Feature: Reconciling with a Violent Klansman

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

James Chaney. Andrew Goodman. Michael “Mickey” Schwerner.

Those are the names of three young civil rights workers who were murdered by members of the Ku Klux Klan in Mississippi the summer of 1964, also known as Freedom Summer.

“Three more damn idiots that should have kept their nose out of Mississippi business and Mississippi politics and should have stayed at home. And they got what they deserved,” says Byron “Delay” de la Beckwith Jr. in the amazing 2012 documentary The Last White Night by Paul Saltzman.

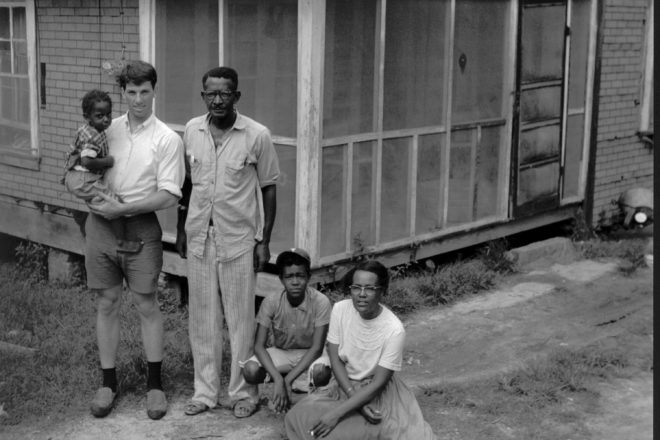

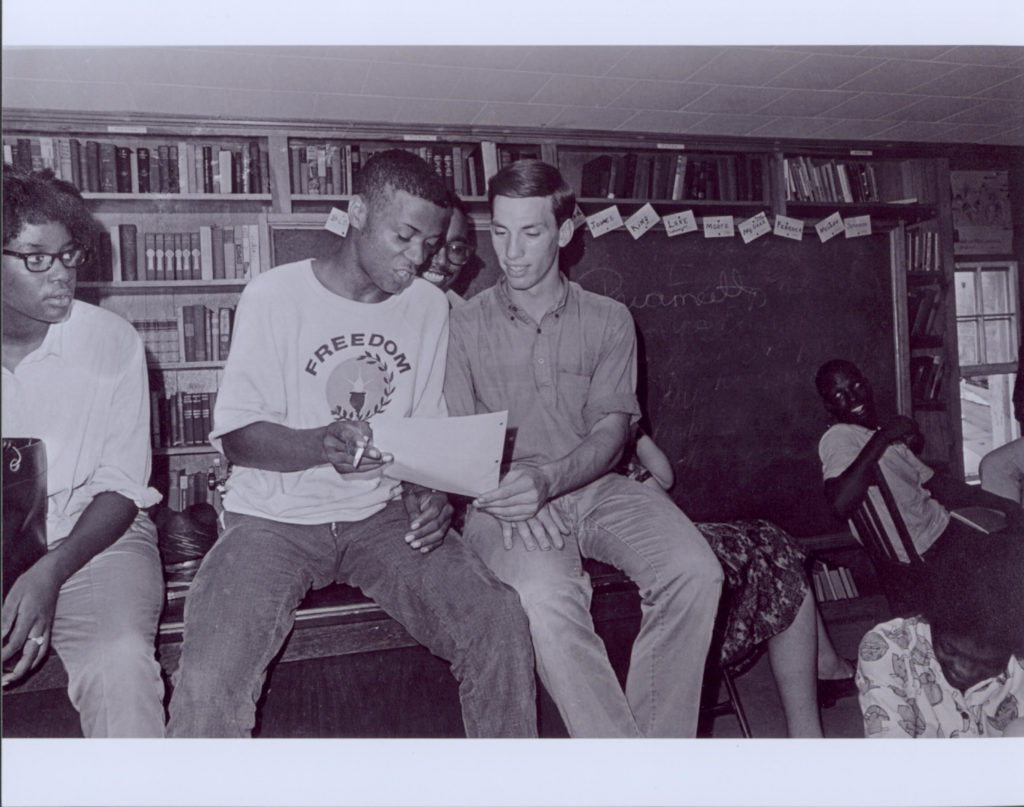

Saltzman was a young Canadian who was so outraged by American racism that he decided to go to the heart of darkness – the state of Mississippi – as a member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, a civil-rights organization that dispatched mostly Northern, white college students to Mississippi to register blacks to vote and organize community centers and other activities that drew the attention of the Klan.

