Feature: Jens Jensen Returns to Door County

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

A huge crowd at an event in late August at the Baileys Harbor Town Hall saw Roger Kuhns go backstage with a tan suit over his arm. But the man who emerged wearing that suit a few minutes later looked and sounded nothing like Kuhns.

Who he did resemble to an uncanny degree was 86-year-old Jens Jensen – a bit stooped, with a bushy grey mustache, unruly white hair under a tan beret and a white silk scarf, fastened at the neck with a silver ring. He spoke for an hour in an accent that never faltered. The year was 1946, five years before Jensen’s death.

Jensen related that he first came to Door County, looking for a place in the country. His wife, Anne Marie, was beside him in their Model T; his secretary, Mertha Fulkerson, and the Jensen children were in the back.

“As we came up to Ellison Bay, this little town, for the first time, we got to the top of the hill,” Jensen said, “and do you know what I saw? Over the hill was the lake, Green Bay. There was a bluff with a forest on top. It looked just like my childhood home in Dybbøl, Denmark. I was so excited that I said ‘Anna,’ and I took my hands off the steering wheel and we drove into the ditch!”

Jensen backtracked a bit to explain that he was born in 1860 into a farm family. As a young man, he was conscripted into Kaiser Wilhelm’s Royal Guard and sent to Berlin, where he was fascinated with the beautiful parks – the inspiration for his career as a landscape architect.

Later he fell in love with a young woman who worked in his parents’ household. As the oldest son, he would have inherited the farm, but his father forbid his marriage to the “town girl,” so, in 1884, Jens and Anne immigrated to the United States, with 15 cents in Jens’ pocket.

Eventually, they settled in Chicago, where he found work as a street cleaner in parks that consisted of “mown grass, a single tree and a children’s wading pool in the hot sun” – nothing that would rejuvenate city dwellers “grinding away their lives in the mills and factories.” By 1905 he was general superintendent of the entire West Park System. In 1920, having designed four parks and a nature center with a waterfall and pond, he resigned from the park system and started his own landscape design practice focused on “bringing the wilderness back into the city.”

Among the renowned people with whom Jensen worked in “the Chicago Group” was Frank Lloyd Wright. “His mother was an expert in teaching the philosophy of Friedrich Froebel, who established the first kindergarten and believed that children should learn by using their own heads to build things with blocks – making something out of nothing. This is how he started as a child. Some of you have seen some of his buildings, and this is starting to make sense.”

“My wife didn’t like Wright’s designs,” Jensen said, “because the roofs always leaked. He was not an engineer, but he believed he was always right.”

Kuhns, as Jensen, then told the story about Herbert Johnson, head of the Johnson Wax Company in Racine, who was having a dinner party in the home Wright had designed for him when it began to rain and water from leaky windows dripped on his head. Furious, he yelled for a phone and called Wright, whose response was, “Move the chair.”

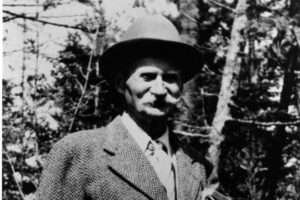

Jens Jensen

Anne Jensen died in 1934, and the following year Jens moved to Ellison Bay and founded The Clearing Folk School. Mertha Fulkerson, whom he had hired when she was 19, vowed she would not go because there was no plumbing and no running water. But she went and she stayed.

Among those whom Jensen admired were the poet Vachel Lindsay, conservationist Aldo Leopold and Door County artist Gerhard Miller. “As a child with polio, he endured incredible pain,” Jensen said. “Anyone who can go through that and paint such beautiful pictures has found himself. He taught at The Clearing for years, and when Gerhard and I got to arguing about philosophy, those students didn’t have a chance.”

But Jensen’s soul mate, the person who shared his deepest feelings about the spiritual power of nature and the need to protect and preserve it, was Emma Toft. “When she walks, it is like she is floating through the woods,” Jensen said. “As we walked at Toft Point, she said, ‘Mind where you put your foot. There is somebody living there.’ She respected nature, but there was a little bit of vinegar in her. If your ideas didn’t agree with hers, she would let you have it.

“She’d make those Swedish pancakes with chopped apples and nutmeg and butter, and I could stay there for a long time. And, oh boy, we’d talk about all sorts of ways that we would improve society.

“Many times when I traveled to Baileys Harbor,” Jensen continued, “I’d come over the backbone of Door County and I could see from Green Bay to Lake Michigan. There were no trees. Emma was determined to protect the forest her father had owned, but also the ridges near Baileys Harbor.”

It was Emma and Jens, of course, along with Olivia Traven and others who saved The Ridges Sanctuary from becoming a campground. “Some of us knew where mosquitoes are born,” Jensen said, “and thought the joke would be on them, when they were camping in the middle of a swamp. I can think of a few people who would go in there and the mosquitoes would be frustrated, because those captains of industry had no blood in them.”

“When Emma was very young, her boyfriend was killed in the war. One time I asked her, ‘So you don’t need a husband?’ And she said, ‘What man could ever fulfill me so much as this forest?’ Then she said, ‘Well, maybe you, Jens,’ and gave me the lightest kiss on my cheek, like a hummingbird had breezed by. You see, she has a higher purpose. If we all had a higher purpose, think what we could do.”

Jensen appeared courtesy of the Baileys Harbor Historical Society, The Clearing, Friends of Toft Point and The Ridges Sanctuary.