Cold Enough for You? Remembering Winters Past

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

After a foot or so of snow was dumped on us Monday, we braced for a cold wave the like of which, we were told, hadn’t been seen in a generation.

How soon we forget the long, bleak winter of 2013-14. That was the winter when the term “polar vortex” entered the lexicon. That winter started early and stayed very late, bringing record-breaking temperatures and seemingly endless snowstorms.

That was also the winter when a variety of factors led to constraints on the propane supply, which led to a spike in prices. Ice formed early on the Great Lakes and stayed late, covering 92.5 percent of open water, which was the second most extensive ice cover on record during the satellite era. Ice on the eastern shore of Lake Superior was 42 inches thick, a thickness normally seen in polar regions. By the end of the first week of March, Lake Michigan was 93.3 percent ice-covered, which set an individual record. Although the Soo Locks officially opened to shipping traffic on March 25, 2014, ice prevented the first freighter from going through until April 4.

So this blizzard and cold snap – destined to end by the time you are reading this – doesn’t seem so bad, but bad weather seems to make us reach for hyperbole.

“Worst Storm in Years Followed By Zero Weather That Goes to Fifteen and More Below,” read a subheadline on the story about a January 1917 blizzard that continued for 28 hours.

Or there was the 30-hour-long blizzard of late February 1913, which prevented the Saturday Baileys Harbor stage to Sturgeon Bay from making the trip and caused a search party to hunt on the ice for an ice boat carrying four high school basketball players from Menominee who were on their way to play Sturgeon Bay when the ice boat broke down in the storm and they were forced to hoof it into the city, where they got a hotel room as the search for them carried on fruitlessly.

Or the early-February blizzard of 1924 that stopped train service to the county for two days and left, according to one headline, “Snow Piled Ten Feet Deep on Roads and Streets.”

Or there was the “April Fool Storm” of 1929, which started on Easter Sunday morning and continued for 36 hours.

Or the late-January 1938 blizzard. “WORST BLIZZARD IN YEARS TIES UP DOOR COUNTY” read one headline.

Or the mid-March blizzard of 1958 that prompted this headline: County’s Worst Blizzard in 20 Yrs. Hits Saturday.”

Or the blizzard of late-December 1968 that dumped 13 inches of snow on top of nine inches from two earlier snowfalls in the same month. A story about that blizzard also refers to 1959, when two blizzards in a row amounted to 30 inches of snow falling on the county.

Let’s not forget the “Great Blizzard of ’78,” which came at the end of January 1978. It was deemed “the worst blizzard to hit Door County in 19 years, claiming one life, paralyzing traffic, closing schools and shutting down most business and industrial activity.” The storm-related death was that of a 69-year-old Fish Creek man who was found frozen in his buried car only 60 feet from his home on Highland Road.

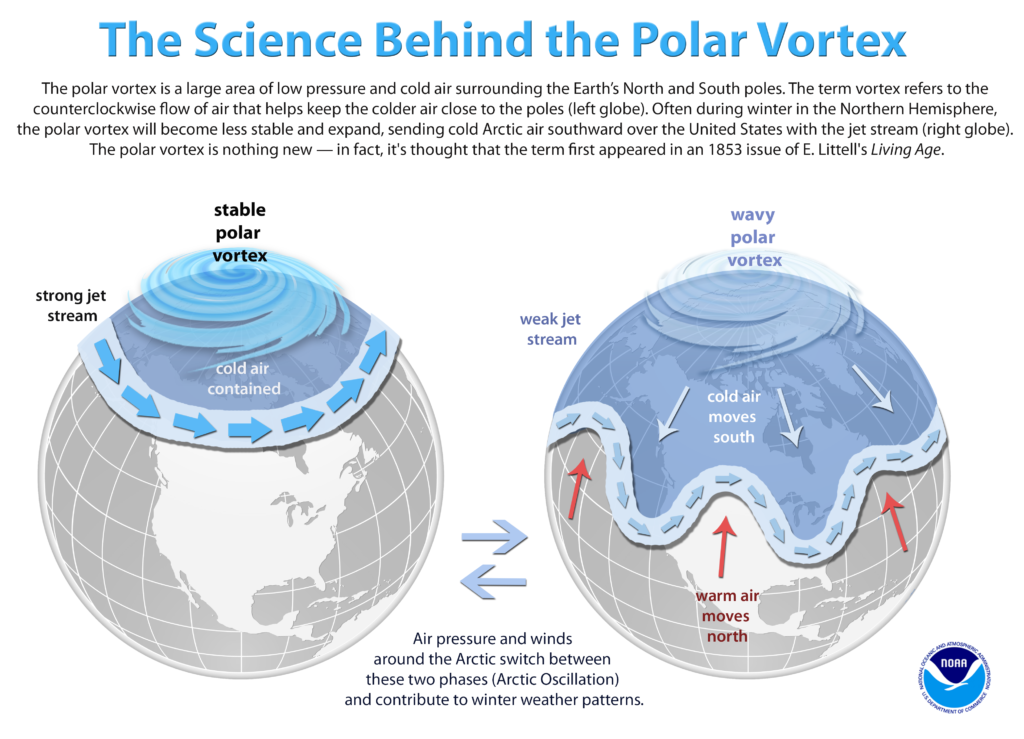

The Science of the Polar Vortex

In anticipation of the polar vortex that was about to descend on a large part of the country, President Donald Trump used the occasion to once again mock the idea of climate change in a Jan. 28 tweet: “In the beautiful Midwest, windchill temperatures are reaching minus 60 degrees, the coldest ever recorded. In coming days, expected to get even colder. People can’t last outside even for minutes. What the hell is going on with Global Waming [sic]? Please come back fast, we need you!”

While he and his base must find that amusing, it shows a basic ignorance of science and why an unstable polar vortex migrates south.

In fact, climate change is one of the reasons for the destabilization of the stratospheric polar vortex.

Greenhouse gas emissions have warmed the Arctic – home of the polar vortex – twice as much as the rest of the world. With the dramatic loss of ice cover in the Arctic, exposed ocean and land absorb more of the sun’s heat. The increased Arctic temperature destabilizes the Arctic jet stream – the polar vortex – and causes it to wander south with sub-zero temperatures.

Scientists say the meandering polar vortex is a natural phenomenon, but we can expect to see it happen much more often thanks to global warming.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) responded with a tweet of its own, stating, “Winter storms don’t prove that global warming isn’t happening.” It included a link explaining how warmer ocean temperatures contribute to bigger winter snowstorms, climate.gov/news-features/climate-qa/are-record-snowstorms-proof-global-warming-isn%E2%80%99t-happening.