Vampire of the Sea: Without sea lamprey controls, the Great Lakes would not be so great

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

“Lampreys in such vast numbers that the water literally teemed with them invaded Green Bay early this fall bringing fishing operations practically to a standstill. All important commercial species were attacked, and so great was the destruction that dead and dying fish littered the surface of the water. Fishermen of northern Green Bay, discouraged by dwindling catches, by the presence of large numbers of lampreys in their nets, and by the necessity of discarding the high percentage of mutilated fish in the catches they did make, removed most of their gear from the water by the end of September.”

– The Fisherman, fall 1953

The horror story of the sea lamprey invasion of Green Bay has been repeated throughout the Great Lakes ever since the parasitic Atlantic Ocean native made its way through the Welland Canal and first appeared in Lake Erie in 1921. Fifteen years later the invasion had spread to Lakes Huron and Michigan, and by 1938 the sea lamprey was also calling Lake Superior home.

A sea lamprey on a whitefish caught by a commercial fisherman. Photo by Jim Legault.

A number of factors contributed to the growth of its population, including an abundance of host fish, a lack of predators (humans being the only one), plenty of spawning habitat and high reproductive potential — a single female can produce as many as 300,000 eggs during her reproductive phase.

Lamprey belong to a prehistoric class of jawless fish known as agnathans. Only two species have survived — lamprey and the destined-for-disdain hagfish.

Lamprey have suction cup mouths they use to cling to their host and feed on blood and other bodily fluids. Their mouths are filled with rows of sharp teeth in concentric circles that help to induce the blood flow of their victims. They have no other way to live on this earth.

But, as its name implies, the sea lamprey is not from these parts. It’s an ocean parasite that normally attaches to fish and mammals much larger than our native Great Lakes fish. We can only imagine the thoughts of the first angler who caught a native fish with a sea lamprey attached to it back in the late 1930s or early 1940s.

The invasion was on.

The sea lamprey is widely regarded as the most invasive of all the invasive species to find their way into the Great Lakes. Lake trout were particularly devastated. Before the invasion, as much as 15 million pounds of lake trout were harvested annually from the Great Lakes. By the 1960s that figure dropped to 300,000 pounds. It’s estimated that half of sea lamprey attacks result in death for the host fish.

“It’s an alien invader. It’s like nothing ever seen before,” said Cory Brant, a postdoctoral fellow in the Graham Sustainability Institute at the University of Michigan–Ann Arbor.

Brant has spent nearly a decade studying the sea lamprey. His master’s and doctoral research involved studying and isolating the pheromones that attract sexually active sea lamprey.

“They have what I call a love cocktail that nothing else can detect,” he said. “Our goal is to isolate, detect and essentially use [the pheromones] as a chemical lure, just another tool in our toolbox for sea lamprey control.”

And sea lamprey control “is essentially holding this ecosystem together. Cut it off and you just don’t have a fishery,” Brant said. “It’s a very big story.”

“Without sea lamprey control there would be no sport fishing on the Great Lakes,” confirmed Mark Holey, who recently retired after a 25-year career with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service that included working with sea lamprey control.

“Can you tell me of a sea lamprey problem?” Holey asked before answering the question himself. “No, maybe not like you used to be able to tell, but that’s because they’re spending around $15 to $20 million a year to manage the number so you can have these fisheries.”

Holey said the folks who work in sea lamprey control described it to him as a sort of whack-a-mole.

“You whack ’em down here, and they pop up here,” he said. “You hope you have enough money to whack ’em down enough so you have sport fishing.”

If the funding is stopped, as has been threatened in recent years, Holey said there is no doubt about what will happen. “We will lose everything.”

