Re-Presenting: The Works of Bruce Basch

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

Bruce Basch is one of those rare artists who doesn’t measure his success by the number of works he sells, but rather by the success of new ideas, color nuances and kitschy provocations. Basch lives the kind of in-between life as an artist and waiter that affords the leisure of moving at whim – but always returns to Door County for the summers. His family owns land just on the north side of Ephraim and the site is an historic tract with a view you would take for granted if you lived here all year.

Basch’s weathered little studio sits in this picture perfect scenery like a remnant of life 100 years ago. The wood-frame building was originally built in Minnesota in the 1800s. It was taken apart board by board and pieced back together by Basch in 1970. The land has been in the family since 1865, and gracefully escapes the encroaching developments to the north and the south. The exterior of the studio is a simple wood-sided building, relatively unadorned but for the few collections of stones and pots at the doorstep and a little refrigerator “shrine” in the back which neatly displays a collection of disparate objects – a reflection on manmade versus natural creations.

Basch and I sat in his studio for several hours one night talking about everything in sight. The studio opens into a small entry with a steep ladder to the loft and collections of near-finished artworks fill the available spaces. Bookshelves line the walls and are filled partially with books, but little oddities catch the eye: a vintage fan painted blue, Jesus at the center; books wrapped, sealed shut with astrological charts and other objects riveted to their covers; cigar boxes; religious icons (mostly Mary); and a plethora of odds and ends with no business here in the woods – except that they are the bits that make up Basch’s artworks.

Basch began his long student life with printmaking, photography, and other elective studies at Saint Cloud State University in Minnesota, and experimented with various art forms, picking up what he found interesting. Prints from this time start to show themes that recur throughout Basch’s works, with borrowed imagery from graphic culture. In the early ‘70s he left printmaking with a “desire to work more spontaneously,” and began to paint and fill the gaps with mixed media collage, and ended his formal study by earning a Master of Fine Arts degree in painting from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 1994.

