Black-capped Chickadee

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

If one were to conduct a popularity contest regarding the wild birds of the forest, attempting to determine the one that is most widely-recognized and enjoyed, which do you suppose it would be? My vote would go to a pert, friendly, little feathered gymnast, the one the American Indians of this region called “ch’geegee-lokh-sis,” the Black-capped Chickadee.

Residents of Maine and Massachusetts chose this nimble creature as their state bird, and rightly so.

The Black-capped Chickadees live there year round, as they, of course, do in many other states. The northern forest states, however, can by no means lay sole claim to these cheerful acrobats. A wide range of environments include the chickadees – deciduous to coniferous woods, highlands to lowlands, wetlands to drylands. Our region experiences an increase in their numbers every winter, down from the north because of the shortage of food there.

These trusting, roly-poly birds reach the peak of their birdfeeder activity in winter. Only an occasional one or two are seen at our summer feeders, while a dozen or more chickadees, in addition to other birds, look for a handout on a typical winter day. During a two-day period in the early spring of 1967, I captured a total of 53 chickadees in my mist nets for scientific study and banding at The Ridges Sanctuary where I was living and working. I was a volunteer, federally-licensed bird bander at the time.

Imagine my surprise and joy when, in late October of 1973 while banding birds at The Ridges, I recaptured one of those chickadees banded in early 1967. Obviously the bird was hatched during the summer of 1966 or earlier making it seven or more years old. One of the things that interested me was a definite growth of tiny grayish feathers mixed in with the black head feathers. The record age of a Black-capped Chickadee at the time, as far as I could determine, was nine years.

Banding, weighing, and measuring nesting chickadees from different latitudes in North America has proven that those in the north tend to have larger bodies, giving them less body area in proportion to their weight. This fact helps them to survive in extremely cold temperatures. Another recorded discovery is that the northern birds’ beaks, legs, and wings tend to be shorter than those of the southern birds. These extremities lose heat more rapidly than the larger parts of the bodies.

Here are other interesting facts: A chickadee’s heartbeat speeds up as the surrounding air temperature decreases. An active feeding chickadee on a sub-zero day can be expected to have more than 1,000 heartbeats per minute. Its heart slows down to about 500 beats per minute when it is asleep. During the 14 or more hours spent at night in its roosting cavity, its body temperature also goes down, enabling the bird to use nearly 20 percent less energy in remaining alive during the extreme cold.

I was quite impressed the first time I removed a chickadee from a mist net. Ed Peartree, licensed bander of Oconomowoc, was teaching me the art of mist netting. After a couple of weekends of watching him, he finally allowed me to remove my first bird, a chickadee. What a scrapper! What an initiation I received: Its body seemed to hum or vibrate in my hand – little did I realize then what its normal heartbeat was.

Talk about quickness and maneuverability! Stroboscopic studies of this speed merchant show that it can change its direction of flight in three-hundredths of a second. Its wing beat – about 30 per second – enables it to accomplish this rapid change of direction.

Nearly everyone knows the field marks of the chickadee, its black cap, white cheeks, black bib, grayish back, and the brownish wash of its flanks. It is generally thought that the sexes are not distinguishable. But banders, having handled and measured thousands of these birds, think it may be possible to tell the males from the females. The black cap of the male appears to extend farther onto its back than does that of the female. Also, the male’s bib is wider, especially right beneath the beak, and the bottom line of the male’s bib is irregular and tends to “feather” into the grayish breast. The female’s bib is squared off at the bottom.

Despite all these distinguishing marks, one of my friends proposed the following toast to these little beady-eyed friends:

Here’s to the chickadee,

The sexes are alike you see.

It’s hard to tell the he from she,

But she can tell, and so can he!

These seemingly carefree birds sing two well-loved melodies. Its “chick-a-dee-dee-dee” call ranks first, followed by its high, piercing, far-reaching “WHEE-dee-dee” song. On hearing this latter song, scores of people confuse it with that of an Eastern Phoebe whose song is very abrupt, wheezy, and not as musical as the chickadee’s. We’ve heard this chickadee whistle in every month of the year, but much more so in spring and early summer.

Students from the University of Wisconsin – Milwaukee tape-recording birdcalls at the Cedarburg Bog Field Station were able to associate about 30 different combinations of chickadee calls, songs, and notes with an equal number of actions, feelings, and mannerisms. Quite a vocabulary for such a tiny bird!

The fact that so much of its winter diet consists of the eggs of harmful insects makes the chickadee a favorite friend of farmers and orchardists. The primary food that keeps these birds returning to our and many others’ feeders is the black oil sunflower seed.

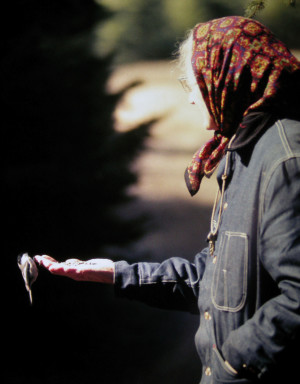

Of all the chickadees that have trustingly eaten sunflower seeds from our hands, as many or more could not be persuaded to trust us. Some will impatiently fly to one of the empty feeders and rap sharply against the sides, over and over, while others gladly take seeds directly from us. I like to think that the obstinate ones are saying, “Okay buddy, hurry up with those seeds. Don’t think for one moment that we’d take a chance sitting on your hand!”

Chickadee, rest assured that we trust and respect you as one of our dearest friends.