Historic Door County Summer Camps

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

Happy campers…Door County was full of them in the 1920s. Its forests, fields and bays reverberated with Reveille at dawn and Taps at dusk. From the Mabel Katherine Pearse modern dance camp on Washington Island to the rustic Adventure Island Camp off the shores of Ephraim to Camp Meenahga in Peninsula State Park, Door County summer camps were a beloved rite of passage for many youth from the Midwest and beyond.

A 1926 brochure beckoning young women to Camp Kewahdin on Chambers Island states, “The summer camp is thoroughly established as an effective supplement to the winter school. It provides wholesome romance and adventure, and promotes courtesy and good cheer. The joy of living in the open develops vigorous bodies, alert minds, and happy hearts.”

The establishment and popularity of camps in Door County in the 1920s reflected a trend in American culture. “Summer camp became an American institution in the aftermath of World War I,” writes Nancy Mykoff in Summer Camping in the United States. Parents who worried that their sons were being “emasculated by overcivilization” or that their daughters were ill prepared for the new opportunities available to women in the post-war world, turned to camp as an answer. “Summer camp was presented as a cure for these social dilemmas. Camp brochures pledged…to transform ‘physically and spiritually illiterate’ boys and girls into ‘able bodied’ and ‘morally upright’ American citizens.”

Alice Dyer, a parent from Chicago, rhapsodized over the transformative nature of camp in a letter she wrote to the director of Camp Meenahga. “Mr. Dyer and I feel very deeply indebted to you for what your Camp did for Esther and Alice…After eight short weeks, both girls came back to us looking so rosy and in such radiant spirits that we almost doubted their identity.”

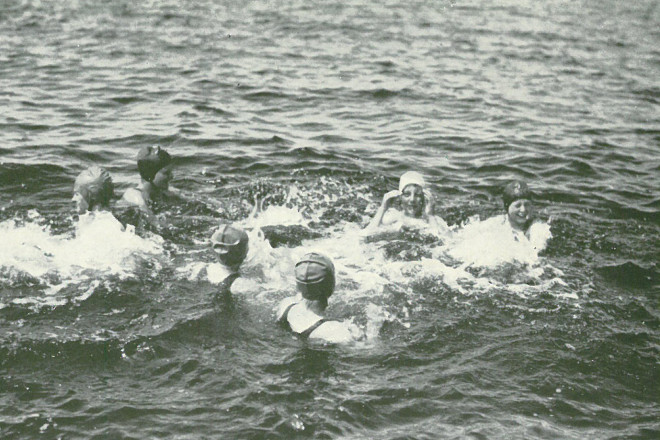

While the fresh air and sunshine they proffered might be free, summer camp wasn’t. With an average fee of $350 for an 8 to 10 week session (a $4,070 value today), camps catered to an affluent crowd. Elaborate brochures were printed and disseminated to attract upper class families, and camps competed with each other by offering a huge array of activities – swimming, diving, tennis, archery, drama, dance, horsemanship, sailing, canoeing, fishing, arts and crafts, nature study, overnight camping excursions, carpentry and more. Each camp augmented its regular activities with much-loved “Frolics” or “Red Letter Days,” events such as Popcorn Night, Cabaret, Supper at Eagle Bluff, Red Raspberry Picking, Derby Day, treasure hunts, minstrel shows, and formal teas with the directors. Outings into nearby villages were also a part of the fun and the Door County Advocate routinely made mention of the arrival of campers in Ephraim or Fish Creek, where they’d stop at Wilson’s for ice cream or the Maple Tree Café (now the Summertime) for pie.

In addition to physical and social activities, camps touted their wholesome food or “table” – fresh vegetables, milk, cream, butter and eggs. In some cases, meat and fresh fish were provided daily. Camp Kewahdin kept its own dairy herd, along with a herdsman from the University of Wisconsin to manage it. According to its brochure, “tons of the clearest ice” provided refrigeration, and the ice cream, “made at camp, is of the purest ingredients.”

Drinking water was pumped directly from the bay and analyzed by the State Board of Health. Camp  Kewahdin offered a Kewpie Lunch Club for underweight campers. In 1924 they reported, “the class as a whole made 650 per cent [sic] of the expected gain for their ages.”

Kewahdin offered a Kewpie Lunch Club for underweight campers. In 1924 they reported, “the class as a whole made 650 per cent [sic] of the expected gain for their ages.”

