter immigration laws.”

Hutchins recalls the first time she met him. They had stopped for coffee when Chief said, “Did you lock your door? You better check! There are a lot of white people around here.” This type of lively word play was characteristic of the Chief’s sense of humor – and people loved it.

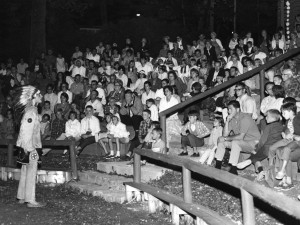

Chief became well known for the powwows he staged at the amphitheater he built in the woods behind his cabin and trading post. The amphitheater remains there today.

Tom Zwicky, a Spanish teacher at Gibraltar High School, and a participant in the powwows from 1963 to 1968, recalls what Door County was like.

“People don’t remember that Door County was different back then. Memorial Day, a little bit of June, and the Fourth of July were all that the six-week tourist season consisted of,” Zwicky says. “Wednesdays, Saturdays, and Sundays, however, people would take their kids to Chief Oshkosh.”

On those magical evenings, families and visitors would gather at Chief’s amphitheater to get a taste of an era of Wisconsin history and participate in a memorable experience that included drumming, singing, dancing, and Menominee ceremonies.

Zwicky, along with other Boy Scouts in the Order of the Arrow, were taught traditional Menominee dances and dressed in native garb to perform for the families that gathered. They were called the Owassie Dancers.

“We wore moccasins, ankle bells, and breechcloths (with no swimming suits underneath). Some of us actually wore things that belonged to Chief Oshkosh; one of us would even wear one of his old leather costumes, and some sort of a feathered headdress and bustles on the arms,” Zwicky remembers.

Chief would begin by telling the story of how he picked the cherished site they were sitting on and follow that with a peace pipe smoking ceremony.

“He had a pipe that was very old and carved of wood and stone. After the pipe ceremony he would turn it over to the drummers, and we would start our traditional dancing,” says Zwicky.

After the dancing and storytelling, all of the children from the audience would be invited up on stage to participate in the dancing. Afterward, he would touch each child on the shoulder with his peace pipe, making them honorary members of the Menominee tribe. For those who were lucky enough to witness such an experience, the impression stayed with them.

Dannhausen Sr. says, “I remember when we used to hear the powwows out back behind the shop. If the wind was right you could hear it all over the village.”

Door County Says Goodbye to Chief Oshkosh

On July 7, 1969 Chief Oshkosh’s wife Ruth passed away. Chief continued working at the trading post and presenting educational information at classrooms and travel shows. In 1970, after a hunting trip to Washington Island, Chief married Agnes Lindall, an island native. Together, they shared their respective heritages with one another and visitors to the trading post.

When Chief suffered from a stroke, and then passed away on April 28, 1974, people paused to remember the man who was so much more than an ambassador for Door County. Hutchins remembered what she loved best about him: “His kindness and sense of humor caused me to fall in love with him, too.”

All who knew him recall what a powerful presence he had. He was many things – a teacher, a husband, an advocate for Door County and for American Indians, and a businessman – but, above all else, he was, and is, an icon.

The Mystery of the  Oshkosh Statue

Oshkosh Statue

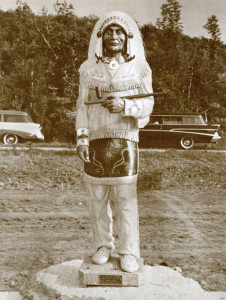

In the early morning hours of July 12, 1973, a life-sized statue of Chief Roy Oshkosh was stolen from its location in Murphy Park, Egg Harbor. While the police investigated the theft for decades, the original statue was never recovered.

An August 1985 Milwaukee Journal Sentinel article cites that “authorities believe the theft possibly supplied a conversation piece for some area resident’s recreation room.”

The statue was originally commissioned in 1958 by a Green Bay doctor named Robert Cowles in honor of his good friend Chief Roy Oshkosh. Professional woodcarver Ernst Dombrowe created the life-size likeness of Chief Oshkosh dressed in traditional Menominee costume and holding a peace pipe.

Today, a replica stands on the grounds of Chief Oshkosh’s Trading Post. In 1985, The American Legion commissioned Michigan woodcarver Jerry Ward to re-create the statue that was so dear to Chief Oshkosh and his family. Visitors can still stop and visit with the replica and pause to wonder what happened to such a prized relic of our county’s history.