Devotion to Duty: Norman Carol, WWII submariner, recalls life in the Pacific

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

Beneath the surface of the Pacific Ocean, torpedo man Norman Carroll manned his station on the USS Guitarro as the Gato-class submarine patrolled the waters to the west of the Philippine Islands.

The year was 1944, the tide turning in the Second World War, and on its patrol the Guitarro would pass near the Japanese-occupied island of Luzon, home to some of the war’s most vicious fighting, on its way to the South China Sea. Some 260,000 Japanese troops were stationed on the island, and somewhere in Japanese prisoner of war camps in the Philippines, Norman hoped his brother William was alive.

William was in the army, stationed in the Philippines when Pearl Harbor was attacked. The Japanese invaded the Philippines early in 1942, and the Americans stationed there had little chance. William got a message from headquarters. “Destroy your equipment, disband, and fight it out for yourselves,” Norman recalls. William obeyed and was declared missing in action.

Like so many of his era, Norman carried on not knowing the fate of a family member. On home soil, fathers continued to work, mothers kept families together, and wives somehow carried on in uncertainty. Norman joined the Navy and spent his days with 80 crewmates bathed in the diesel and sweat-tinged aroma of a submarine.

In 1942, straight out of high school, he signed up and left his hometown of Philadelphia for Great Lakes Naval boot camp. He became part of the crew for the Guitarro, one of 28 WWII submarines built in Manitowoc. When they were stopped at the Midway Atoll in the Pacific Ocean preparing for their first war patrol, they tied up alongside the Golet, a sub whose crew shared a warning.

“It’s really hell out there,” they told him. “Be careful.”

“We didn’t know enough, we were all just green kids,” Norman says. “Then the Golet was sunk on its very next patrol. We were pretty lucky I guess.”

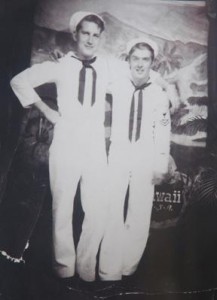

Norman Carroll pictured in his Navy days, at left. The photo is currently on display as part of Draeb Jewelry’s window display.

He would end up on patrol in Lombok Strait and Makassar Strait, but officers called them something else. “To us Lombok was Suicide Channel, and Makassar was Torpedo Junction. Those were dangerous places to go.”

In the decisive Battle of Leyte Gulf, Norman and his crewmates spotted the Japanese Central Force and tracked the ships through Mindoro Strait, providing vital information to help dismantle the Japanese Pacific fleet. For his “alertness and conscientious devotion to duty,” Norman was awarded a Navy Letter of Commendation with Ribbon.

They would not serve without their own close calls, and the pounding of depth charges (anti-submarine weapons meant to disable subs with the shock of exploding near a sub) became routine. Norman said a friend best described a depth charge by comparing it to “a giant standing on top of the sub with a huge sledgehammer, walloping the sub with blows.”

“We were supposed to keep count,” Norman says with a slight chuckle, “but after 400 we stopped. We figured there wasn’t any point, and nobody would believe us anyway.”

Living History

Sitting in his modest Sister Bay home, his old bowling mementos over his shoulder, Norman shared his stories. His wife Lenore played bingo at a small kitchen table, with Herb Alpert playing in the background on an old radio. The memories were so far away, it seemed, that even the voice of the man who experienced it all carried a hint of disbelief.

Sixty-five years have passed since the war that defined the perspective of his generation ended. The black and white pictures of the war and grainy footage are literally of another century, and its stories are now the subject of special effects-driven Hollywood spectacles. As their numbers dwindle, the men and women who served and lived through those harrowing years hope to remind younger generations that what they consider entertainment was once their reality.

Norman is one of less than 2,000 submariners left from World War II. So many of them are in poor health that their organization, the United State Submarine Veterans of World War II, is closing.

“They didn’t want us to talk about the war for years after,” he says. “Now they want you to tell the world.”

For a year and a half he lived in the bowels of a submarine in treacherous waters far from home, going as long as six weeks without a shower. “When we would get to shore, the first thing we all did was fill up a tub and soak in it up to our noses,” he says.

When the war came to an end, he re-enlisted for two years, then returned to Wisconsin, where jobs were scarce.

“I spent a year up here, and the shipyards were even shut down,” he says. “You couldn’t buy a job. That’s when I started picking stones, shoveling manure. All these farmers needed help with all the crap jobs. You’d work for 75 cents an hour. But the nice thing about working for farmers is they also fed you.”

He married, then returned to Philadelphia, working for a gas company, but returned a decade later to open a small restaurant, the Carroll House, in 1957. They ran the place for 25 years, working just a few steps from their home, where Lenore’s grandparents once lived – the one they still live in today.

They built a humble life, worked hard, kept their humor, the latter on display as Norman sprinkles jokes and self-deprecating anecdotes into his stories. Lenore interrupts her bingo game to join us for a moment, offering coffee to a scribbling writer and shuffling in a search for sweetener for me that she certainly doesn’t have to find.

As I take a sip, Norman’s mind drifts back to a country, and a family, at war. To a time when a postman came to his mother’s door with a special delivery. It had been three and a half years since she last heard from her son William.

“The postman knew my mom really well, and he knew what the situation was,” Norman remembers. “He had this letter from William T. Carroll, so instead of just putting it in the slot, he rang the bell. My mother came and asked what he wanted.”

“I have a letter for you,” the postman told her. “But I think when I give you this letter you should be sitting down. It’s from your boy.”

“You mean Norman,” she said.

“No,” the postman told her, “it’s from William.”

Her son was alive. William had hidden in the Philippine jungle for three and a half years with Philippine Guerillas, Norman says. When the letter arrived, Norman was still at sea, and his mother’s fears now turned to her other son.

“We heard from Bill after three and a half years, but we haven’t heard from Norman in over three months,” she said to William Sr., Norman’s father, a former Navy man himself, who gave a practical response.

“Well, at least we heard from one of them,” he told his worried wife.

After the war, the brothers compared notes from their service, and Norman mentioned the patrol that took him past the island of Luzon.

“Luzon?” his brother said. “That’s where I was hiding out. You could probably see the mountain I was on.”

Two brothers from Philadelphia, passing maybe 20 miles apart, separated by much more than distance.