Commentary: Be Cautious on Lake Michigan during Swimming Season

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

Lake Michigan is beautiful, but is considered by far the deadliest of the Great Lakes. It is responsible for more than double the drownings and rescues of the other four Great Lakes combined. The 307-mile length of Lake Michigan has long and uninterrupted east and west shores that can feature rapid river-like currents, and also strong rip currents, whipped up by wind and waves.

As the 2016 swimming season gets under way, caution is advised. In 1955 I saw firsthand how dangerous Lake Michigan can be.

Dad was anxious because he needed to leave for work, but his car had been parked in. Here he was, detained at Grandma’s cottage at Whitefish Dunes. Suddenly, above the loud roar of wind and waves coming from Lake Michigan, we heard a man yelling. He was approaching our place, “Please, could someone help?!”

Turns out his daughter, Doris, had ventured too far out while swimming in the large waves, and the current had dragged her into deep water. This nightmare scenario was happening in the north corner of Whitefish Bay. The river-like current was flowing outward along a deep underwater rock ledge. Today Whitefish Dunes State Park staff doesn’t allow swimming in that area due to the danger.

Her family could only watch helplessly from shore as Doris struggled against the overwhelming waves and current. At 20 years old, she was an expert swimmer, but quickly became exhausted from fighting the powerful current drawing her ever outward.

As huge waves washed over her, she would disappear for what seemed a very long time. She was wearing a tight fitting white swimming cap. We could see that small white sphere slowly rise back to the surface. She kept trying to swim back to shore right into the strong rip current, only to have another wave overtake her.

Unless a miracle happened quickly, it was only a question of time before she could no longer hold out. Then someone remembered an old wooden rowboat upside down on sawhorses in the yard at the cottage next door. A few guys ran to the boat. Unfortunately it was chained to a tree, and was secured with one of those large railroad locks. There was nobody home to unlock the boat.

My Dad, who should have been gone to work at Chicago Northwestern Railroad, happened to have the key that opened this lock in his pocket. That tiny ancient boat was then quickly hauled down to the shore. Now they just needed someone willing to take the rickety rowboat out into surging surf, despite the very real likelihood of sharing Doris’s impending fate.

As a seven-year-old (back in 1955), I still clearly remember my Dad stepping into that little boat and rowing out toward the intermittently visible and exhausted swimmer. As if by magic, he went right between the white breakers, over the dark parts of the waves. My uncle, Bob, directed him from the shore.

Having grown up on a farm in arid central Washington state, Dad was, at best, a novice rower and knew very little about waves or rip currents. When he got to where Doris was struggling, his boat turned and stopped. In the worst possible circumstances, it went right where it needed to be. He simply leaned over, grabbed her arms, and lifted her into the boat. Years later he described her as almost weightless, and he said that it seemed as if someone else was rowing the boat.

As Dad brought Doris back over the rocks into shallow water, the boat, which had been taking on water the entire time, actually sank. But now people were there to help them ashore.

Doris was cared for until she was fit to travel. She was then taken to a doctor in Sturgeon Bay, where she was treated and mostly recovered from this near-death experience.

My father, having done his part, simply left for work. Eventually the wind died down and Lake Michigan took on a more sedate demeanor. We were left to ponder what might have been.

A few days later, Dad received a letter from Doris’s mother, Dorothy. Here’s a small excerpt: “Doris was being swept out farther and farther and I was so helpless. Do you know, I had always thought that whenever any of the children would need my help, I would be right there to help them. Like when they are sick, one can do something for them, at least comfort them. But here I was completely helpless.

“She was out there all alone. When I saw that boat in the water it was such a ray of hope and when I saw that flash of red bathing suit in the boat, I didn’t see how it all happened, it seemed I went numb all over. Doris told us on the way home, that when you grabbed her arm it was the most wonderful feeling she ever experienced. She said she couldn’t have held out another minute. We still can’t talk about it to anyone. The last thing at night and the first thing each morning, there is just one song going thru our hearts. God has been so good to us and Ted Goodner was his angel. You were at that spot, with that key in your pocket, and a heart as big as Lake Michigan itself.”

For many years, Doris’s father delivered a beautiful Christmas tree to our home each December, as a fitting symbolic token of his appreciation. The green Christmas tree, of course, symbolizes the tenacity of life, during the darkest of times.

The public TV icon Mr. Rogers once said that when something awful or scary happens, look for the helpers. My father was a perfect example. A World War II veteran, he embodied the American ideals personified by The Greatest Generation: commitment, courage and capability.

For example, he often stopped the car to assist those in need, whether they were stuck in snow, or just stopped at the roadside. Perhaps his most important trait, for us kids, was dependability. You knew you could count on him. Turns out Doris was very fortunate that, when it mattered most, her father had indeed found a helper.