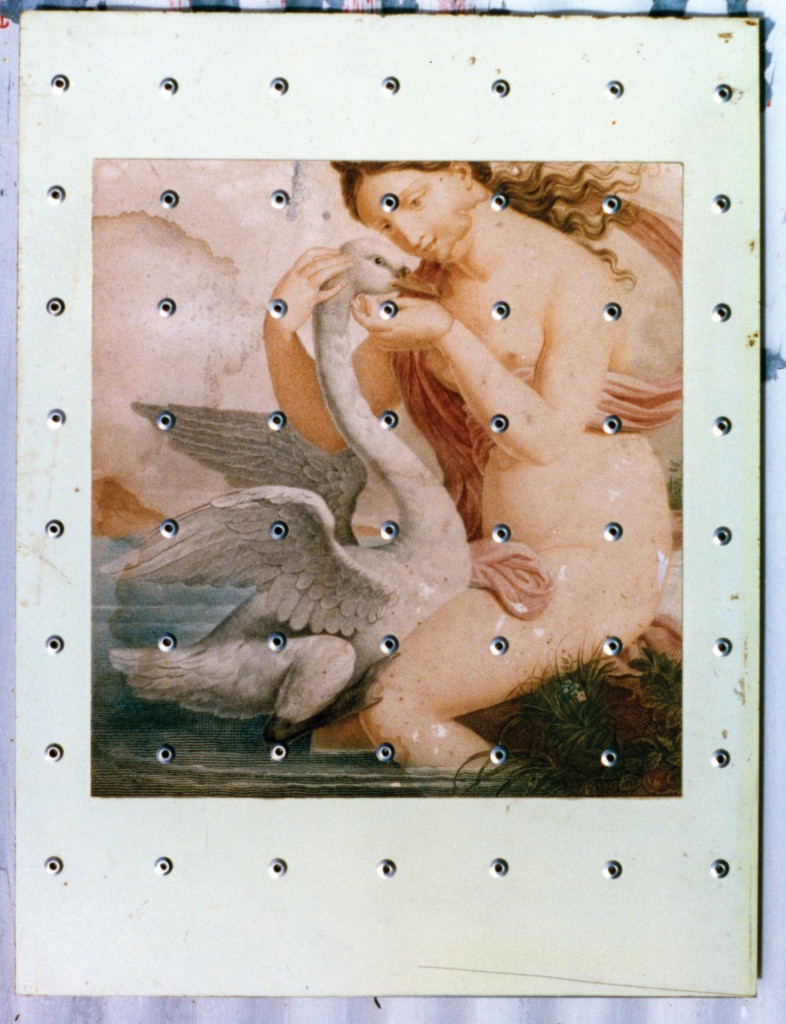

His works have evolved into an amalgamation of found objects, graphic lettering and borrowed imagery. Many of the objects he uses could already be considered everyday art: paint by numbers found in garage sales, floral print tablecloths and platters. Basch is “re-presenting or re-invigorating or re-purposing” junk art and kitsch, attempting to make high art from low, making no pretense that it is original in concept.

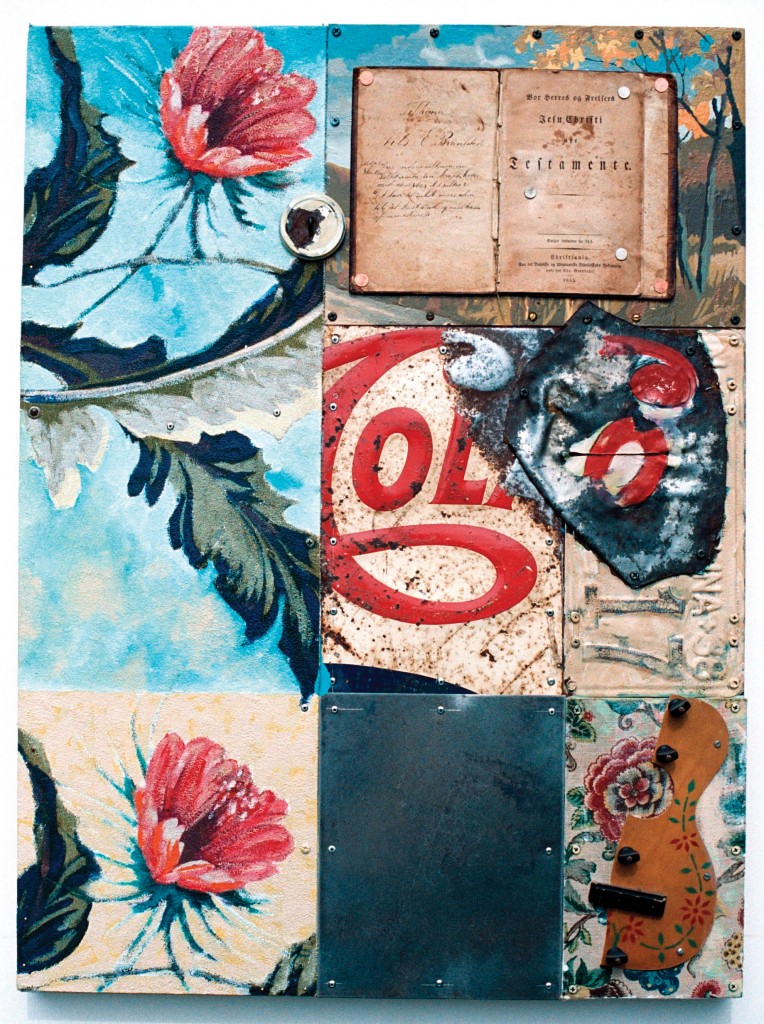

One painting that exemplifies this very theory hangs in Leroy’s Water Street Coffee. Like a Rauschenberg in bas-relief, the painting, Cola (Testament), is very alive with the textures of a floral tablecloth and a stamped metal cola sign. A book laid open to its cover page is squarely riveted into a pastoral paint by number and the face of a ukulele frames the center of a flower with its sound hole. A shiny but torn piece of metal flows over the surface in juxtaposition to an evenly rusted piece fastened neatly by rivets. Basch says, “I can’t really call this a painting. It’s a put-together of sorts…but I don’t even know what sort.”

