The History of Us: Egg Harbor’s Family Histories

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

A version of this essay appears as the introduction to the two-volume collection of family histories, Celebrating Egg Harbor.

“History,” Winston Churchill said, “is written by the victors.” It might also be said that it is told through the prism of success. Too often, the interpretations of our past come from those who made fortunes, those who won wars, and those who sat on the ladder’s top rung.

Told from this perspective, “our” telling of history does a great disservice to the reality of our collective experience.

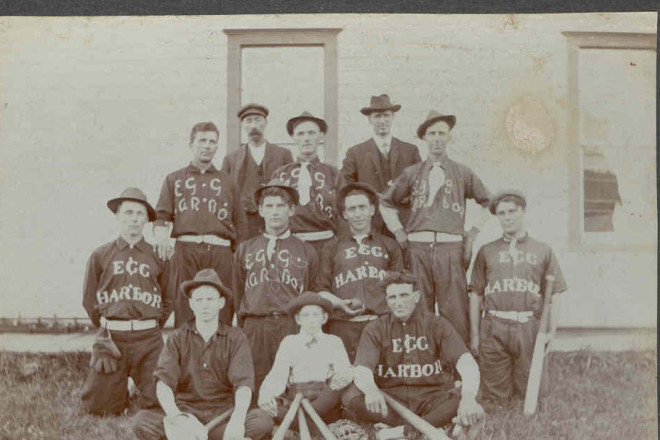

When I read the compilation of family histories collected by the Egg Harbor Historical Society this spring, I read the stories of toil, of hardship, and of perseverance as experienced by the rest of us, of ancestors who may not have made themselves wealthy, but did make themselves a life and their families a future. These stories, ignored by history textbooks and scriptwriters, are no less remarkable than those of barons and politicians.

The Egg Harbor Historical Society has compiled a collection of family histories in Celebrating Egg harbor.

The story of Egg Harbor is the story of men like Ferdinand Jorns, the son of a German shipbuilder who, in 1857, boarded the ship Sunshine out of Hamburg, Germany en route to the United States. He was among the first trickle of immigrants who would eventually find their way to an outpost on Wisconsin’s isolated peninsula. It’s also the story of the Carmody brothers, Thomas and William, who arrived from Limerick, Ireland via Quebec in the 1870s and began clearing woods in what would become Carlsville.

They were followed by John Bertschinger, who left his wife and three young sons behind in Rotherist, Switzerland in 1881 in search of a better life for them all in the United States. At about the same time that Bertschinger sent for the rest of his family in 1884, a tailor and traveling salesman named J. George Bittorf fled the Saxe-Weimar Republic of Germany with his eldest son to keep him out of military service.

These men and women came from Ireland, Canada, Prussia, Luxemburg, Austria, Germany, Poland, Switzerland and Sweden, leaving their homelands far behind, most of them never to return. Some of them fled fighting, others sought religious freedom, but most left in search of land and opportunity.

I grew up in the town they created. As a kid I rode my bike down the roads they cut out of the woods and I played in the fields they once worked so hard to harvest. For a time we lived in what once was a lumber mill, and my parents ran a store where a tavern called the Anchor Inn (now Liberty Square) once lured thirsty farmers. Still, I knew little of where these places came from or the people who built them.

As I read these family histories, I found myself repeatedly drawn back to the vision of this disparate collection of new arrivals carving out a life in an untamed landscape. A vision of loggers and farmers building homes and businesses far from the urban world and a lifetime away from their families in Europe. They had no visioning sessions, no master plans, no consultants to teach them the latest “best practices.” What they had was a collection of different cultures, languages, and religions not far removed from the battle lines of Europe, but united by their struggle to make a new life. They created the community of Egg Harbor organically, relying on their own ingenuity to rebound from demoralizing setbacks.

Yet within that struggle, one that required all the hands of large families to make clothes, fetch water, and pull tree stumps, this mélange of settlers could somehow see beyond the hardscrabble days to a future that would be much different than the lives they were living.

Egg Harbor’s early arrivals valued education rom the moment they claimed their slice of the peninsula, establishing in 1855 the first of what would become at least a half dozen different elementary schools within the township. Though there was backbreaking work to be done building roads, homes, farms and businesses, these early settlers made building schools for their children a priority. They built grade schools called Sunny Point, Pleasant Grove, Horseshoe Bay, Egg Harbor District #1, Pershing and Carlsville, sending their children to walk miles to the one-room schools even though so much work begged to be done at home.

One hundred fifty years later many of the schools they built still stand, many of their storefronts still beckon customers, and their taverns still quench the thirst, though in service to a far different clientele than they might have imagined. Impressive as those tangible monuments to the past are, they have little meaning and don’t come to life without the stories of the families that built them.

In reading the family histories collected by the Egg Harbor Historical Society for its two-volume collection celebrating the community’s 150th anniversary, I found myself surprisingly moved. The stories are those of people who built a life, and a town, from nothing. They are the stories of America seen through the prism of the small town we call Egg Harbor, Wisconsin.

We live in a time when most of us feel like the rug could be pulled out from underneath us at anytime, when we ask what we will do if Wall Street tells us we’re doomed. These stories reminded me that the answer isn’t locked in the halls of academia.

Those answers are in our own local history, the history beyond the victors – the history of us.

Myles Dannhausen, Jr. was born and raised in Egg Harbor, where he spent most of his childhood in his parents’ small, century-old home on the corner of County T and Maple Road.