The current that had overwhelmed Doris was not a typical “rip current.” A strong southeast wind had caused a river of water to push to the north end of Whitefish Bay and then parallel the rocks outward and northward toward Cave Point.

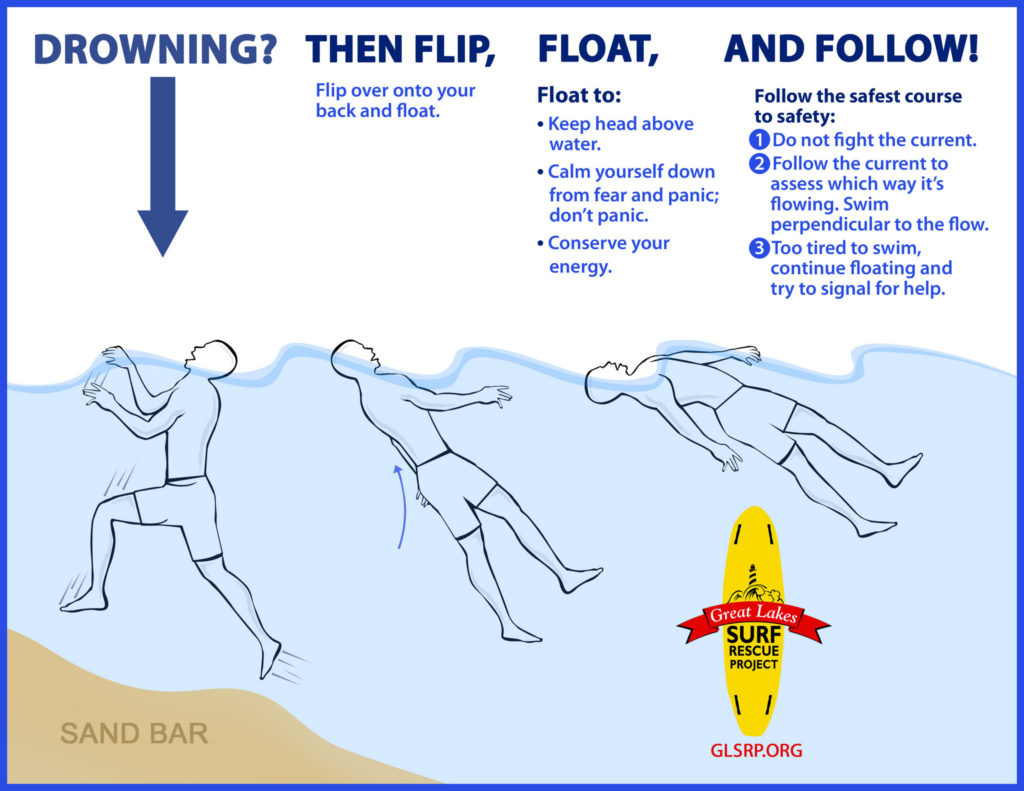

The most dangerous currents at swimming beaches, rip currents, result when water is pushed in over a sandbar by breaking waves. The accumulating water flows back outward several feet per second, through small gaps, at widely spaced intervals, through the sandbar. This current is tens of feet wide, and dissipates in deeper water, beyond the sandbar.

If you find yourself caught in a rip current, don’t panic, and don’t attempt to swim back to shore. The current will win every time. Your best bet is to swim parallel to the shore, or just float along with it. The rip current is relatively narrow and will disperse beyond the sandbar. Once out of the current, waves will aid you in swimming back to shore. If a lifeguard is on duty, you can hold up your hand for a rescue.

As kids we were often warned about the undertow, but that’s something else. When waves wash up on shore, the water simply washes back into the lake. This is called “backwash.” When backwash is substantial it’s known as “undertow,” and can pull you into the next oncoming waves right along the shore. When waves become very large, this can be life threatening, particularly for small children.

As kids we were often warned about the undertow, but that’s something else. When waves wash up on shore, the water simply washes back into the lake. This is called “backwash.” When backwash is substantial it’s known as “undertow,” and can pull you into the next oncoming waves right along the shore. When waves become very large, this can be life threatening, particularly for small children.

For more information, Google “rip current Lake Michigan.” There are several excellent sites that provide information, photos and videos on the dangers of rip currents.

How to break the grip from the rip:

- First, don’t panic.

- Float with the current in a horizontal swimming position so you can conserve energy until the current weakens.

- Swim parallel to the shore until the current no longer is felt.

- Swim back to shore.

Additionally:

- Do not jump off or swim along piers or other structures that build out into the lake.

- Structural currents are forced along the side of the pier, sweeping swimmers out to deeper waters.

Source: National Weather Service