Behind the Scenes of the Door County Historical Museum’s Taxidermy Display

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

To many people (and I include myself here), the prospect of skinning a dead animal, filling it up with foam and stitching it back together would be unnerving, to say the least.

But that’s not at all the case for Mike Orthober, who owns Wildlife Wizardry Studio in Egg Harbor, is a 2019 inductee into the Taxidermy Hall of Fame and has populated the Door County Historical Museum’s Seasons of Life wildlife diorama with taxidermied rodents, reptiles and – his favorite – birds.

During a July 30 demonstration at the museum, Orthober prepared a pine grosbeak to add to what he called the “clumsy bird” collection, which earned its nickname because most of the birds on display had died after flying into windows and were then donated to the museum.

The results of Orthober’s work are beautiful – vibrant blue jays, majestic kestrels, hawks captured mid-swoop – but the process is not for the faint of heart.

The Taxidermy Process

Orthober’s demonstration began with skinning the bird “like you would skin a chicken from a grocery store,” he said. Most birds have a small, featherless strip running down their breast, so that’s where he made his incision.

After “unzipping” the grosbeak, Orthober removed its internal organs slowly and carefully to keep its shape intact. After he’d finished, he set the peeled bird aside, and it bled slightly onto a piece of paper next to his can of Coke.

Though that sight left me feeling slightly horrified, Orthober was unfazed, probably because he’s been mastering his craft for 49 years. At age 13, he used library books to teach himself how to taxidermy animals.

Orthober was originally drawn to the practice because he enjoyed taking things apart, putting them back together again and discovering their inner workings in the process.

“I see it as sort of a science project,” he said, but at many points in the process, it looked more like an art project.

Equal Parts Art and Science

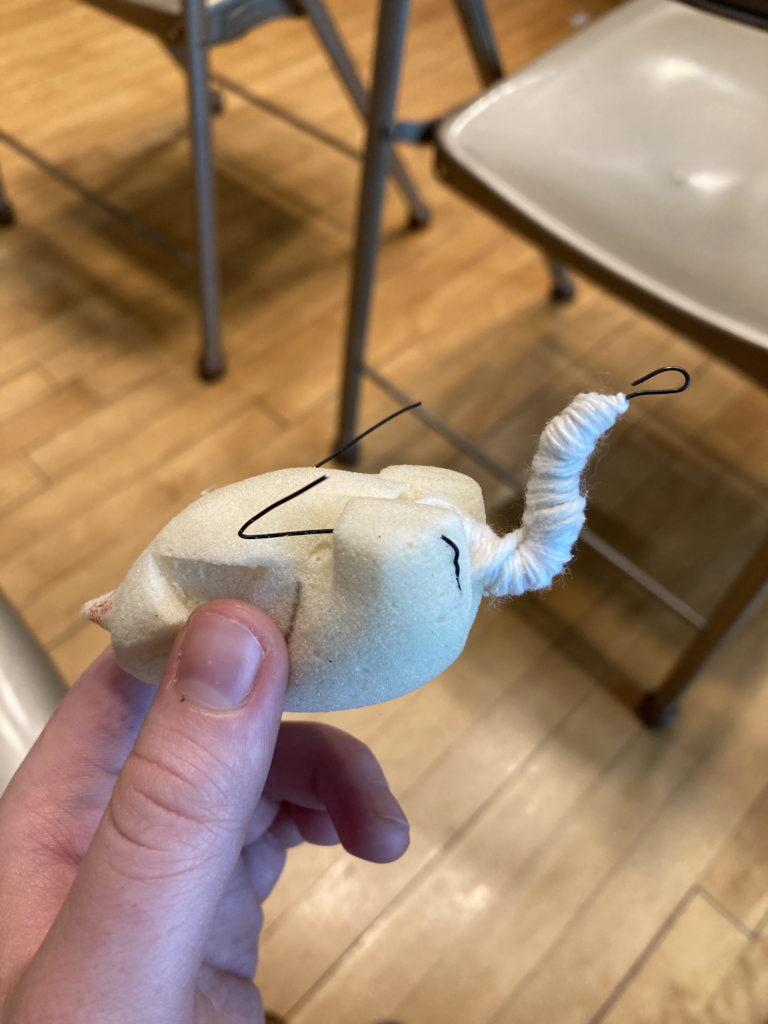

The artistic side of Orthober’s work emerged as he sculpted the model of the bird, using the chunk of meat and bones he’d removed from the grosbeak as a reference. He carefully whittled the bird’s shape out of a large piece of foam, adding wire where he planned to attach its wings and neck.

This wire allows birds to be posed and adjusted after being taxidermied, unlike mammals, which are posed beforehand. That’s one of the reasons why birds are Orthober’s favorite creatures to taxidermy.

Still, this particular bird presented some difficulties, forcing him to apply a layer of glue to its thin skin to prevent it from tearing. But he’s completed much more difficult projects, from a 500-pound black bear to two miniscule hummingbirds on display behind him.

According to Orthober, understanding how an animal’s body parts move and fit together is key to properly taxidermying any animal.

“If you don’t know the animal’s anatomy, it’s not going to turn out right,” he said. But that’s not a problem for him as he names the bird’s bones and slots joints out of foam so the grosbeak will be able to move realistically once he’s finished.

Though “Mr. Grosbeak,” as Orthober called his specimen, was giving him a hard time, it still usually takes him six to seven hours to complete a bird that size. During those hours, he shifts among roles as a sculptor, anatomist, engineer and artist.

And Orthober does it all so masterfully that I almost forgot he was operating on two halves of a bird – one of which looked like a floppy, feathery puppet and the other like a tiny, red rotisserie chicken. At certain points in the process, I couldn’t help but grimace – but I also couldn’t look away.

“Don’t worry,” he said jokingly when he saw my expression. “It doesn’t hurt him.”