A Surrealistic Journey at the Miller Art Museum

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

“I wish to instill suspicion in that which seems familiar.”

— 20th-century Belgian surrealist painter René Magritte

Surrealism became an official artistic movement with the publication of André Breton’s Surrealist Manifesto in 1924, but surrealism has always been around. It seems to be part of the human condition. Some suggest that surrealism has become the new reality of modern life.

Reading his manifesto today, Breton seems like a blowhard when he declared that “once and for all,” he would define surrealism. He felt he had that right because “there can be no doubt that this word had no currency before we came along.”

He goes on to recognize that surrealism has always been with us and snarkily names fellow writers with surrealist tendencies (meaning they were not full-time surrealists), from Alfred Jarry and Edgar Allen Poe to Jonathan Swift and Victor Hugo.

Surrealism can take many forms: advertising, art, architecture, cartoons, comedy, film, music, politics, religion, theater, writing, thinking, dreaming, inventions.

If 14th-century painter Hieronymus Bosch wasn’t a surrealist, nobody is. In fact, art seems to attract the greatest number of surrealists: Guiseppe Arcimboldo, Caspar David Friedrich, Arnold Böcklin, Francisco Goya, Vincent Van Gogh, Henri Rousseau, Georges Seurat, Claude Monet, Pablo Picasso, Franz Marc, Edvard Munch, Edward Hopper, M.C. Escher, Giorgio de Chirico, Grant Wood and Peter Max — to name just a very few.

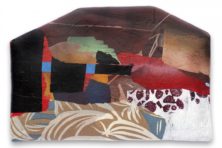

The movement’s influence has been widely felt, as one can see in the Miller Art Museum exhibit Extraordinary Things: Wisconsin Surrealism in the Permanent Collection.

The exhibit features 44 pieces from its permanent collection of 1,200 (and counting) works. The pieces range from avant garde to folksy, but all are provocative, as surrealism is meant to be. As Salvador Dalí said, “Surrealism is destructive, but it destroys only what it considers to be shackles limiting our vision.”

“Some of these works are a bit unusual for the community and what they know the Miller Art Museum as, so it’s a great opportunity to really see the depth of the collection,” said the Miller’s visionary executive director, Elizabeth Meissner-Gigstead.

Miller Art Museum Executive Director Elizabeth Meissner-Gigstead (left) and Curator Helen del Guidice take a tour of Extraordinary Things: Wisconsin Surrealism in the Permanent Collection. Photo by Len Villano.

This show also gave newly hired curator Helen del Guidice the opportunity to explore the collection of Wisconsin artists while choosing pieces for her first exhibition.

Del Guidice arrived at the Miller by way of New Orleans, San Diego and Rome, but she’s a Chicago native. Once she left the Midwest for warmer climes, she swore she’d never come back, but, she said, the opportunity the Miller offered seemed to be a perfect fit for her.

She relished the idea of a Wisconsin surrealism exhibit, which was a concept even before she joined the Miller.

“We have a really strong collection,” she said. “I was really impressed with the pieces in the collection that spoke of this.”

Del Guidice said the surrealist movement of the early 20th century went on to influence so many other things — some that might not be overtly surrealistic but instead “play with the toys of surrealism.”

She said John Wilde is an example of a classic surrealist. You see that in this exhibit with his “Feathers #7,” which is reminiscent of the work of René Magritte, the classic surrealist quoted at the beginning, who only wanted to “capture the mystery of the world.”

When looking at Wilde’s work — or that of any surrealist — we are “entering the mind and psychology of the artists,” del Guidice said. “Surrealism gave the artist permission to look at the psychology of the individual, think about their emotions, their socioeconomic condition — things that were begun by Goya but then really licensed by surrealism. You can see that in Sessler. We quote him saying that he was always a fighter for the underdog.”

Milwaukee-born Alfred Sessler (1909-1963) is a much-collected artist who taught at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and founded the school’s famous graphics program. There he developed the “reduction block” method of printmaking, which allowed multicolor printing with a single block.

Sessler has two haunting works on display in this exhibit: “Clown Head” and “Sad Face.” Del Guidice perceptively notes how much “Clown Head” resembles the Kaiser, the “friend” created by genetic designer J.F. Sebastian (William Sanderson) in Blade Runner. “Sad Face,” she said, “drips with sadness.”

It’s not surprising to find a Charles “Chick” Peterson piece in the collection, but the subject matter of this early work is surprising: a beaten-looking man walking a wet, hyper-realistic road along a vague landscape. It’s a large and impressive work.

“Chick is such a master of detail,” Meissner-Gigstead said.

“It’s a beautiful painting,” del Guidice said. “You can just feel how wet that road is.”

That realistic detail of the road in Peterson’s work is one of the unspoken tenets of surrealists.

“They absolutely, tooth and nail, held on to the idea of realism. They were high-realist painters,” del Guidice said. “Everything is identifiable with something you understand, but the assemblage of it is so unlikely and magical. It’s imbued with a sense of imagination and magic. You can’t count on any one element to be honest with you. It’s playing with what you expect and what reality is.”

Chick Peterson is not the only Door County artist represented in the exhibit — del Guidice said a quarter of the 44 works are by county artists. Some of them are in the Exquisite Corpse section of the exhibit, which features scrambled creature parts (head, torso and legs) — some human, some not.

Exquisite Corpse began as a surrealist parlor game, using either art or writing.

“It’s probably one of the most well-known surrealist tools,” Meissner-Gigstead said, adding that she employs the game with student visitors.

Speaking of children — for whom this exhibit is appropriate if they like to ponder the sweet mysteries of life — Meissner-Gigstead said there are surrealist activities for them.

The exhibit will close Sept. 16, but because these works are part of the permanent collection, you may see them anytime. The small staff appreciates a day’s advance notice of what you would like to see, however.

The Miller Art Museum is located in the Door County Library, 107 S. 4th Ave. in Sturgeon Bay. Hours are Monday, 10 am – 8 pm; and Tuesday through Saturday, 10 am – 5 pm.