Along with good food, camps emphasized safety. Camp Meenahga in Peninsula State Park assured parents that in addition to a camp doctor, Sturgeon Bay’s physician and surgeon, Dr. Egeland, was just a phone call away and could “be at the camp within an hour.”

Campers were provided with an “Outfitters” list that included a camp uniform, in camp colors of course, and items such as “2 pair bloomers, 1 pair riding breeches, 6 middie blouses, 1 WARM sweater” etc. They were instructed to tag each item with a woven name label. Steamer trunks were shipped to Door County from all over the United States. Adventure Island Camp alone boasted campers from 36 states.

Because travel was time-consuming and expensive, campers typically journeyed on their own and stayed for “the season” – i.e. early June to late August. Many came by train. A Camp Meenahga Special Sleeper Train brought girls from St. Louis to Chicago, where Pullman cars were added to accommodate those who joined the group en route. After nine hours, the train arrived in Green Bay. Girls transferred to the Chicago and Northwestern line that ran a twice-daily route to Sturgeon Bay.

An alternative to the train was the steamship. An inexact schedule put the Goodrich Boat “touching at Fish Creek about July 6th.” Motoring was a third option. Campers heading to Chambers Island’s Camp Kewahdin were assured they’d get to Fish Creek on “splendid concrete and macadam roads through beautiful scenery.” Once there, they’d be transported on the Islander or As You Like It to the island. Certainly the prize for the most unusual mode of transportation went to the 19 boys and men who rowed a 36-foot homemade Viking replica boat 200 miles from Winnetka, Illinois, to Adventure Island in 1925.

Part of Door County’s allure as a camp destination was its near-perfect summer climate. Mabel Katherine Pearse relocated her eponymous camp from its first home on the mosquito-infested Lake Tomahawk to the northwest corner of Washington Island, where lake breezes apparently kept the pests at bay. Other aspects of Door County’s allure were its unique geography and remoteness.

Camp Panhellenic, on the northeast side of Washington Island, described its location as “isolated…in the extreme northern part of Lake Michigan.” Olga Achtenhagen’s poem published in the 1922 Lyre of Alpha Chi Omega celebrated the camp’s natural features.

“I can feel the cool lake breezes from the harbor blowin’ free

?I can hear the tent flap flappin’, and it’s there that I would be;?

Where the campin’ ground’s a-callin’, I can hear it callin’ me—

?To Wisconsin’s island forest, to Michigan’s blue sea.”

Although summer camps touted moral rectitude and rigorous schedules (“Reveille” at 7 am; breakfast at 7:30; flag raising ceremony at 8, tent cleaning at 8:30; general assembly and announcements at 9…and so forth, ‘til “Taps” brought the day to an end), they also promised autonomy and latitude.

With all the fresh air came a great amount of freedom – freedom from parents, the opposite sex and, even, from the person one was at home.

Camp Meenahga founder Alice Orr Clark starts out her letter to parents on a serious note – “We are trying to teach our girls to THINK…She must realize her responsibility, first to herself and then to others; what she must contribute, and what she must get out of this wonderful community life.” She closed the same note with an equally important entreaty: “Remember, this camping season is a vacation. Vacation means happiness. Happiness is everyone’s due.”

Camps are, by their very nature, fleeting. The camps that dotted Door County’s islands and peninsula in the early part of the last century offered a hiatus from life, an almost dreamlike experience for those fortunate enough to attend. As the 1920s turned into the 1930s, many of these cherished camps disappeared. A few endured into the 1940 and ’50s. Some closed due to the failing health of a founding director, others because state regulations required upgrades, such as indoor plumbing, that were too expensive to absorb. And certainly, most were affected by the Great Depression, which made camp a luxury fewer people could afford or justify.

Camps were fleeting in the impression they left on the land, too. Tents were dismantled and fire rings disappeared as quickly as a campfire’s embers faded. The foundation of a dining hall may remain here or there, if one knows where to look. In some instances, a lodge was turned into a private residence.

John and Patty Lehman own the property that once housed the Mabel Katherine Pearse Camp on Washington Island. He recalls visits from elderly women looking for traces of their camp and reminders of happy times. “But,” he notes, “that hasn’t happened for awhile now.”

In her farewell letter announcing the closing of Camp Meenahga after 33 years, Clark writes, “There is always a beginning and by that same token, an ending.”

The following are just some of the many camps that have called Door County home over the years. Others included Camp Careless in Idlewild and Camp Mudjeeke in Lily Bay, both near Sturgeon Bay; Camp Wildwood in Juddville; Camp Fish Creek, where Hidden Harbor condos are today; Camp Greenwood in Ellison Bay and Camp Shoreland in Jacksonport.

