Harvey Haen, Much More Than Egg Harbor’s Mr. Fix-it

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

In the days when tourism was only a sidelight in Egg Harbor, when the community was a workingman’s town of cherry pickers, farmers and shipyard workers, nobody was more necessary – or more admired – than the man they called Mr. Fix-it.

“If it ran, floated, or towed, Harv could fix it,” Art Witalison wrote of Harvey Haen in a letter recognizing Haen’s 90th birthday in 2002. If you bring up his name to anyone who has lived in the town for more than 30 years, they’ll say the same.

Harvey Haen was the sixth of 13 children born in 1913 to Joseph and Theresa Haen and raised on a farm on what is now County Road E outside Egg Harbor. He learned to fix machinery at the side of his father and for the rest of his days, he tinkered with his hands and his mind. Around age 20 he built his father a tractor to plow his fields, and long before it was common for farmers to own them, Harvey built 11 tractors from Model T, Model A, and Chrysler cars.

In 1933 he met Helen Martens, the perfect partner for a man who never wanted much more than a problem to solve, a good conversation, something to learn, and meals at 7:00 am, noon, and 5:00 pm. In 1942 they bought the Sinclair gas station in the center of Egg Harbor, right as Highway 42 bends toward the Cupola House heading north, and named it Harbor Service. Harvey worked days at Leathem Smith Shipyard, so Helen pumped gas from the two pumps out front, washed windows, checked oil, did the books, and scheduled Harvey’s repair jobs for the evenings, when he would come home and work until 10:00 or 12:00 at night.

“She put up with all the male crap,” remembered Dan Haen, one of their five children, “And she had a way of calming Harvey when he would get excited about something. ‘Oh Harvey, say a prayer,’ she’d say.”

One of her great tasks was trying to get him to charge people for his work. “His conscience would hit him,” Dan said. “He’d put down eight hours on a job, but then later he’d go back and change it to six or four because he’d say that the guy couldn’t afford that much.”

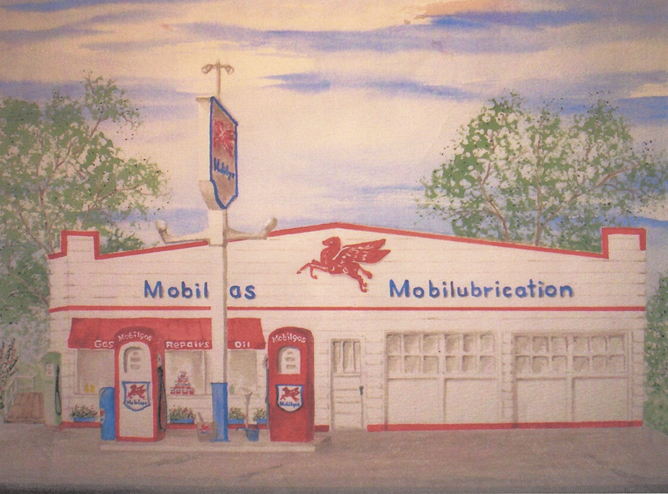

In 1947 they switched to Mobil gas when Harvey’s brother Lawrence started working for the company, and by then the station had become more than a repair shop – it became a gathering place in Egg Harbor.

When travelers were waiting for the bus out front on a cold day, Helen invited them inside to stay warm. When bored kids wandered into the store, Helen and Harvey let them linger in the waiting room admiring the pop machine and probing Harvey with questions. Harvey was happy to oblige with stories, and not just for the kids.

Jim Petersen said Helen always had coffee on and bakery ready in the days when there weren’t a lot of places to grab a cup in Egg Harbor. But you never heard the radio. Harvey couldn’t work with the radio on.

“You have to keep your mind clear,” he said in an interview recorded when he was 89. Instead of the background sound of the radio, Harvey talked…and talked.

“You’d stop by and Harvey would say, ‘Well, as long as you’re here, you might as well stick around and have a cup.’ And you would,” Petersen said. “They were such outgoing people. You’d talk to them two or three minutes and you knew them all your life.”

“You never knew who was coming to lunch or dinner,” remembered his daughter Judi Dexheimer, who by age 10 was pumping gas and washing windows for her parents. “If you came by for repairs at noon, you were invited in for lunch. If you brought your car by in the evening, he’d invite you in for supper. If you came later, we might be having a second supper.”

