Time to Leave the Lakes Alone

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

After a century and a half of trying to control the Great Lakes, is it time to concede to Mother Nature?

Bryan Nelson stands on his wooden boardwalk over Lake Michigan, about 100 feet from shore. Well, 10 years ago he’d be standing over Lake Michigan water. Today, he’s surrounded by tall grasses growing from a soft, muddy sludge as he looks back toward his home and business on the Baileys Harbor shore.

Since 1996, Nelson and his wife, Joan Holliday, have owned the Blacksmith Inn on the Shore. Back in the late 1990s, the inn featured a 400-foot stretch of picturesque sand beach just a few steps from the inn’s back door. Today, that beach looks more like a jungle, with thick bushes and trees climbing over our heads and grasses taking root in the sludge.

“Eight or nine years ago, we stopped saying beach in our marketing or even on the phone,” Nelson explains with a shrug and a resigned smile. “We don’t want to oversell or mislead people, so we say we have a ‘wild shoreline.’”

The Door County shoreline changed rapidly from 1999 to 2003, and that change is on dramatic display in shallow Baileys Harbor. The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources defines the edge of Nelson’s lawn as the lake’s high water mark. At the end of the 1990s, Nelson’s property was hit with the duel impacts of Mother Nature and human modification to the shore. The water began to recede at the same time that Baileys Harbor completed an expansion of its town marina just a few hundred feet from Nelson’s beach, causing sediment to build up and catch. Then, the water retreated 80 feet in 2002 and another 160 feet in 2003. By the time the water level at Nelson’s property stabilized a bit in 2003, it had receded hundreds of feet from the high water mark.

Many shoreline property owners are demanding that something be done to bring water levels back up with controls in far-flung parts of the Great Lakes system. Nelson hasn’t joined that chorus.

“We keep messing with the lakes, and we keep screwing it up,” he says. “Sure, my first instinct is to say, ‘Yes, we should do something,’ but I’m not so sure. What do we really know? We’ve only been keeping records for 140 years. There’s much more that we don’t know than what we do know.”

The Ephraim Shoreline had receded hundreds of feet by 2009. Many piers don’t even extend into the water. Photo by Dan Eggert.

Nelson has worked on the shore of Lake Michigan for 30 years, dating back to his days at Anchor Marine in Sister Bay in 1980. He was there in 1986, when Lake Michigan reached its peak water levels and lake seiches, or storm surges, “brought the lake into the parking lot.”

At that time, people were “up in arms” clamoring for regulation of the entire Great Lakes system, but back then it was because the high water levels were creeping in on their property and threatening shorefront homes. Some homes on the shore near Milwaukee were lost, and property owners built retaining walls and installed riprap to save their land and their homes.

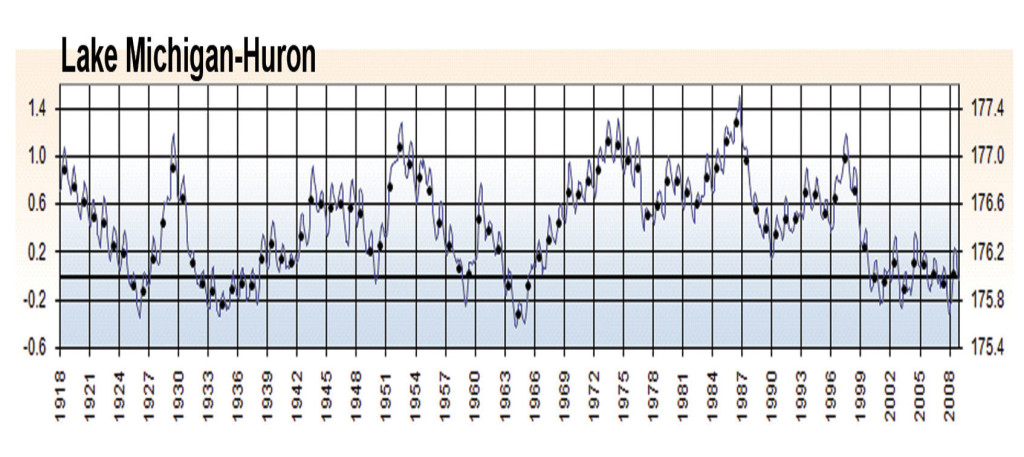

In response, the International Joint Commission (IJC), the bi-national commission of United States and Canadian representatives that oversees regulation of the lakes, initiated a study that examined the possibility of regulating the entire system. Its study was completed in 1993, near the end of a 30-year period of unprecedented high water levels. The authors ultimately recommended against implementing system-wide controls, calling them too costly and carrying no guarantee that engineering could keep up with Mother Nature.

In 1986, Door County residents feared high water levels could damage homes. Graphic courtesy of the International Upper Great Lakes Study Board.