Mabel Katherine Pearse Camp

Location: Washington Island

Years operating: 1923 – 1940

Founder: Mabel Katherine Pearse

Campers: Girls 8 – 18 years old

In a January 2013 essay published in The Antioch Review, Marcia Cavell wrote “When I was ten I went for the first time to a place I came to love, a dance camp on Washington Island in Lake Michigan…Our Prospero on that island, always singing with the sound of gulls, and orioles, and mourning doves, was Mabel Katherine Pearse.” Mabel Katherine Pearse was a social reformer credited by some with introducing modern dance to Chicago. She was a “resident” at Jane Addams’s Hull House, a social settlement home for immigrants. Her resident duties included dance instruction. In 1923, she opened a camp that catered to approximately 28 mostly upper class dance students. It was the only one of its kind in the Midwest. Cavell wrote, “I loved Lake Michigan, where we bathed and swam alongside the huge water-snakes that…we came to feel were just an undulating, rather beautiful part of the water. I loved the rusted water pump where we drew water, and the gas lamps…and the little wooden cabins, built for only six girls each, in my case presided over by my dance teacher, Marge Turner…Above all I loved our classes in modern dance in the ivy-covered barn with the softly gleaming oak floor.”

Miss Pearse believed that through modern dance and techniques of relaxation, one could achieve the “complete freedom of the individual.” According to a 1934 article in Wilmette Life, “While a great deal of attention is paid to manners and regularity of habits (at the camp), organized routine and discipline are avoided as much as possible.” Cavell called it “an experience that informed my pursuit of happiness for a long time.”

Adventure Island Camp

Location: Big Strawberry Island, renamed Adventure Island

Years operating: 1925 – 1952

Founder: Charles A. Kinney, aka “Skipper”

Campers: Boys 7 – 14 years old

According to camper and counselor Don Oleson, Charles “Skipper” Kinney was an inveterate sailor and former shop teacher who created and ruled over a camp dedicated to “the spirit of adventure which is inherent in practically every boy.” Unlike many other camps, all the work on Adventure Island Camp, except cooking, was done by the boys – and it was done without electricity or running water. In the early years, this included building the camp’s cabins and other structures. In exchange for their hard labor, the boys were given a heady amount of freedom. Jerry Chomeau recalls, “He (Skipper) would let you do virtually anything you wanted to – in fact encouraged it – as long as it was reasonable. If you wanted to go out in the woods for the night, out by yourself, just take off.” The boys dug ponds and outfitted them with fish and frogs, built wooden kayaks, and took their Serpent of the Sea Viking ship on five-day “cruises” to places as far away as Escanaba or Marinette. If this wasn’t heavenly enough, the boys were allowed to bring their dogs for the summer. The camp’s freedom came with consequences, however. Campers were “free” not to do their dishes, but then they ate on dirty plates. They were “free” not to write letters home, but then they forfeited a ticket to Sunday’s special and highly anticipated dinner. As the camp became more established, it offered a baseball league, stamp club, journalism, orchestra and shooting range to augment the activities the boys created themselves.

Camp Kewahdin

Location: Chambers Island, Fish Creek

Years operating: 1922 – 1926

Founder: Mrs. E.J. Barrett

Campers: Girls 8 – 20 years old

Just across the water from Adventure Island Camp was an outfit offering a very different camping experience. Camp Kewahdin operated for only four or five seasons, but while it lasted, it was, according to H. Wellington Wack, a “camp of exceptional organization, equipment and individuality,” and he should know. Wack inspected more than 360 camps in his life and described them in The Camping Ideal. He was taken with the “western girls” who were “as bonnie a lot of lively young women as you’ll ever meet in this world…natural and eager, and always wood and water sprites of grace and charm and a bounding spirit.” Although he doesn’t mention it, he must have been equally impressed with the camp facilities, which included an electric light plant, sewerage system, steam laundry, warehouse and bakery. The camp advertised hot and cold running water and bathtubs. The camp’s elegant Main Lodge, complete with a library, assembly room, three dining rooms and servant quarters, overlooked inland Lake Muckasee (now spelled Mackaysee). The girls stayed in “artistic cabins…called Kiosks.” Each kiosk had electric lights, hardwood floors, shutters and screens.

Wack stated, “So far as we know, this Camp Kewahdin on Chambers Island is the largest private camp site in the United States.” And although it was more expensive than other camps in Door County, it attracted between 85 to 125 girls each season, partly from ads placed in magazines like Good Housekeeping.

