Editor’s Note: Leaders Aren’t Leading When They Avoid Difficult Conversations

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

It’s pretty easy for us to be kind, gracious and open when the world is smiling at us and we don’t feel threatened by any person, place or thing. Who can’t do that; there’s nothing to it.

Add a little adversity, and things get interesting. This can be as small as a complaint or a snide remark; this can be as big as a tornado levels your home or you’ve lost your job and can’t pay your rent.

When the ground beneath our feet becomes shaky, when we’re looking out at a crowded room to speak on behalf of the too-often afraid and voiceless, and most of the eyes in the room won’t meet ours – that’s where we learn what’s inside us, what we’re made of, what kind of character we’ve built for ourselves.

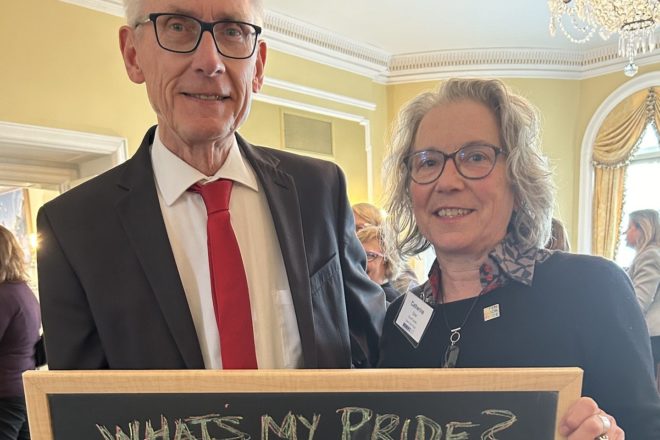

That’s why I was so impressed Tuesday with Cathy Grier and a response I received from her in answer to a question following her failed attempt to get the Door County Board of Supervisors to consider a proclamation in May for June Pride Month.

Many of you know the Sturgeon Bay resident as a musician; others as the founder and chair of Open Door Pride. She was speaking Tuesday as an advocate of the latter and as a member of a community our society has forced to identify as an acronym: LGBTQIA+.

“I don’t want to be an acronym,” she said, addressing the supervisors during their April 23 meeting, standing behind the podium at the front of the room. “We will keep using it until we can just be h-u-m-a-n.”

She asked them to put the proclamation up for discussion on their May agenda. The board said ‘no,’ with a 10-8 vote (see my story on this in this week’s issue).

The county adopted, by resolution, “Door County’s Vision of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion.” A year into the global pandemic and nine months since the first Black Lives Matter protests erupted in communities across the country, including in Door County, racism as a public health crisis drove that resolution’s birth back in April 2021.

But the final document didn’t stop at racism as a public health crisis, it acknowledged the many ways in which equity and inclusion are not achieved in society, including for “many groups of people based on identity factors such as age, disability, gender, gender identity and expression, race, nationality, ethnicity, parental status, religion, socioeconomic status and sexual orientation.”

The resolution also bound the supervisors to “support policies that improve access and remove gaps along social and economic constructs and advance the understanding of diversity, equity and inclusion.”

The resolution encouraged the advocacy of issues that “dismantle barriers and promote diversity, equity and inclusion” – and said supervisors were “responsible for creating and maintaining a culture in which we respect diversity, equity, and inclusion in the workforce and the community they serve.”

This resolution does not require the supervisors to adopt any and all proclamations that come their way. This resolution does require them, in my opinion, to at least discuss proclamations that are clearly of the “diversity, equity and inclusion” variety, and that come their way with the intention of promoting a more welcoming and inclusive community; that come their way with the intention of eliminating some of the “persistent disparities in health outcomes” brought about by “social, economic, educational and environmental inequities – language also in the resolution.

When I reached out to Grier for a comment, it was following the vote that killed the possibility of the discussion, effectively shutting her and her community down. Yet her answer contained the kindness, grace and openness she did not herself receive.

“We’re grateful that we have some movement forward,” she said. “That there are elected officials who want to see such a thing come forward is a great achievement. Civil rights never enter society elegantly.”