Twelve years later, the commission was taken to task again, this time by shorefront property owners watching their piers become useless amidst the retreating waters. The Georgian Bay Association, a group of Canadian property owners, commissioned a study of their own in 2005. They hired Baird & Associates, an international engineering firm that focused its research on the 97-mile St. Clair River, which connects Lake Huron to Lake Erie. Their study determined that dredging of the St. Clair riverbed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in 1962 altered the river bottom so drastically that it led to continued erosion in the years to follow.

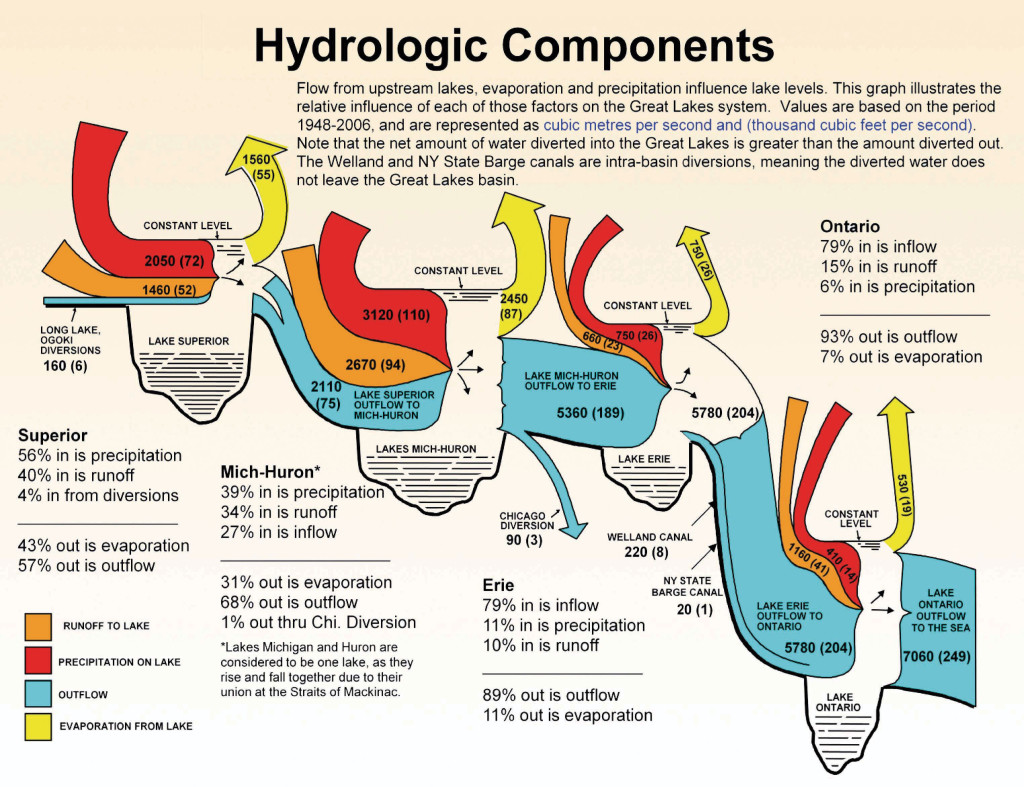

That erosion, the study claimed, increased the flow of water from Lake Huron to Lake Erie, draining vast sums from lakes Michigan and Huron (which hydraulically are considered one body of water). The study ignited international controversy.

In response, the IJC conducted an exhaustive, $3.6 million study of its own, led by Dr. Eugene Stakhiv, co-chair of the International Upper Great Lakes Study board. Its findings were released in July of 2010 and disappointed many concerned about lake levels. The real water thief in the last quarter-century, it determined, was not the St. Clair dredging, but climate change, particularly a drop in rain and snowfall in the Great Lakes Basin.

“We’re just not seeing these storm systems the way we used to,” says John Nevin, policy advisor for the IJC study board. A Rhinelander, Wisconsin native who now lives in Michigan, Nevin said the near-drought conditions in the Great Lakes basin from 1998 to 2007 sapped the lakes of the precipitation that feeds the system.

But the IJC study didn’t lay the issue to rest. At a public hearing with three members of the IJC in Sturgeon Bay in April, 2010, a crowd of 120 people was united in their passion to have controls put in place or remedial measures, such as infill, an inflatable bladder, or dams on the St. Clair River.

Frank Forkert of Liberty Grove argued for economic stability, pointing out that much of the region relies on the lakes for its livelihood through boating, fishing, tourism, and shipping.

Dr. Stakhiv says controls have been discussed at several points, but the difficult question remains: What is the trigger point that makes you implement such a device? “It is impossible to find the golden mean,” he said. “We have proposed fixes, but when we go to the public [with a solution and its costs], almost invariably they say, ‘do nothing.’”

The lakes have been altered over the past century by numerous dredging projects, locks, channels, and controls. Each effort to fix one problem or benefit one area inevitably has an adverse impact somewhere else. In 1900, engineers reversed the flow of the Chicago River to send the city’s sewage downriver to St. Louis. Now the river drains an estimated 2.5 billion gallons of water from Lake Michigan each day, and has opened the door for the Asian Carp, an invasive fish that many believe could devastate the Lake Michigan ecosystem.