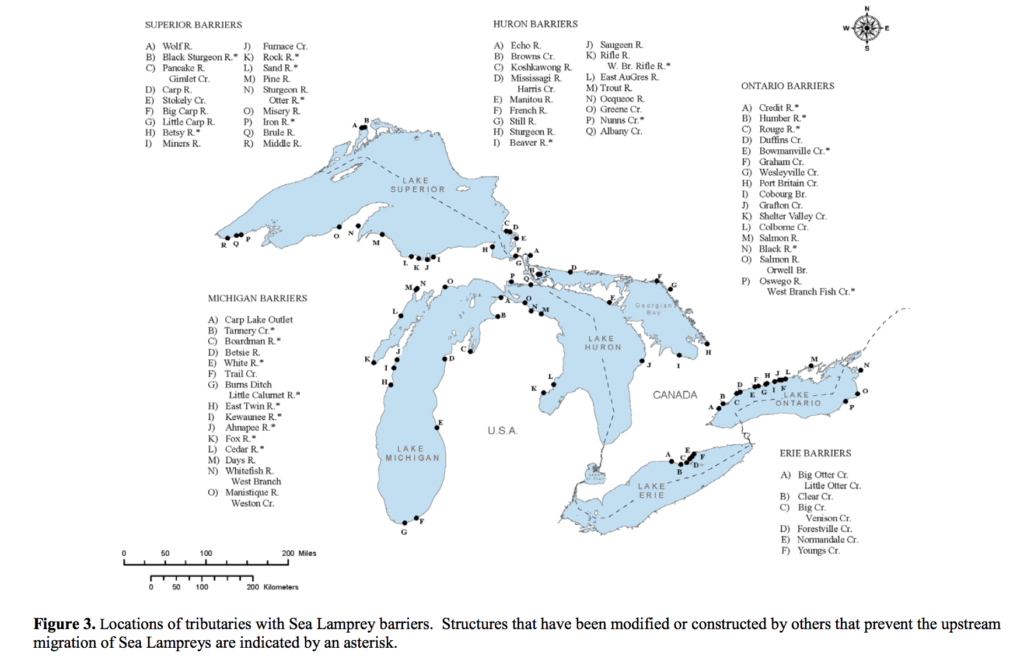

Control efforts include the use of lampricides in tributaries that target sea lamprey larvae before they have transformed from filter feeders into parasites; strategic barriers that prevent the lamprey’s limited jumping ability but don’t stop fish from jumping over; trapping; and the use of pheromones and “alarm” cues that dead or injured lampreys emit to warn other lampreys of impending danger.

That big story of the sea lamprey has been very much on Brant’s mind the last few years while he has refocused his attention on writing a book and producing a documentary about the various sea lamprey control efforts going on throughout the Great Lakes.

So this biologist who got his start in the Fisheries and Water Resources, Biology and Aquaculture program at the University of Wisconsin–Stevens Point has switched his focus to oral history and storytelling.

“The goal was to collect stories from individuals who pioneered sea lamprey control,” Brant said.

He has certainly succeeded in harvesting those stories, but they have come with detours.

“I’ve been at it about three years now,” Brant said. “I’ve been all over the Great Lakes basin talking to people.”

Which is a huge shift for this sea lamprey researcher who said he used to spend his time doing field work in the middle of a state forest at night or in the lab studying lamprey physiology.

“I never got to work with people,” he said. “I’ve always loved stories and the power of engaging people with stories.”

Because Brant’s mind was open to what he called “the power of stories,” and he had no fear of taking the detours away from his sea lamprey control research, he ended up with what he calls “a rich history of the Great Lakes” that includes stories about the Great Depression, World War II, shipwrecks, commercial fishing, as well as jokes and tales from what he described as “a bygone era.”

He can talk about the physiology of fish to people all day, but when he started hearing the stories told by the old salts whose lives are invested in these Great Lakes, he saw the bigger picture of “a time when people were more connected to the water.”

But the researcher in him ominously added, “and then the lamprey raised its ugly oral disk.”

The documentary was in production when we spoke. Brant hopes it will eventually air on public television stations around the Great Lakes. The book was under review by the University of Michigan Press.

Brant said the book was finished except for one chapter, which he said will be a synthesis of all the lessons he has learned and “experiential knowledge” he has gathered about dealing with this particular invasive species and invasives in general.

“Some of the people I talked to have valuable lessons that I think are going to be really important looking at the future of invasive species control,” he said.