Fortunately Woldt’s grocery store was next door, and the kids could easily be dispatched to fetch a little more food for the guest.

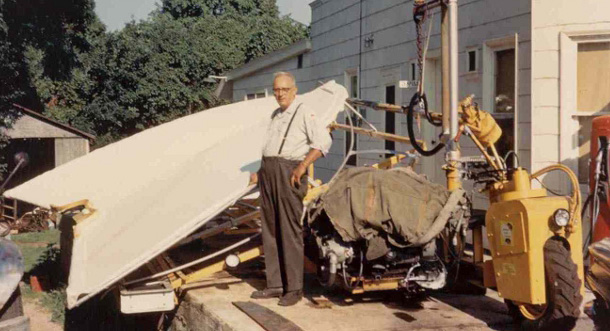

When Harvey didn’t have a part, he didn’t always order it, he often fashioned it in the shop. He knew the intricacies of welding and returned to vocational school as an adult to learn about hydraulics, quickly becoming an expert and incorporating it into his creations, which were more functional than eye-catching.

But Harvey didn’t just repair things. He improved them, built them, invented them. He built 11 tractors back before they were common. He made go-karts and pedal karts for his kids that were the wonder of Egg Harbor boys for generations. He invented a cherry shaker that was once the dominant form used by orchards throughout the peninsula.

Harvey Haen’s garage was not a picture of meticulous organization. Dan learned the trade from Harvey, but they often struggled to work together. Dan thrived on organization, Harvey on the organization in his mind. As hard as Dan worked to keep it clean and in order, Harvey seemed to work just as hard to create a beautiful mess only he could understand.

“I’d clean a work bench, and the next day there would be piles of junk on it,” Dan recalled. “He’d shove stuff underneath it, on it, everywhere.”

“It drove Dan crazy,” Judi said. “He was so neat, and Harvey couldn’t work without a mess.”

Harvey would survey a pile of junk behind the shop and see what nobody else could see. A shape would grab him, and pretty soon a useless piece of an old car or boat would be just the piece he needed to get a tractor back in the fields again, or to pull a Pontiac out of the lake.

“He was like an artist that way,” Dan said. “He could look at a big pile of junk and see a shape he needed.”

Many considered Harvey to have one of the most fascinating minds they’d ever known.

“I’ve always felt that Door County is fortunate that Harvey Haen, with his inventive mind, decided to move here instead of to some big city where he probably would have become a noted engineer,” wrote John Enigl, a longtime journalist and historian in Egg Harbor.

Harvey Haen only had an eighth grade education, as high school wasn’t common for rural children in the 1920s. He loved to learn, and throughout his life he took classes to expand his knowledge, and was known to read encyclopedias to pass the time. He was never confident in his writing, so he turned to storytelling to pass on his knowledge, mastering the art form and earning a legion of friends. He served as fire chief for years, was elected the first Egg Harbor Village Board President, and was the first President of the Egg Harbor Men’s Club.

In 1979, after 37 years pumping gas, giving directions, and feeding strangers at their kitchen table, Harvey and Helen sold the gas station and moved into the house down the street, but Harvey wasn’t the retiring type. He tinkered out of his basement, doing repairs and inventing machines on the dirt floor, yelling up to Helen to unplug the dryer when he needed to fire up the welder.

“He just couldn’t quit working,” Dan said. After Helen died in 1998, Harvey moved into an apartment complex in Sturgeon Bay, where he promptly set about tinkering. The day after moving in he had bolted his recliner to the floor to keep it from sliding and created a lampshade for the kitchen table to direct the light precisely where he wanted it. His children figured that by the time Harvey was done, they’d end up having to buy the place.

Harvey died in 2004, age 91. The gas station where the town brought their broken down tractors, cars, lawn mowers, and anything with a motor is long gone. The place where many a cup of coffee and impromptu meal were had at the Haens table now only a memory. But in this case, the march of progress may have gotten something just right.

Harvey and Helen’s homes welcomed everyone in town for more than 50 years – a weary traveler, a local tradesman, the neighbor’s kids. The shop and their home were bought and torn down to expand Harbor View Park, where today everyone is welcome to gather day and night, just as they did at Harvey and Helen’s for decades.

When Harvey died, one family member wondered “what he might have become if he had the opportunity of a higher education.”

To the people of Egg Harbor, he couldn’t have been much more.