In 1959, the St. Lawrence Seaway opened to tremendous fanfare, connecting the Great Lakes to the Atlantic Ocean. It was an engineering marvel that brought ocean-going shipping and economic growth to port cities. But 30 years later a startling influx of invasive species began that continues to alter the lakes in dramatic ways. Zebra mussels, quagga mussels, and grasses are just a few of the more than 60 foreign species that have bummed rides into the lakes on oceangoing vessels.

From the late 1800s through 1962, the St. Clair River was mined for resources and then dredged for the shipping industry, draining as much as 21 inches from lakes Michigan and Huron. Now, with water levels so low that Door County property owners have dredged 367 private channels to access piers and ramps, many want to reverse the effects.

Though the initial St. Clair River study was only instructed to look at post-1962 dredging effects, the public outcry for a fix has pushed scientists to dig further. The U.S. and Canadian governments have given the study board a mandate to look at remedial measures due to climate change, but not due to dredging in the St. Clair River. But Nevin says we may just be chasing our tail.

“These all have ecological consequences,” Nevin says. “What would it do to Lake Erie? We can’t make a precipitous decision based on a couple of years of low water levels.”

The late Phil Keillor, who was a leading lake expert for the University of Wisconsin Sea Grant Institute for 30 years, sounded an ominous warning in a 1997 report. Climate change is affecting the paths of storms and is changing precipitation times and levels, he wrote. The unforeseen high water levels of 1986 “washed away an assumption that lake level regulation and human modifications offer enough control.”

He added that “the view that data on storms and water levels occurring in the first three-fourths of this century are adequate for predicting future storms and water levels on the Great Lakes was a casualty of the high water level crisis in 1985 and 1986.”

In other words, in a changing climate the past is a poor model for measuring the future. The world has experienced three of the warmest years on record in the last decade. On the Great Lakes, this means the lakes don’t freeze over, and evaporation continues over the winter when ice once put a lid on them.

Scott Thieme, Chief of Great Lakes Hydraulics for the Detroit District of the Army Corps of Engineers, says there are two schools of thought on managing the lakes – keep messing with the lakes until we get them under our thumb, or pull all the controls out and go to a natural flow. Thieme doesn’t like either.

“I think right now, to try and do something is extremely expensive,” Thieme says. “I’m not sure the St. Lawrence would get through today. We really didn’t talk about the environment back then when it was built.”

Then there’s the unknown: climate change. Experts say that the effects of climate change are becoming more pronounced. Last winter’s snow on Lake Superior was the lowest ever recorded, but then June saw record high levels of precipitation. “We’re in for an era of extremes,” Nevin says. “The climate change models are all over the map, and though the consensus has been that lake levels will go down, some models have them going up. The science is imprecise.”

Thieme says that if one broadens their vision to look 25 or 50 years out, it puts the limits of human ingenuity in perspective.

“If we’re complaining right now, what if lake levels drop another two to three feet?” he asks. “We might see major changes in navigation and public safety. Maybe we set another record high in 20 years. In 2007, when we had the record low for Lake Superior in August, we got 10 inches of rain in September. So as soon as we opened our mouths we were putting our foot in it.”

Thieme referred to a study he read that said Great Lakes shoreline property changes hands, on average, every seven years, which may cause a bit of a short-term memory problem when it comes to lake levels. People expect their property to stay the same as the day they bought it, no alterations by the neighbor, no new zoning guidelines, and certainly no change to their shoreline.

Lake levels on all five Great Lakes have been below average for the last 10 years. But beginning in the mid-1960s they were above average for the better part of three decades.

“A lot of people got used to those 30 years,” Thieme says.

In our never-ending quest for solutions, we rarely stop to consider whether doing nothing at all would be more financially sound in the long run. It’s not in our nature. But everything we do on the lakes to boost the economy of one region or another seems to cost someone else, and everybody else further down the road.

“Being an engineer and thinking we can control things,” Thieme says, “has taught me that every time you think you can do something, Mother Nature comes back and shows you up.”

In 2010, water levels rose dramatically from the lows of just a year earlier. Photo by Dan Eggert.

Back in the late 1980s, Keillor appeared at a forum about high water levels at the Sister Bay Town Hall. Something he said then sticks with Nelson to this day. “Humans influence,” Nelson recalled Keillor saying as we made our way back up the boardwalk toward his old shoreline, “but nature controls the water levels of the Great Lakes.” Consider, for instance, that more water evaporates from Lake Superior in a single day than flows through the St. Clair River all year.

As Nelson and I walk back toward the inn, I ask him if he worries about the effect the slipping lake level has on his property value. “I’m sure I’ve lost a little bit,” he says, “but that pales in comparison to the big picture.”

We enter into the “jungle” portion of his wild shoreline, where trees, grass, and bushes form a canopy over the boardwalk. Nelson finds the beauty in Mother Nature’s change.

“This is filled with birds,” he says. “It’s essentially an extension of the Ridges Sanctuary. If it weren’t for the loss of the beach I think you’d say it’s really quite beautiful.”