“It comes from my essential belief system that we’re all children of God,” Saltzman said in a recent interview with the Pulse. “I read Mahatma Gandhi when I was 16 years old, and that was life-changing for me. My parents, who were atheists – no God, no soul, no spirit – still taught me the golden rule is the way to live: do unto others as you would have them do unto you. That was paramount in why I went to Mississippi in the first place to do civil-rights work.”

Saltzman was 21 when he went to Greenwood, Miss., the summer of 1965. In an animated segment of The Last White Knight, he tells the story of encountering the 19-year-old Beckwith and some of his friends. The encounter resulted in Beckwith punching Saltzman in the head.

“I was fortunate that, being an athlete, I could get away from him and his three friends,” Saltzman said.

Beckwith is the son of Byron de la Beckwith Sr., who died in prison in 2001 while serving a life sentence that was imposed in 1994 for the 1963 murder of civil-rights activist Medgar Evers.

Saltzman eventually returned to Canada and began a filmmaking career, with 314 film and television credits and two Canadian Emmys earned so far. That Mississippi summer and the assault by a young Klansman just became part of his history.

But it all came back with the 1998 unsealing of the records of the Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission, a secret police organization formed in 1956 by the governor of Mississippi as a reaction to the 1954 Brown vs. Board of Education Supreme Court ruling in favor of integrated public schools.

“Its sole purpose was to preserve the old south and keep blacks from voting,” Saltzman said.

When the commission was shut down in 1977, some Mississippi legislators wanted to burn the agency’s archives, but instead the documents were to be sealed for 50 years, until 2027. In 1989, the ACLU won its federal case requesting the unsealing of the documents, but legal challenges prevented the records from being revealed until 1998.

Once unsealed, it was found that the agency had collected 87,000 names – or suspects – in its 21 years of operation. The names included the murdered civil-rights activists Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner. Paul Saltzman was also included in the documents.

Shortly after, in 2000, Saltzman got a phone call from a newspaper reporter in Jackson, Mississippi, who had found Saltzman’s name in the unsealed documents.

“He interviewed me, and we talked a number of times. That rekindled my curiosity,” Saltzman said. “After a while, I started to think, whatever happened to Delay de la Beckwith?”

That thought sparked him to call the Mississippi reporter in 2007 to ask whether he knew Beckwith. The reporter did know him and provided Saltzman with the telephone number of the man who had assaulted him 42 years before.

“I called up Delay and said, ‘This is Paul Saltzman. You may not remember, but I’m the guy who you struck in the head in 1965, and I took you to court.’ He said, ‘Oh, I remember you. I always wondered what happened to you.’ I don’t know if that was genuine or Southern bonhomie, but that’s what he said.”

That was the start of a five-year relationship that resulted in The Last White Knight, which has as its subtitle Is Reconciliation Possible?

“In a way, we had no issue getting along from the first conversation,” Saltzman said. “We talked for a couple of hours. We talked a number of times.”

During one of those conversations, Saltzman said he would like to interview Beckwith in Mississippi, and Beckwith agreed to the idea.

“I wanted to meet with him, to see if reconciliation is possible. Can we talk to each other without violence?” Saltzman said. “Not to convince. There was never a moment that I was trying to change him or convince him or be better than him or be right. I think that was key to why he opened up, probably more than he ever has.”

Saltzman – who has said, “One of my strongest yearnings in life is to be authentic and to be real and to be heartful” – already knew how the meeting should begin.

“I said to him, ‘I don’t want to meet you before we have cameras running.’ I wanted an authentic meeting where we first met,” he said.

So they picked a day and time to meet in front of the courthouse where Beckwith had attacked Saltzman.

“When he came walking down the sidewalk, that was all in real time. I had two cameras rolling when he walked up to me so it could be authentic and real.”

They also did an interview at Beckwith’s house, and in Buffalo, N.Y., and in Memphis.