And somehow the subtle chaos of colors all works together: a coral red in one flower brings out the crimson in the cola sign; the little yellow leaves of a paint by number tree are balanced by both the ukulele and in the opposite corner by a yellow field neatly painted around the floral pattern by Basch; and little flicks of sky blue show up throughout, even in the reflective aluminum. Basch’s color seems well thought-out, as if an interior designer should take cue. Basch said of earlier works, “I have had periods when I used a lot of color that was not overly successful. I can be gentle now.” There is a balance to the colors in his larger pieces that is truly gentle on the eye. No color seems bound to the canvas though. Over existing prints, Basch has imprinted more fitting colors, sometimes in layers that speak to the time spent on each individual work.

Cola (Testament) picks up on a number of other techniques Basch employs throughout his works. Without drawing overt attention, many of his pieces are divided into nine sections. Some are more obvious than others, but the subtlety speaks to a refinement of style over the years. Basch’s use of “the grid” as a transposing tool in painting evolved into an often-employed compositional principle. Basch says he’s always had a “penchant for dividing things,” a reference perhaps to his time divided between Naples, Forida and Door County or to some other distinction he makes in the episodes of his life.

Most of Basch’s works are not on the traditional canvas, but are creations bound over other ready-made forms, what he calls “hard-body” paintings. Using cigar boxes, books, and solid framed boards allows a little more flexibility when it comes to choosing what to rivet on next. His book works are some of the most intriguing of this sort. The concept itself is enough to make a person love them. “They are kind of object-like anyway, since most people don’t read them,” says Basch. And his reformations would be impossible to read in the traditional sense. They require a whole new kind of reading –?one in which you simply translate the cover. Basch’s careful covering leaves every nuance of the form intact; the divot formed next to the binding and the overhang of the cover can be no other object but a book. Luckily, books take well to the riveting procedure, and a few books in the studio were dolled up with vintage puzzle pieces and mixed religious imagery, atop the whitewashed coverings of illegible foreign words and charts.

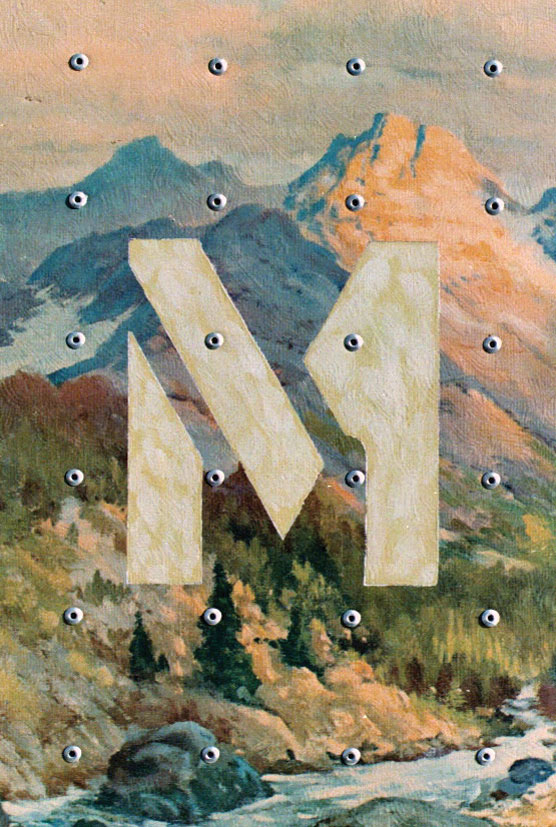

Books seem like a natural progression from the lettering in many other paintings. Basch inserts seemingly random letters into paintings that leave no sure footing as you tread around the meaning. One painting in the studio sports the letters MAR. Asked, Basch said maybe it was part Mars, or part March birthday, but clearly it was open for interpretation. Mar is a word itself, though its presence doesn’t detract from the painting whatsoever. In fact, it makes it more memorable. We are so accustomed to interpreting letters; in this context, however, words bring the paintings into another circle of understanding, without spelling out any single interpretation.

In many ways, Basch’s works appeal in a way that other art cannot. His pieces are timeless in their colors and style, and the constructs contain references that leave open-ended interpretation. This isn’t what drives Basch to produce his artworks at all, though. He says he will continue to “just do what I do, without worrying about the commercial viability of it.”

Basch’s works are currently on the walls of Leroy’s Water Street Coffee and The Spa at Sacred Grounds. Basch can be contacted through the fall at (920) 854-2610 or [email protected].