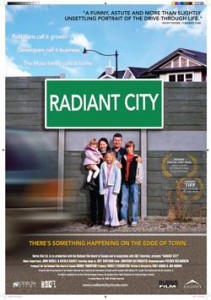

Watch This: Radiant City

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

Gary Burns has lived his entire life in Calgary, Alberta, Canada, a city he said is “basically defined by its suburbs.”

He grew up when it was a small city of about 200,000. As he approaches 50, the city is now home to nearly one million people.

“I’ve always been critical about what I see around me, and Calgary has grown amazingly, and I think, very badly,” he says.

Burns and his co-writer and director, journalist Jim Brown, decided to use actors in his documentary, Radiant City, a different tactic that stretched the boundaries of the genre.

“The idea of following a family around for a couple years to tell the story would be the normal way to go,” he says. “But no matter what happens, you just end up using what you want to use anyway. So we felt like, why not just be honest about it and use actors.”

The film was obviously produced to make a point, and Burns doesn’t hide behind over-wrought claims of artistry.

“We wanted to get people talking, try to fool people and piss people off a bit,” he says.

Burns said it wasn’t hard to cast, since most of Calgary’s actors actually live in the suburbs, the only place they can find affordable housing. Those actors brought their own stories of life in the suburbs to the film, which Burns leaned on for the story.

It takes only a few seconds of viewing to see that Burns is no fan of suburbia.

“They’re not designed to be lived in,” he says. “The people who designed them wouldn’t live in them. They don’t use new urbanist models. There’s no bar, no corner store, no coffee shop. Most have one main street with a gas station and convenience store, and that’s where people go. Otherwise they drive off in their cars to the big box stores.”

Oh, the big box stores. Burns parodies them and the life that revolves around them in hilarious fashion, and he’s stunned that towns still clamor for them.

“As soon as you allow big box stores to come in, your core is dead,” he says. “Give people a taste and they love it. You can see it coming. It doesn’t take much research.“

With the housing market collapse, and the energy crisis swelling underneath, large communities are repurposing increasingly empty suburbs. Meanwhile, the developers are moving on to small-town prey.

“So you have people retrofitting the suburbs, trying to bring back the small-town feel,” Burns says, “and at the same time, you have the small towns bringing in big boxes and going the other way.

So who’s to blame?

“We all need a little education,” he says. “But the developers and cities themselves are allowing it to continue. A lot of people are pretty short-sighted in local government. The only people who could stop it are the city. They have the power but they don’t use it.”

In Calgary, the city was growing so fast in the 1990s and early part of this decade that the city could barely keep pace. With 20,000 people moving in each month, Burns said the city was pushing, almost begging, for more sprawl.

“The people moving to the suburbs are almost like prey,” Burns said. “They can’t imagine living in a townhouse or anywhere downtown, it’s like the advertising won’t let them, telling them [Burns goes caveman here] ‘We need house.’”

As evidence that people are victims of a snow job, Burns poses a telling question.

“Where do people go for holidays?” he asks, and gives a quick answer. “They go to New England, or Aspen, or any other place that has that small-town feel. Nobody vacations to the suburbs.”

Some, like James Howard Kunstler, the author of suburban critiques The Geogrophy of Nowhere and The Long Emergency who is featured in the film, believe the suburbs will die as energy becomes scarce and travel prohibitively expensive. Burns sees a new suburbia, however, not a dead one.

“They’re not going to go away,” he said. “Some people will live there and work from home, some will simply move to different suburbs closer to work. Right now, people don’t even think about driving long distances, but when it costs $300 a month just to drive to work, people will at least think about it.”

Did the film have the desired impact?

“A lot of people saw it,” Burns says. “In a lot of ways it’s preaching to the converted.” The director pauses, and allows a light chuckle. “But, it’s a great tool for the converted anyway.”