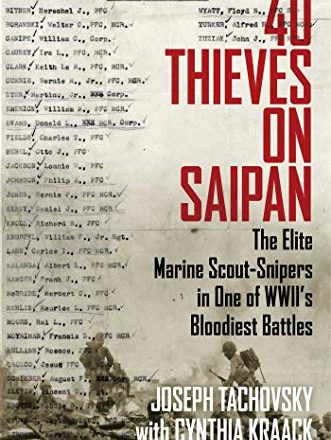

REVIEW: 40 Thieves on Saipan

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

During World War II, the mountainous Pacific island of Saipan was known as Japanese Emperor Hirohito’s “treasure”: the first of a chain of Japanese islands that led to Tokyo. The Japanese were prepared to defend Saipan to the last person.

The United States Marines decided to create and send an elite “scout-sniper platoon” as a spearhead to the invasion of Saipan. Its mission would be to wreak as much havoc as possible, especially behind the enemy’s front lines.

The man chosen to lead this platoon was Lieutenant Frank “Ski” Tachovsky, who had demonstrated extraordinary courage under fire. The commander of the invasion force was Gen. Holland “Howlin’ Mad” Smith.

Ski knew exactly what kind of Marine he needed for his platoon: men who could think on their feet and who were not overly impressed by rule books and officers. If a man had been punished for brawling, so much the better: “You’re not a good Marine until you’ve been thrown in the brig once or twice,” he said.

The ability to steal without getting caught would definitely come in handy behind enemy lines. One of the candidates bragged, “I’d steal anything that wasn’t nailed down, unless I needed the nails.”

The one thing Ski refused to tolerate, however, was bigotry.

“If you’re a bigot, you’re not a man,” he said. Applicants were told, “In the field … you’ll have somebody’s back, and they’ll have yours. If you’ve got a problem if that back is brown, red or white, then this outfit isn’t for you.” Any applicant who fidgeted at these words was summarily dismissed.

Ski’s son Joseph has recently recounted his father’s wartime experiences and exploits in 40 Thieves on Saipan. As one would expect, 40 Thieves depicts a platoon filled with rambunctious characters for whom booze was the water of life and stealing was an area of special expertise.

One morning, four of them decided to take advantage of their “liberty day” to go on a booze run to a nearby Army supply depot. To expedite matters, they stole a Jeep that had been left running – an Army captain’s Jeep, and thus fair game. A pair of wire cutters got them past the dangerous-looking barbed-wire fence that protected the depot, and one of the Marines was a talented locksmith who easily picked the lock on the largest building.

It turned out to be an Ali Baba’s cave of high-quality liquor. When the four returned to their battalion, they received a heroes’ welcome. Escapades of this sort soon earned Ski’s platoon the nickname “Forty Thieves.”

But not even a Marine can live on alcohol alone. After a period of intense training, Ski decided to reward his men by throwing a barbeque. He sent out a squad to hunt for dinner, but wild game proved elusive or absent altogether.

Rather than return empty-handed, the men jumped the fence around a conveniently located farm and stole a pig and some chickens – a caper that was strictly forbidden. The squeals of the pig alerted the farmer, and when he showed up at the feast, Ski paid him for his pig.

“The boys deserved a break,” he said. “Besides, it could be any day now.” (If anyone wants to prepare a seaside pig roast for 40 starved picnickers, read the instructions in Chapter 16.)

Indeed, very little surprised Ski. One of the Thieves attempted to pierce his own ear so he could wear a gold earring like the one Errol Flynn wore in his movies, but he succeeded only in nailing himself to a fence post.

On another occasion, three of Ski’s men were at the beach, busily unloading supplies, when the soldier in charge ordered them to stop their work to unload a piano for the officers’ club. After uttering a suitable amount of profanity, the trio grabbed the piano and threw it overboard into the sea.

“It slipped,” said one. “Oops,” remarked another.

The day of battle did indeed come, bringing with it scenes of horror that few civilians can imagine – scenes too horrific to describe in a civilian newspaper – and the book’s descriptions of battle and its aftermath leave nothing to the imagination.

Occasionally, however, a poignant moment comes, as when one of the Thieves examines the pack of a dead Japanese captain and finds photographs of the captain’s family. Seeing himself in the face of the captain, the Marine takes the captain’s sacred “good luck” flag and vows to return it to the man’s family when the war is over. At the age of 93, he was finally able to keep his promise.

Ultimately, the Americans secured Saipan, and the Japanese general in charge of Saipan died by suicide. Ski survived and returned to his wife in Wisconsin. They settled in Sturgeon Bay, where Ski was twice elected mayor and also served as postmaster. Because of persistent nightmares, however, he never again slept through the night and instead got his rest by taking catnaps.

Obviously, this is not a book for all readers, and it should definitely be kept away from children. But anyone who wants a warts-and-all depiction of life and heroism during times of war can read Forty Thieves with profit.

Carolyn Kane is a professor emerita of English at Culver-Stockton College in Canton, Missouri, who lives in Door County. She founded a popular writers’ conference for high school students and sponsored an award-winning collegiate magazine. Kane is also the author of Taking Jenny Home, which was named to Kirkus Reviews’ Best Books of 2014.