The Eye-Catching Artwork of David Franke

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

Maybe you have already seen the striking pieces of avant-garde Door County artist David A. Franke, and maybe you have not yet had that chance. If you have, however, it is almost certain that they have seen you too…

“I think if you can look at the world and see some wonder in it, it will become a world that…you want to preserve.” Door County artist David Franke. Photo by Len Villano.

Franke — who you might generally find at PetPourri, the pet grooming parlor on Highway 42 where he acts as “humble, lovable assistant” to his wife, Kathy — exercises his own creative abilities using a variety of media, from the usual paint and ink to the more unique burnt-out light bulbs, deer bones, and, perhaps most notably, prosthetic eyeballs.

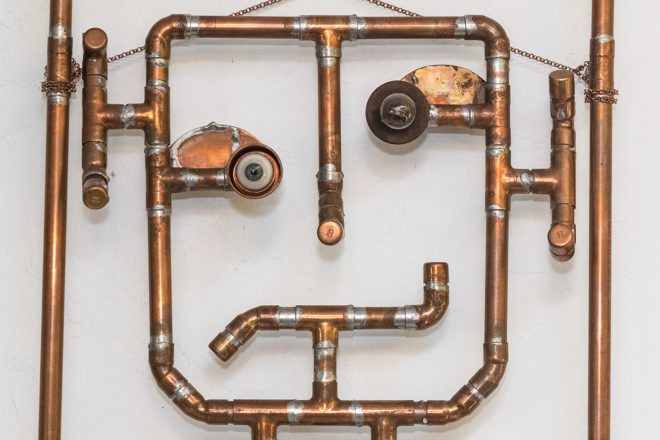

With each one of these materials, Franke always strives to experiment: he brings out bolder hues and livelier movement by putting his watercolors on Japanese Yupo paper (a synthetic product that allows the paints to sit on the surface and mix together rather than immediately soaking in); from habitually walking like his father, “with his eyes down,” he constantly discovers the distinctive branches and stones which form his environmental sculptures and wall hangings; and in the same environmental works, he somewhat paradoxically introduces industrial elements like copper tubing and metal plates.

But regardless what materials, there is a form which seems to appear in nearly all Franke’s pieces — the eye. Although some occurrences are quite subtle, others are uncomfortably obvious. “Most of the time,” Franke assures, “if you look for it, there’s something there that will represent an eye.”

So why eyes? The significance of this image does not consist in a single meaning. Franke refers first to the common idea of a person’s eyes being windows to their soul. He, however, is more invested in another meaning: “I look at the eye from the inside out — so many people look into the eyes to see your soul, your essence…I’m using my eyes to see my world, and interpret my world.”

“Inside Looking Out.” This piece was accepted by the ISEA in 2013 for a show which traveled to Florida, California, and Wales.

It is this active role of the eye, then, which Franke wants to emphasize with his artwork. As he expresses it, the eye is a “lens through which the mind captures the human experience.” But Franke clarifies that our experiences can, and should, be more than merely sensual. We humans do not just take in the colors and shapes of the physical world; we also use what we see to interpret that world. Correspondingly, this symbol of the eye should remind us of our bodily eye, the instrument of physical sight, but also — and even more importantly for Franke — our mind’s eye, the instrument of mental understanding. It is fitting that Franke’s pieces, which unfailingly arrest the gaze of your bodily eyes, also require you to use your mind’s eye in order to really “see” what is there.

Franke’s preoccupation with eyes has lasted for years. In earlier works, he always represented them with marbles: such pieces, he adds, are designed to stand somewhere like a windowsill, so that the “eye” may be illuminated by light — as real eyes are, and as the mind is illuminated by truth. Later, Franke began representing eyes with countless other materials as well, such as beads, bullets and washers.

In 2007, Franke’s optical art caught the eye of one of one of their dog grooming clients, Charlene Berg. “She flipped,” Franke laughs. That summer, Berg insisted Franke display his work in the tower of her Gallery 10 in Gills Rock. He titled this solo show “An Eye for Art” and kept a few pieces on display ever afterwards until the gallery closed in 2012. Since then, Franke has shown his work at several other Door County galleries, including Pangaea and The Hardy.

Many of these pieces play with Franke’s central idea that there is always something for our minds’ eyes to see in and beyond the physical world. This might be something simply imaginative. For example, Franke sees “a lot of faces,” both in natural and artificial things; thus you also will see those faces in his artwork. Or it might be something more intellectual, even spiritual, like how Franke sees in all things the same universal energy. In general, Franke observes, more creative people often tend to “see more in their daily life,” and he considers this a valuable gift. “I think if you can look at the world and see some wonder in it,” he explains, “it will become a world that…you want to preserve.”

“Collateral Damage.” One of Franke’s watercolors on Yupo paper, depicting the inevitable effects of war on the human person.

Franke’s desire to preserve the world and its wonders for “our children’s children’s children,” as he quotes from The Moody Blues, defines much of his work. We must “be kind to our Mother, Mother Earth,” he urges. “We’re treating the earth like we have another planet to go to — we don’t!” Appropriately, despite his artistic diversity, Franke devotes himself most to his environmental sculptures — which not only make a statement about the environment, but also come directly from it. As his wife, Kathy, comparing his work to what one might consider more typical “Door County art,” has put it, Franke “doesn’t paint a landscape — he creates from the landscape.”

His paradoxical propensity to mix in mechanic materials with the organic also relates to Franke’s vision of a better future. He enjoys the “theme of the natural world and the modern world together,” because for him, they ought to be connected. “The direction we should be going environmentally,” he asserts, is “away from coal, and gas, and oil, to wind and solar.” These changes, though, will all take new and innovative technology.

Thus, with his blended art, Franke indicates the means by which we may move forward in our relationship with nature. (Years of work in industrial engineering — which Franke says prepared him for his art career by forcing him frequently to “put things together with spit and baling wire” — may also play into his fondness for incorporating hardware.)

Franke is proud to have received professional recognition for his creations from the International Society of Experimental Artists (ISEA). He became a member in 2006 and a signature member in 2014, after having several pieces accepted to national and international shows that sent his work as far as Wales. Franke looks forward to attaining the next and highest level of membership with just one more show, as well as to opening a gallery of his own in the old retail space of PetPourri, perhaps as early as next year.

“Rust is Also a Color.” One of Franke’s more recent experiments, which won the 2015 ISEA Cutting Edge Award.

Finally, Franke also hopes to continue his latest experiment — painting in rust. His submission “Rust is Also a Color” won the ISEA Cutting Edge Award last fall. This use of an artificial compound undergoing an organic process is yet another example of Franke’s tendency to unite the worlds of man and nature. But Franke further explains the appeal of his new medium by quoting another classic album, this time Neil Young’s — “rust never sleeps,” he reminds us. Rust is all about decay, a slow, inevitable deterioration. Yet, Franke counters, it also adds color to our life, and so too a sort of beauty.

The lesson of rust is particularly easy to remember this time of year, as summer comes to an end and autumn, with its own show of glorious decay, approaches. We should take the change of seasons as a chance ourselves to change, to improve the way we look at the creation all around us, both nature’s and man’s. This fall, may we heed the witness of David Franke, employing our eyes and minds to see more and more deeply — as Franke does and helps others to do through his art.

For more on David Franke’s abstract, conceptual and environmental mixed media works, visit Studio8e9.com.