You learn in the film that Beckwith is an unrepentant racist, and also that he is not alone.

“You take it ’til the day you die,” Beckwith says about being a Klan member. “I would say I am an ordained Klansman until my death.”

But in one of the spookiest moments of the documentary, Saltzman interviews three gaudily dressed and hooded current members of the Mississippi White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan about their beliefs.

“It’s not hatred – just pride in our own race,” says Richard Green, the 45-year-old imperial wizard of the organization. “That’s how I was brought up, and that’s how it remains today.”

Saltzman asks, “Were you taught that black people were inferior?”

“I don’t really see any civilization ran by black people that’s ever accomplished anything, so yes, I would have to say that, uh, whites are the superior race. I believe they were created to be servants.”

Saltzman gets Beckwith to talk about their first meeting.

“I popped you,” Beckwith says.

“I remember I was much faster than you,” Saltzman says. “Thank God, eh?”

He then asks his assaulter what would have happened if he and his friends had caught up with him.

“I imagine you would have been sore for two or three days,” Beckwith answers with a smile on his face.

What did Saltzman gain by reconnecting with his attacker, other than a fascinating documentary?

“I’ve been asked many times, how could you just sit there and not be enraged?” he said. “The fact is, I was never feeling judgmental. That rage comes from judgment. I was just interested in saying, who are you today? Who were you then? Can we talk to each other without violence?”

To do this, Saltzman decided he would talk to Beckwith alone in a room, just the two of them, without another person working sound or cameras. It leads to fascinating exchanges, including what Saltzman said for him is the “single most thrilling moment”: when Beckwith goes on a rant about Jews causing all the problems in the world.

“I didn’t know he was going to say that. It was a true conversation,” Saltzman said.

So he says to Beckwith, “Well, you know I’m Jewish?”

He goes on to refute Beckwith’s assertion that Jews run the media and major corporations with real statistics showing they do not.

“The next moment I think is the most revealing moment in the film,” Saltzman said. “The camera is on him. You can see the smugness drop and is gone. In that moment he says, ‘Maybe I wasn’t brought up right.’ How many human beings acknowledge that?”

So, did that mean the process of making the film changed Beckwith?

“Yes, for sure – and not so much,” Saltzman said. “What I mean by that is, we became friends. There are many forms of friendship. We don’t call each other or see each other, but if there’s a reason, he’ll call or I’ll call. But we’re friendly in the sense that I accept who I am, and he accepts who I am. As I said at the end of the film, I know who you are, and you know who I am.

“I think he did change,” Saltzman continued. “Even that he considers me a friend as a Jew is a change from the 19-year-old who punched me in the head and hated Jews. So, yes, I think there was a big change.”

1968 Ashram Visit Led to Many Projects

In 1968, Paul Saltzman traveled to India to study mediation at Maharishi Mahesh Yogi’s ashram. He was there at the same time as The Beatles, Donovan, Mia Farrow and Mike Love of The Beach Boys, all of whom allowed Saltzman to photograph them. Not only did the experience change his life, but it also led to a variety of projects.

The photos he took of The Beatles resulted in a book published by Viking Penguin in 2000, The Beatles in Rishikesh. In 2006 he released a limited-edition box set of The Beatles in India, and he is currently working on a documentary called Meeting the Beatles in India.

Since that first visit to India, Saltzman has made more than 60 trips back.

With the 2000 book release, he was invited to exhibit his photos from the ashram in various galleries around the world.

“Something very curious happened,” he said. “People would come up to me and always say the same thing, ‘I’ve always wanted to go to India, but it scares me.’”

He would then ask what scares them, and the answers would be the poverty or how crowded it is.

“India is not crowded at all,” he said. “It’s 80 percent agrarian culture, so most of India is farmland, huge open spaces. You get to the large cities, it’s no different than Manhattan.”

That led him to what he describes as his hobby: hosting small-group tours to India. He has taken several tours there with a total of 64 people. The next one – his fifth – is scheduled for 2020.

“I do that out of love as well,” he said. “I make some money at it, but for the amount of work it takes, the money is fairly unimpressive.”

For more information, visit bestway.com/tours/pvt/paul-india.