County to Add Cave to Park System

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

County officials hope to have Horseshoe Bay Cave open for its first student tour in September.

And who wouldn’t want to crawl into a dark, cold, muddy, damp and frequently confined series of fissures in the Niagara Escarpment that are home to 1,250 bats, who knows how many spiders, mysterious isopods and other equally creepy cave-dwellers?

Thanks to a Wisconsin Coastal Management grant, Door County owns the entrance to the cave, while the rest of it snakes under Horseshoe Bay Golf Club property, making it the owner.

On May 20 at the Horseshoe Bay Golf Club, the Door County Airport & Parks Committee got a virtual tour of the cave, thanks in part to an actual tour of the cave made by Corporation Counsel Grant Thomas and Bill Schuster, head of the county Soil and Water Conservation Department, as well as many forays made by Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources cave and mine expert Jennifer Redell.

Airport & Parks Committee members Ken Fisher and Charles Brann study the straw-colored African fruit bat that Jenifer Redell brought to the special committee meeting held to talk about the Horseshoe Bay Cave management plan. Photo by Jim Lundstrom.

Redell, Schuster, Thomas and county Parks Director Erik Aleson tag-teamed in briefing the committee on a management plan for Horseshoe Bay Cave and on its importance as a home to a subterranean civilization of amphibians, insects and the only mammal that has the ability to fly – bats.

Bats, according to Redell, are underappreciated, undervalued and understudied, even though we do know that, with their ability to daily eat their weight in insects, they collectively provide $658 million to $1.5 billion annually in insecting services here in Wisconsin.

The 1,250 bats that hibernate in Horseshoe Bay Cave during the winter are increasingly important as the bat-killing white-nose syndrome makes its way into Wisconsin (the fungus was discovered in Wisconsin in March on bats hibernating in an abandoned mine in Grant County). The fungus thrives in the moist cave conditions that bats need during their hibernation in the months when there are no insects to feed on. Once infected with the fungus, Redell said a bat colony has a 95 percent mortality rate.

Redell even brought along a couple of bats to show the committee, including a big brown bat, a species native to Wisconsin and one of four species that calls Horseshoe Bay Cave home for at least part of the year, and a much larger, non-native straw-colored African fruit bat.

Besides serving as a habitat for bats and other creatures of the dark, Bill Schuster said Horseshoe Bay Cave holds biological, geological, hydrological, meteorological and historical information for scientific study. He described the tourism aspect of the cave as “a rugged access tour.”

“Horseshoe Bay Cave is never going to be Mammoth Cave,” Schuster said, referring to the central Kentucky cave system that was turned into a national park in 1941 and attracts more than a half-million visitors annually.

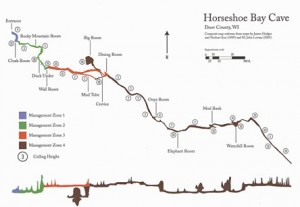

The management plan splits the cave into four access zones that are dictated by safety for visitors and conservation concerns. Zones 1 and 2 can be visited without much more than hard hats, but visits to Zones 3 and 4 require specialized gear and wetsuits. Cave visits would only be allowed during non-hibernation period, from mid-May to the end of September. Trustees will be trained to lead the tours, with no more than 10 visits weekly and no more than 12 people allowed to tour Zones 1 and 2 at one time. For Zone 3, there would be no more than five trips annually, and because of the difficulty, background checks will have to be done on those who apply for Zone 3 in order to ensure they have the experience to negotiate its demands. Zone 4 would be reserved for scientific research and special access requests that would go through the county Parks Department.

The committee talked about making access to the entrance of the cave more accessible, but the draft plan calls for no modifications in the cave, which didn’t sit well with Bryan Kleist of Appleton, vice chairman of the Wisconsin Speleological Society, who attended the meeting to voice opposition to the plan’s no modification policy.

“We don’t think the current plan is the best route to go,” Kleist told the committee. “I think it is unfair.”

He said digging out the glacial sediment in the first 75 feet of the cave would allow greater accessibility for a larger portion of the population.

Phase 1 of the plan means the draft plan will go before the Airport & Parks Committee when it next meets at 9 am on June 18 at Cherryland Airport, Sturgeon Bay, and then to the full County Board on June 24.

Phase 2 is what Corporation Counsel Thomas referred to as “the boring legal stuff,” working out an access agreement with Horseshoe Bay Golf Course. Phase 3 involves trustee training, seeking funding for gear acquisition, developing a safety strategy and cave monitoring program.