Camp Kewahdin was created by Mrs. E. J. Barrett and her husband. Mrs. Barrett had inherited most of Chambers Island when her father, Fred Dennett, died in 1922. The luxury camp ultimately proved unsustainable and in 1926, Chambers Island, which had been in the Dennett family for more than two decades, was sold to a group of private investors from Chicago.

Camp Meenahga

Location: Peninsula State Park, Fish Creek

Years operating: 1916 – 1948

Founders: Alice Orr Clark and Fanny W. Mabley

Campers: Girls 8 – 19 years old

Camp Meenahga (the Ojibwa word for “the blueberries”) welcomed 80 to 90 girls each summer and gave them “a vacation from fashions and abnormal excitement.” Its location in Peninsula State Park provided a home base for excursions to Folda’s Island (now Horseshoe Island), where they were fed and entertained with tales of Native Americans by Mr. and Mrs. Folda. They rode horseback into Fish Creek and took overnight canoe trips along the shore, sometimes 50 miles or more, to Gills Rock and back. Elaine Mabley Schram, whose mother co-founded the camp, recalls “sleep-out nights” at Svens Tower or Eagle Tower and quips, “The sleep certainly was out!” She wrote, “I wonder if the atmosphere above Northern Wisconsin still permits the glorious displays of Aurora Borealis…When this happened after ‘lights out’ there was an unwritten agreement we could all go down to the pier, lie on our backs and watch the show with no penalties attached.” She also recalled the joys of swimming without suits in the waters of Green Bay. “We quaintly called this going in a la Venus, and how we loved the feel of it, sometimes in the path of moonlight on the water. In later years this had to stop because of the increasing number of ‘tourists’ whom, of course, we scorned.”

The Door County Democrat called Camp Meenahga “probably the merriest place on the whole Door County peninsula.”

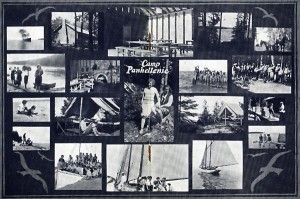

Camp Panhellenic

Location: Jackson Harbor, Washington Island

Years operating: 1919 – sometime in the 1930s

Founder: Gladys R. Dixon and Ruth Siefkin

Campers: College-age women

Camp Panhellenic was founded by Gladys R. Dixon, the director of physical education at Washington University, St. Louis, and her friend Ruth Siefkin of Wichita, Kansas. According to an article in a 1922 women’s fraternity magazine, the Arrow of Pi Beta Phi, “The venture is proving a boon to college women and alumnae as a place for rest and recreation as well as a place to promote a fine, broad, intercollegiate spirit.”

A 1921 ad in the Trident of Delta Delta Delta said that college women “who are vagabonds for the summer will find a woodsy goal, free from the conventional summer resort — where they can store away their company manners with their ‘store clothes’ and tarry in the Heart of Nature, reviving the old college spirit around the campfire.”

An article in a 1921 Key of Kappa Kappa Gamma told about the 1921 Pi Beta Phi Convention at Charlevoix, Michigan. A group of 40 Pi Phis traveled from the convention on boat to the camp for a two-week stay. After a week of hot weather, “Things got better for the group’s second week when ‘much sleep, splendid meals, and a cool breeze made us feel like living.’ When a local farmer called on the camp to save his cherry crop, there was unanimous response.” The group made 10 cents for each quart of cherries they picked and donated it to the Pi Beta Phi Settlement School in Gatlinburg, Tennessee.

Camp Panhellenic disappeared sometime after the 1920s. A stone chimney and fireplace were eventually incorporated into a private home and portions of the camp property are now protected by The Nature Conservancy.

Special thanks to Fran and Paul Burton, Cheryl Ganz, Mary Grota, John, Patty and Mary Pat Lehman, the Door County History Museum and the Door County Library’s Laurie History Room for information, camp brochures and images.

Sources:

Camp Meenahga, Alice Peddle, presented to the Door County Historical Society.

Door County’s Emerald Treasure, William H. Tishler. Madison, Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2006.

Door County’s Islands, Paul and Frances Burton. Ephraim, Wisconsin: Stonehill Publishing, 2009.

Old Peninsula Days, Hjalmar Rued Holand, Ephraim, Wisconsin: Pioneer Publishing Company, 1934.

The Camping Ideal, H. Wellington Wack, New York, New York: The Red Book Magazine, 1925.

Door Life issue date March 12, 1993.